Nessana

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

Excavations at Nessana in the Negev were resumed in 1987–1995 by an expedition of Ben-Gurion University, under the direction of D. Urman. In 1987–1991 the excavations were co-directed by J. Shereshevski, and in 1991–1992 by D. E. Groh.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

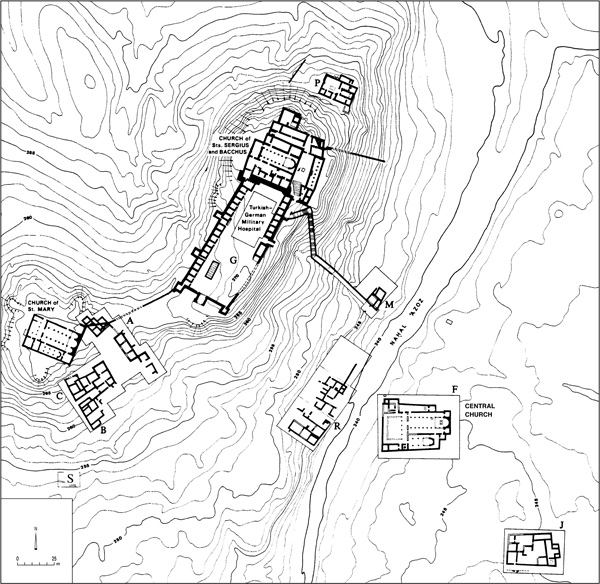

THE STAIRWAY (AREAS M AND M1). A stairway ascended to the northern peak of the upper town from the western bank of

The stairway remained in use in later periods and was incorporated into the Byzantine complex in the upper town, where a fort and the Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus were constructed. According to A. Negev, the stairway led to a Nabatean temple beneath the Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus, but no remains of such a temple have yet been found.

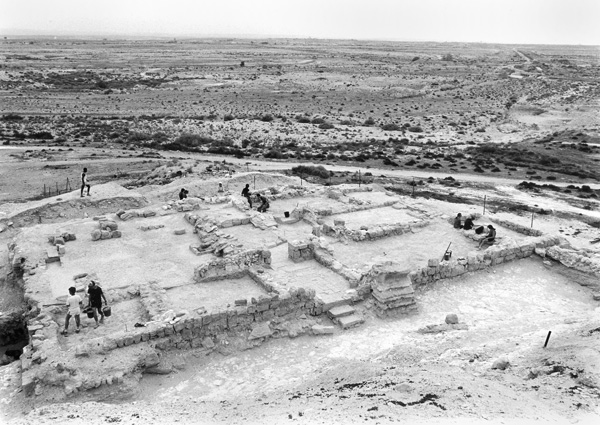

THE NORTHERN MONASTERY (AREA P). On the northern slope of the upper town of Nessana were uncovered the remains of a monastery that was dated to the last quarter of the sixth century CE. The monastery was not known prior to the Ben-Gurion University excavations. It is rectangular in shape (external dimensions 23 by 14.5 m), originally having consisted of two wings identical in size, one on the western side and the other on the eastern. The single entrance, in the southern wall of the monastery, led to a guard’s room (internal dimensions 3.2 by 2.45 m) paved with local stone. The guard’s room opened onto the courtyard (10.3 by 8.85 m), with a crude white mosaic floor surrounded by a frame of three bands of black tesserae. Set in the mosaic were four round medallions containing geometric motifs in orange, yellow, white, and black. Underneath the mosaic floor was a stone-built and plastered reservoir (2.7 by 1.8 m, 2.7 m deep) with a capacity of c. 17.5 cu m. A bench made of local stone was built against the northern wall of the courtyard. Two rooms south of the courtyard apparently served as the monks’ living quarters.

The eastern wing contained an entrance hall (narthex) that gave access to a chapel (7.6 by 3.3 m) abutted by two rooms to its north and south. The threshold and southern jamb of the entrance to the chapel were well preserved. A stone lintel decorated with a relief of a cross flanked by rosettes at its center was found nearby. It probably stood at the entrance to the chapel. In the eastern wall of the chapel were uncovered the foundations of the apse. Fragments of the offering table, altar, and a marble panel of the chancel screen were also found. Two fragmented glass goblets retrieved in the apse may have served as calyxes (sacramental cups). The roof was tiled, judging from the numerous finds.

The floor of the chapel was paved in limestone flagstones, the bema (2 m deep) in slabs of local hard limestone. Alongside it were three engraved crosses on the floor and beneath them was a rock-cut tomb with the remains of three men laid on a bed of Euphrates poplar leaves. One of the skeletons wore a pair of leather sandals with nailed soles. A grave containing the remains of a woman was uncovered under the stone floor in the room adjoining the chapel from the northwest. The function of the other rooms in the eastern wing could not be ascertained. Perhaps they were storerooms or service rooms. Three other rooms were later added to the monastery complex, two in the north and one in the south. The monastery was destroyed in the Early Islamic period and its rooms were turned into ordinary dwelling rooms.

The finds uncovered in the monastery include sherds of 21 pottery lamps from the late Byzantine period and the beginning of the Islamic period (end of the sixth and the seventh centuries

THE CHURCH OF STS. SERGIUS AND BACCHUS (AREA K). The Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus was extensively excavated by the Colt expedition, which referred to it as the North Church. A number of trenches were opened there in the recent Ben-Gurion University excavations. Beneath the church the Hellenistic-Nabatean foundation was uncovered, yielding two coins of Alexander Jannaeus (103–76 BCE). These Hasmonean coins join the unprovenanced coins of John Hyrcanus and Alexander Jannaeus reported by the Colt expedition. Judging from these finds, and other Hasmonean coins recovered at Nessana, it seems that the city was conquered by Alexander Jannaeus in approximately 100 BCE during his war in Gaza and the northern Negev. South of the Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus, in rooms identified as a martyrium by the Colt expedition, were found complete burials inside stone-built cist graves. Some of the dead had been buried in shrouds and leather sandals, fragments of which were preserved.

THE BYZANTINE FORT (AREA G). The Byzantine fort (internal dimensions c. 85 by 35 m) extended over a substantial area on the northern peak of the upper town. It had been briefly surveyed by the Colt expedition, which dated it to the time of Theodosius I (378–395

UPPER AREA A. In the southwestern part of the peak of the upper town, adjoining the Church of St. Mary, the well-preserved foundations of a residential building with six rooms were uncovered. The floors of the rooms were made of hardened crushed chalk. On the basis of the ceramic and glass finds, the construction of the building is dated to the middle of the eighth century CE. It remained in use until the middle of the ninth century

LOWER AREA A. The remains of another building, consisting of a row of three rooms, were uncovered in the recent excavations southeast of the Church of St. Mary. The ceilings had collapsed in the rooms; they were constructed of local limestone slabs laid in a criss-cross pattern on supporting arches. In room 1 were found sherds with scribal exercises written in ink, two large shells that probably served as ink wells, and remains of wooden furniture, some made of cedar of Lebanon. It may have been a study room or a scriptorium of the local scribes who wrote the papyri found in the Church of St. Mary. Remains of a leather sandal and bone implements were found in other rooms. From the fill beneath the floors were recovered sherds of Nabatean pottery, Eastern terra sigillata ware, and a city coin of Gaza from the time of Commodus (177–192

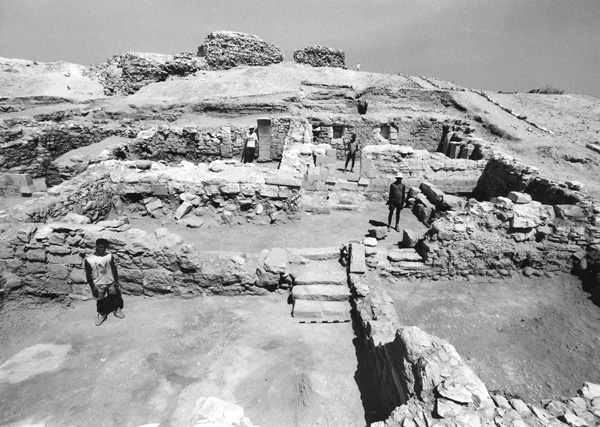

THE “PRIEST’S HOUSE” (AREA C). A large building of 12 rooms adjoins the Church of St. Mary. It was excavated in its entirety. The rooms were grouped into three separate living quarters. The building’s proximity to the Church of St. Mary, its carved ornaments, and crosses found on its doorways suggest that it may have served as the residence of the church’s priest and his assistants. The staircase in the courtyard probably led to a second story, which was also used for dwelling purposes.

The eastern wing consisted of a vestibule, an inner courtyard, a kitchen, and a triclinium. Two phases of occupation were identified, the first from the end of the sixth to the end of the seventh century CE and the second from the seventh–eighth centuries

The stones of the doorways of the building were decorated with geometric and floral patterns and crosses; a cross was painted on one of the doorjambs. The ceilings were built of stone slabs set in a criss-cross pattern and supported on arches. The walls were built of finely hewn ashlars of local limestone with a combination of dressed and undressed stones, their inner face plastered.

AREA B. Parts of a large residential building were uncovered southeast of the “Priest’s House.” Other residential buildings in this area are yet to be excavated. The building was constructed in the sixth century CE and remained in use until the beginning of the ninth century. It was constructed on two levels on a slope, its western wall about 25 m long and bordered on an unexcavated street or lane. Like the other residential buildings at Nessana, its rooms were roofed with stone slabs laid in a criss-cross pattern on arches. Some of the rooms were not roofed, and resembled inner courtyards. During the long period of the building’s use, it underwent internal architectural changes; doorways were blocked, and new floors were laid. Its rooms contained four floor levels, made of packed chalk or paved with local limestone slabs. In the inner courtyard were found a staircase leading to the second story and a stone-built cooking stove. Some of the stones of the entrance to the building were decorated with a dentil pattern; a lintel adorned with a cross in a circle was also found. Three small compartments along a wall, probably troughs, were uncovered in an area of the building. Only 10 of the building’s many rooms were excavated.

BUILDING COMPLEXES ON THE SLOPE (AREA R). Numerous floors and tops of walls were uncovered on the western bank of

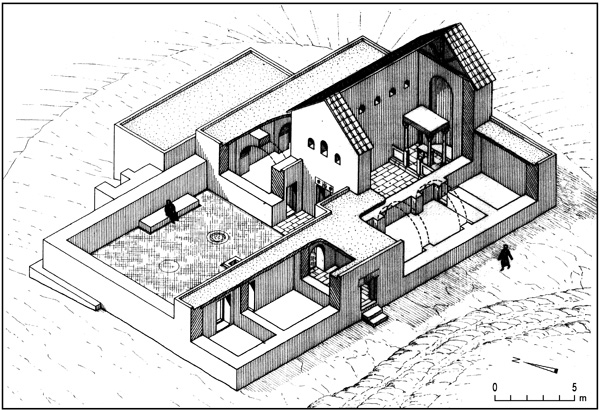

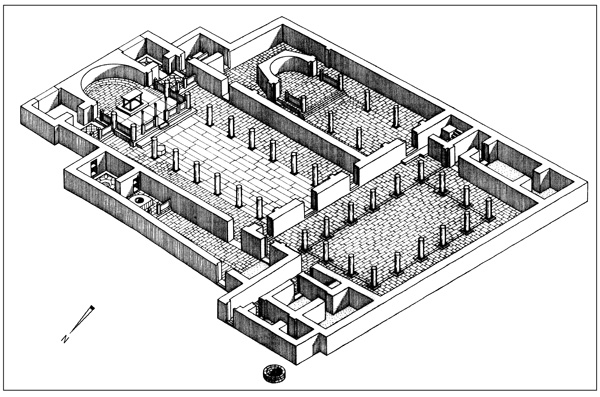

THE “CENTRAL” CHURCH (AREA F). At a distance of 55 m east of the bed of

The sanctuary included an apse flanked by pastophoria and a T-shaped bema. In the apse (5.9 m wide, 3.6 m deep) were depressions in the floor for the synthronon, which was made of cedar of Lebanon; its remains were recovered in the excavations. The northern prothesis (internal dimensions 4 by 3.1 m) was paved in a polychrome mosaic floor that was destroyed in the Ottoman period when a lime kiln was constructed above it. A colorful mosaic floor with a variety of intertwining geometric motifs was also found in the southern pastophorium (internal dimensions 3.35 by 3.1 m), and on the bema (3.4 by 2.8 m), which was in front of the pastophorium. Opposite the central bema (7.45 by 5.35 m) in the hall were found two fragments of chancel posts and pieces of the chancel panels made of fine marble and decorated with wreaths and crosses. In the center of the main bema was found the base of the altar (2.4 by 1.8 m), also faced with marble panels. Fragments of the marble altar table were found scattered on the bema, which was enclosed by a chancel screen. One of the two bases of the ambo was also recovered.

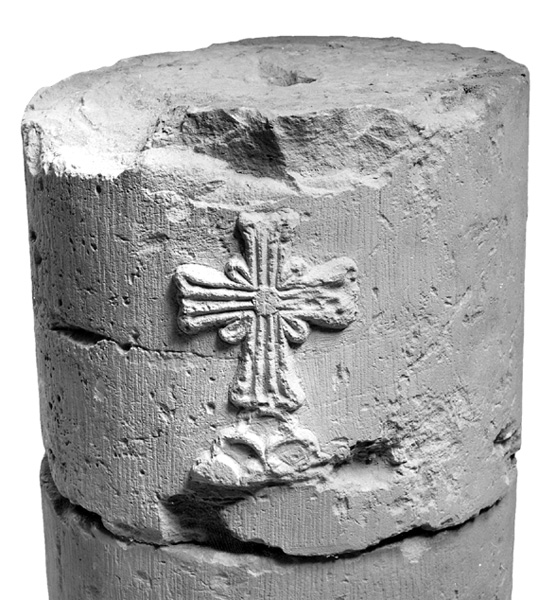

The church hall (internal dimensions 23.5 by 14.35 m) was divided into a nave and two aisles by two rows of eight columns, which supported the wooden ceiling. The nave was paved with marble slabs. On the bottom of several of these marble slabs were inscriptions in Greek in reddish-brown ink of the names of the masons. The top of the marble slabs bore Arabic inscriptions in black ink of verses from the Koran, prayers, and oaths; they date to the end of the eighth or beginning of the ninth century and represent the church’s latest phase. The aisles were paved with hard local limestone, plundered for use in the construction of later buildings. The 16 columns supporting the church’s tile roof were made of drums of the local hard limestone. On the four central columns in the nave were found stylized crosses and leaves. One of the columns bore the Greek words “light and life” within a cross symbolizing Christ. The finds in the church include fragments of lintels, capitals, and bases of local stone, decorated in various types of relief, mainly stylized crosses and leaves, bunches of grapes, peacocks and other birds, and amphorae.

The baptistery adjoined the northern aisle of the hall. It included a chapel and auxiliary room. The baptismal font was located on the bema in the chapel, which was 18.8 m long, 3.8 m wide on the east side, and 5 m wide on the west (external dimensions). The floor of the chapel on the east side and in the center was paved with well-dressed local stones; in the west it was paved in a mosaic, of which only the bed has survived. The chapel’s bema (4 by 3.8 m) also displayed a fine pavement of slabs of local stone. Parts of the marble chancel screen posts and panels that stood in front of the western side of the bema were uncovered; they were also decorated with crosses and wreaths. The original baptismal font was semicircular and faced with marble panels. In its second phase, a monolithic round stone font was inserted into a stone and cement base (external diameter 0.85 m; internal diameter 0.64 m). East of the baptismal font was an annex, its floor paved with a colorful mosaic of intertwining geometric patterns and a central octagonal medallion containing a small cross.

The southern chapel flanked the church’s main hall and was divided by two rows of three columns into a nave and two aisles. It was 20 m long, 10 m wide on the west, and 9.3 m wide on the east (internal dimensions). Its floor was paved with slabs of hard limestone. The columns in the southern chapel were similar in construction and decoration to those of the church’s main hall. On the bema (4.9 by 4 m) in the chapel was a paving stone decorated with a cross and rosette; beneath it was perhaps a cavity for a reliquary. On the base of the marble altar table was a Greek inscription mentioning one of the donors, “Gadimo,” and the bishop “Victor.” The bema was enclosed by a chancel screen of marble panels decorated with wreaths and crosses. Along the apse (3.5 m wide and 2.25 m deep) was a corridor-like space that served as an ambulatory. A passageway led from the chapel to an auxiliary room, in which—judging from the finds— the gifts dedicated to the church were kept.

The courtyard (21 by 15.6 m) of the church consisted of an atrium surrounded by porticoes with tiled roofs. It was badly damaged by construction in the Ottoman and British Mandate periods. The six-columned eastern portico, 21 m long and 3 m wide, served as a narthex for the main hall and southern chapel. The narthex and courtyard were both paved in local limestone slabs. North and south of the courtyard were uncovered the foundations of ten auxiliary rooms with staircases leading to second-story rooms or roofs. Outside the church wall, in the northwestern corner, was a blocked well, 1.4 m in diameter.

THE STATELY HOUSE (AREA J). A stately house was uncovered roughly 100 m southeast of the central church compound. Eight of its rooms were excavated. It dates to the late Byzantine–Early Islamic period, from the sixth to the eighth centuries. The walls of the building were covered with a fine plaster decorated with floral motifs in a wide variety of colors.

THE AGRICULTURAL PERIPHERY. Two farms irrigated by run-off water were excavated at Nessana. The first, the Oded farm, is situated in the bed of a wadi between two hills, its roughly 4 a. surrounded by a 1-m-wide stone wall. Inside the walled area, eight terraces were preserved along the width of the wadi bed. The terraces were built of local stone and loess soil and formed seven variously sized fields; the difference in height between the highest and lowest terrace was 6.4 m. Rainwater was conveyed from the hills via low diversion walls and stone-built and rock-cut channels. Excess floodwater was moved from one field to another through openings in a flood chute built across the width of the terraces. The entire irrigation system supplying the Oded farm required an excellent knowledge of engineering and hydrology. Trial trenches dug in the terraces, walls, channels, and flood chutes uncovered only a meager amount of pottery dated from the Byzantine period to modern times.

The second farm, the Almond farm, was also built in the bed of a dry stream between two hills and surrounded by a 1-m-wide stone wall. In an area of c. 4 a. were eight well-preserved terraces that formed seven fields, the widest 70 m and the narrowest 55 m. As at the Oded farm, run-off water was diverted to the farm and fields from the wadi bed and the surrounding hills. In addition, two areas outside the farm were found covered with small mounds of stones cleared from the ground surface, aimed at increasing the flow of the run-off water into diversion channels leading to the fields. In trial trenches dug in the fields, Byzantine and Early Islamic period pottery was uncovered. In both farms were found modern remains that belonged to the local Bedouin who lived at the site.

The Almond farm’s small farmhouse (external dimensions 6.13 by 5.45 m), located to its north, was built of local limestone extracted from a small nearby quarry. It was entered through a doorway in the southern wall. The ceiling was made of limestone slabs supported by two arches, the floor of hardened limestone. The house stood in a large open yard (135 by 90 m) enclosed by a stone fence; in the yard were stone fences and various installations. The yard measured 3 a. and was approximately the same size as the agricultural area. Part of it may have been used for growing crops. Trial trenches inside and outside the house yielded pottery and glassware from the second half of the fifth to the eighth centuries CE.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Nessana was probably first settled as early as the third century BCE. Evidence for this date is provided by the assemblage of oil lamps typical of that period and a coin of Ptolemy IV from 212 BCE uncovered by the Colt expedition in the Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus in the upper town (area K). It is not clear whether the earliest inhabitants were Egyptians or Nabateans.

In the second century BCE, a fort was built on the northern peak of the upper town. The fort, with round towers and an internal area of c. 27 by 26 m, may have been built by the Nabateans. It certainly was used by them, their presence in the second century BCE attested by Nabatean pottery. The same type of pottery was also found by the Ben-Gurion University expedition in the latest excavations in both the upper and the lower towns. The second-century BCE Nabatean settlement at Nessana was probably conquered by Alexander Jannaeus in about 100 BCE. Evidence to support this date is provided by coins of Jannaeus found in several levels of area K on the northern peak of the upper town, in area R at the foot of the slope of the upper town, and in buildings beneath the courtyard and the “Central” Church compound in the lower town (area F).

After the Roman conquest of the region in 63 BCE, Nessana returned to Nabatean control. During the reign of the Nabatean king Aretas IV (9 BCE–40

A change in the trade routes in the area, which occurred after the Nabatean kingdom was annexed to the Roman Empire in 106 CE, marks the beginning of a period of decline at Nessana. There is no evidence of new construction at the site during the second–fourth centuries CE, and material finds from those centuries consist of only a few sherds and coins. The Byzantine fort (area G) south of the early fort located at the top of the northern peak of the upper town was constructed during the reign of Theodosius I (378–395). It reflects a renewed period of growth in the history of the settlement. Opinions differ as to whether the fort was occupied by the “very loyal Theodosians” dromedary unit mentioned in one of the papyrus fragments found by the Colt expedition, or by another Byzantine militia unit, as claimed by A. Negev. According to the papyri, the members of the unit seem to have been well received by the local population and in the course of time even cultivated the farms in Nessana’s agricultural periphery with their families.

A short while after the Byzantine fort was erected, construction of the Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus compound (area K) began above the ruins of the early fort. The complex possibly served as a monastery, as is suggested by some of the papyri found in one of its rooms. The introduction of Christianity to Nessana, which paralleled the construction of the new fort at the site, accelerated growth in both the upper and lower towns, parts of which were uncovered in the new excavations (areas B in the upper and R in the lower town). Christian settlement at the site peaked in the last quarter of the sixth century and during the seventh century CE. During the reign of Tiberius II (578–582), a new small monastery (area P) was built north of the Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus complex. In 601, during the reign of Mauricius (582–602), the Church of St. Mary was built on the southwestern peak of the upper town. In the same year a new baptistery was added to the Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus. It is possible that this wave of new construction is related to the conversion to Christianity of Arab tribes that recently had arrived to the area. A consecration inscription of uncertain provenance at Nessana, dated September 18, 605 and first published by H. Haensler in 1916, indicates that another church building was either renovated or newly constructed at the site at that time. This inscription may possibly refer to the remains of the church observed by investigators and travelers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries on the southern boundary of the lower town, its exact location unknown today.

Settlement at the site reached its highest point in the seventh century CE. The Muslim conquest of the area apparently did not harm Nessana’s Christian population. On the contrary, the largest church discovered at the site—the “Central” Church in the lower town (area F)—was built in the late seventh or early eighth century. It continued to function without interruption during the eighth century, and only at the end of that century, or early in the ninth century, did it pass into Muslim hands. Incidentally, there is no clear indication of a violent Muslim conquest of Nessana during the seventh and eighth centuries. While it is true that some of the residential buildings uncovered in the new excavations contained evidence of structural changes dated to those centuries, such as blocked doorways and the construction of new floor levels (in areas B, C, and R), it has not yet been determined whether these changes were a consequence of earthquakes in the region or were motivated by other circumstances. Nevertheless, the copious amounts of sherds and glass fragments, including luxury items recovered from these houses, clearly indicate that the economic status of Nessana’s population remained stable under Muslim rule.

With the fall of the Umayyad dynasty and the rise to power of the Abbasid dynasty in the mid-eighth century, a dramatic change took place at Nessana. It was apparently around that time that the monasteries on the northern peak of the upper town (areas K and P), as well as the Byzantine fort (area G), were razed. The Church of St. Mary on the southwestern peak suffered a similar fate. In the mid-eighth century, a new private house (upper area A) was built against the northeastern corner of St. Mary’s Church, on top of the ruins of the defensive wall that had formerly connected the Byzantine fort with the church. Distinguished among the ruins of the small monastery in area P and the private house in area B were renovations from the second half of the eighth century and perhaps even the first half of the ninth century. The renovations reused Byzantine architectural elements.

DAN URMAN

RENEWED EXCAVATIONS

Excavations at Nessana in the Negev were resumed in 1987–1995 by an expedition of Ben-Gurion University, under the direction of D. Urman. In 1987–1991 the excavations were co-directed by J. Shereshevski, and in 1991–1992 by D. E. Groh.