Ramla

EXCAVATIONS

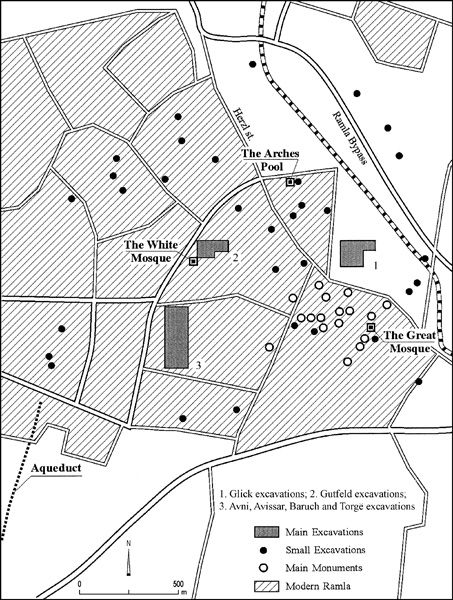

In the wake of development and construction projects, 79 salvage excavations and soundings were conducted in various parts of the city of Ramla in 1990–2003. While most of the excavations were probes at building sites or under modern streets, a number of large-scale excavations were also carried out in areas north and west of the Old City and north and south of the White Mosque. Several excavations were also conducted around the Ramla bypass road northeast of the Old City and in the western suburbs of the modern city. The aqueduct that carried water to the city from the springs at Tel Gezer was also examined in salvage excavations. Although they were conducted in non-contiguous areas, the many excavations make it possible to arrive at a tentative reconstruction of Ramla in the Early Islamic, Mameluke, and Ottoman periods. In addition to the excavations, an architectural survey of the buildings from the Middle Ages and the Ottoman period was conducted by A. D. Petersen in the center of the city.

THE COURTHOUSE COMPLEX

In 1994–1995, an area of about 5 a. was excavated by D. Glick on behalf the Israel Antiquities Authority at the site of the new Ramla courthouse. Ten excavation areas were opened, revealing houses, subterranean installations, and cisterns. The evidence attests to continuous occupation through the Early Islamic period. Two inscriptions in Arabic were found dated to the first quarter of the tenth century. Also found were the remains of an olive-oil press and a mosaic pavement with geometric motifs intertwined with figures of animals—birds, what appear to be donkeys eating dates from a tree, and a tiger—all on a white background. In another area, two underground silos were uncovered: one, 8 by 4 m and 4 m deep; the other, 12.6 by 4.6 m and 3.6 m deep. The outer walls of the silos were constructed of fieldstones bonded with mortar and the inner walls were plastered. Their roofs were probably built of barrel vaults. In the southern part of the site were two rectangular pools; one contained traces of red paint and may be the remains of a dyeing industry. Around the pools were remnants of drainage channels, sewage systems, and cisterns.

Thirteen cisterns were uncovered in different parts of the excavations, some close together (only 3 or 4 m apart). A ramified system of channels that drained runoff water from the roofs of the nearby houses led into the cisterns. A number of cesspools constructed with vaults of fieldstones were built directly on the sand dunes. In the middle of a plastered courtyard in another spot, a well (2 m in diameter, 6.7 m deep) had been dug down to groundwater, its mouth of ashlar masonry.

In 1997, F. Vitto investigated an area east of the above excavations that contained plastered pools, a cistern, and drainage channels from the Early Islamic period, and remains of buildings with plastered floors from the Mameluke period.

THE AREA NORTH OF THE WHITE MOSQUE

In 1996, excavations were conducted by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem under the direction of O. Gutfeld in several areas north of the White Mosque (areas 81.1, 81.2, and 82.1) and in two areas north of the Old City, near the Ramla police station (area 62.1) and on Marcus Street.

In the northern part of area 81.1, part of a drainage channel (0.50–0.70 m wide, 1.6 m high) dating from the Abbasid period was exposed. It was probably part of the municipal drainage system. The travertine residue in the channel attests to the large quantity of water that flowed through the channel. In the southern part of the area, robbers’ trenches and a number of plaster floors cut by the trenches were observed. The stones of the walls were probably looted in the Late Islamic period.

The main architectural features uncovered in area 81.2 were the foundations of a massive wall and two plastered floors dating to the Umayyad period. An installation containing a large amount of iron slag, discovered in the northern part of the area, may have belonged to a metal industry from the Abbasid period.

Area 82.1 is situated near the northern part of the White Mosque. Its southern part contained impressive remains of a large structure dating to the Umayyad period. One of the squares yielded two large ashlars overlying a fieldstone foundation; the other ashlars had apparently been looted in the Late Islamic period. The northern part of the area probably suffered the same fate and consequently yielded no architectural remains.

Area 62.1 (the police station parking lot), 85 by 50 m, is marked by a slightly sloping terrain that drops in height from about 90 cm from east to west. The ten squares excavated yielded material dating from the Umayyad to Fatimid periods (strata V–III). The buildings and installations provided evidence of the existence of a metallurgical industry during the Early and Middle Islamic periods. The remains included well-built water channels and smelting ovens and the debris contained large quantities of metal production waste. The area was apparently destroyed and abandoned as a result of the earthquake of 1033, or, perhaps, the earthquake of 1068. The absence of finds from the Crusader period corroborates this assumption. Subsequently, during the Mameluke period, the area was robbed of its masonry, as is evidenced by the many robbers’ trenches dug along the earlier walls.

Remains of the Early Islamic period were exposed during the laying of a water pipe over a distance of about 65 m beneath Marcus Street. Water installations—pipes, channels, and cisterns—were uncovered beneath the eastern side of the street; on the western side, remains of walls and plaster floors of dwellings were discovered.

The foundations of the walls uncovered in areas 81.2 and 82.1 are composed of two rows of large fieldstones, measuring 1 m in width and bonded with hard gray mortar. The top of the foundations was also leveled with mortar to facilitate the laying of the ashlars above them. The few walls preserved in the area north of the White Mosque were 80 cm wide and similarly constructed of two rows of stones—ashlars on the outer face and more roughly dressed stones on the inner, the space between them filled with small fieldstones and mortar. In area 62.1, the walls consisted of one row of ashlars with gray mortar bonding on one side only. Most of the other walls had been completely dismantled and could be identified only by robbers’ trenches that were filled with soil containing dark gray ash, small stones, and sherds. In many cases, the trenches extended from surface level down to the virgin sand, destroying walls, installations, and water channels.

In the Early Islamic period, the plaster floors were laid directly on a roughly leveled surface of virgin sand. These floors were found damaged and uneven, apparently a result of ground movement during earthquakes. The water channels, varying in width from 50 to 70 cm, are coated with thick ash lime (hydraulic) plaster and their side walls are built of small fieldstones bonded with gray mortar. Several channels were covered with flat limestone slabs, bonded with gray mortar. Like the floors, the earliest channels were laid directly on the virgin sand.

The subterranean cisterns were bell-shaped and constructed of walls, 40 cm wide, made of small fieldstones bonded with mud and coated with a thick layer of gray hydraulic plaster. Alongside them were various installations including small settling basins of gutters plastered like the cisterns and connected to them by means of water channels or clay pipes. In several cases, two successive pipe segments were separated by a bag-shaped jar encased in gray mortar, into which the pipes were inserted.

THE AREA SOUTH OF THE WHITE MOSQUE

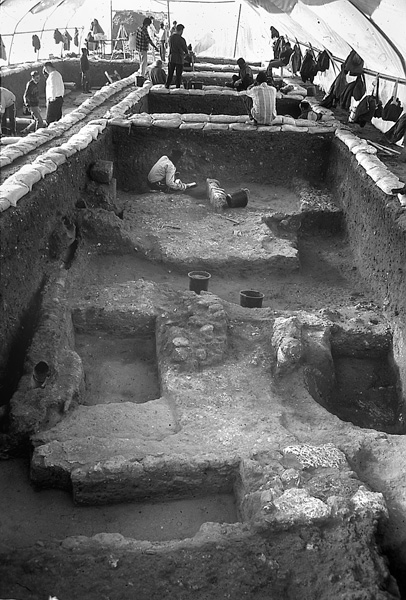

In 2002–2003, excavations were conducted on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority by G. Avni, M. Avissar, Y. Baruch, and H. Torgë in a large area (c. 500 by 300 m) south of the White Mosque and west of Ramla’s municipal stadium. Exposed in five main excavation areas, totaling c. 4,400 sq m, were remains reflecting uninterrupted urban development beginning in the Umayyad period (eighth century), and continuing through the Abbasid (eighth–ninth centuries) and Fatimid periods (tenth–eleventh centuries).

All the excavated areas yielded remains of an urban network of dwellings, some luxurious, as well as industrial installations, cisterns, and water channels. Alongside densely built residential neighborhoods were areas void of building remains but overlaid by fills containing a large amount of sherds. In none of the extensive excavation area was evidence found of occupation of the city after the middle of the eleventh century. The area was undoubtedly abandoned following the earthquakes of 1033 and 1068 and remained deserted until modern times. After its abandonment, the city was systematically robbed of its building stones. The course of the walls could be ascertained only by tracing robbers’ trenches.

AREA C. The largest continuous area excavated is located in areas C1–C4, about 80 m south of the White Mosque complex. Massive building remains were uncovered in an area of 65 by 55 m, which included private houses as well as public buildings. Three main building phases were distinguished in this location.

The earliest phase, dated to the eighth–ninth centuries, consists of parts of a large structure with a spacious hall (20 by 8 m), oriented north–south, paved in a polychrome mosaic bearing floral and geometric designs. Only a small fragment of this mosaic has survived; in most of the hall only the mosaic bedding was preserved. Several segments of the mosaic were repaired and covered with layers of plaster, evidence of the building’s long period of use. The hall was enclosed on the east and west by walls of dressed limestone, 0.7–0.8 m wide (only a few stones were preserved in situ). Smaller rooms, possibly living quarters situated north and south of the hall, were only partially preserved due to damage caused by later building activities.

Above this large building were the remains of small ninth-century dwellings containing various installations and cisterns. On the eastern side of the area were fragmentary remains of a small building with a central courtyard and cistern, surrounded by small square rooms. North of the building were a number of installations and rectangular pits that probably served as cesspits.

The latest phase in areas C1–C4 is represented by the remains of a large public building from the Fatimid period (tenth–eleventh centuries), consisting of a number of inner courtyards surrounded by dwelling rooms, extending over most of the excavated area and beyond it to the north. A somewhat crude polychrome mosaic pavement of large tesserae, bearing floral motifs on its southern side, was laid in one of the courtyards. Between the rooms and the courtyards were a number of cisterns, small pools, and water channels.

In the southern part of the excavated area (area C6), a large building uncovered from the Fatimid period was furnished with a water system that included pipes, channels, pools, and apparently an ornamental fountain. A segment of one of the walls (c. 15 m long) of the building, which was constructed on a north–south axis, was preserved to a height of about 1.5 m. Its outer face was built of ashlars; its inner face of fieldstones coated in plaster with a herringbone pattern. Five square rooms uncovered in the excavated area were built against the wall. The building’s entrance was to the south, where the eastern doorjamb of the well-built doorway was uncovered. Its floor, made of flat square bricks, was preserved only in small sections in one room. Beneath the floor was a plastered stone channel covered with bricks. Part of a courtyard exposed north of the building contained sections of a water system, including pools with red-plastered floors and channels. An ornamental fountain fed by clay pipes likely stood in the middle of an octagonal pool in the center of the courtyard. The floors of the pools in the building were covered in red plaster. The building was apparently destroyed in its entirety in an earthquake in the eleventh century. Two rectangular installations uncovered above it from the Mameluke period appear to be the only remains in the excavated area postdating that century.

AREA D. To the west is an uninterrupted area (area D), 30 by 20 m, the direct extension of another area to its west that was excavated by H. Torge in 2001. A group of buildings from the Fatimid period exposed in the area consisted of square rooms built around central courtyards. The walls were aligned on a north–south axis, with a slight deviation to the west. A large dwelling on the northern side of the area also consisted of rooms grouped around a courtyard. Its stones had been completely dismantled and the course of its walls could be reconstructed only by tracing robbers’ trenches. In the courtyard a large cistern with a dome-like top was fed by several channels. In one of the rooms of the house, traces of plaster with blue-painted decorations were found on the walls. The floor was carefully plastered. The residence was apparently built alongside another dwelling that extended southward outside the limits of the excavation area. The method of construction of the walls is noteworthy: a foundation trench was dug into the ground then filled with sand, and the foundations of the house were subsequently laid within the sand fill.

AREA E. Excavations in a 35-by-15-m area in the southwestern part of the excavation area exposed scattered remains from the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, and parts of a large building from the Fatimid period. The foundations of its walls, some installations dug into the ground, and a segment of a colorful mosaic pavement with geometric motifs survived. In the center of the building was a rectangular courtyard or entryway with a white tessellated pavement and a polychrome mosaic carpet at its center, probably opposite the building’s entrance. The mosaic was decorated with a geometric design consisting of two intertwining squares; at its center was a bowl and floral motif depicted within a frame. Little has survived of the building’s living quarters. South of the courtyard (or entryway) were parts of square rooms with plastered floors. North of the building was a cistern with a dome-shaped top fed by a number of channels. This area apparently contained an outer courtyard connecting the building with an additional building extending to the north, of which only sections of walls and installations were preserved.

AREA A. In the southeastern part of the excavation area, four sub-areas were excavated (areas A1–A4), each measuring about 10–15 by 15 m. In all of these areas houses from the Fatimid period were constructed above poorer remains of the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. The southernmost is area A1, where part of a large structure with two distinct building phases was uncovered. The early phase dates from the eighth and ninth centuries and consists of two square rooms with fieldstone walls and plaster floors. The inner faces of the walls were meticulously plastered. On the floor of the eastern room was a round pit whose function is not clear; in another room a large storage jar was sunk into the floor. In the Fatimid period, a larger structure was built above this building and some of its walls were incorporated into walls of the earlier building. Only part of the structure was excavated, but it appears to have consisted of a row of rooms facing an open courtyard with a large cistern on their eastern side. The floors, about 0.7 m higher than the floors of the earlier building, were carefully plastered, as was the inner face of the walls, segments of which were preserved to a height of about 0.5 m.

To the north, in areas A2 and A3, were the remains of installations and brick walls from the eighth and ninth centuries, above which were walls of the Fatimid period. In area A4, also to the north, a cistern was excavated in its entirety. On its base lay a deposit of building stones, some ashlars, and a number of voussoirs.

AREA B. Two large areas, each 15 by 10 m, were excavated in the northern and eastern parts of the excavation area. In the northern (area B3), located about 50 m from the White Mosque, a section of a large building was uncovered that was apparently constructed in the eighth century. The walls, laid directly on the sand, were built of massive ashlars and preserved in parts to a height of three courses. A large ashlar pier at the end of one of the walls may have belonged to a gate. Beneath the building’s floor, which was made of crushed chalk, was a vaulted chamber (about 2.5 by 1.5 m) built of dressed stones that may have served as a cellar or cesspool. In the Abbasid period, it was turned into a refuse pit and contained masses of pottery and glassware from the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, including vessels with inscriptions in Arabic. There were also a number of glass vessels of the luster glass type decorated with floral and faunal motifs, some bearing Arabic inscriptions. The richness of the finds implies they came from mansions or even a palace.

AREA F. In the eastern area, opened in the area of the municipal stadium (area F1), a large building was uncovered at surface level, of which only fragmentary walls and floors had survived. A large square room (about 5 by 5 m) and some smaller rooms were found paved with a white mosaic and marble blocks. West of the building was a cistern that was probably in the center of an open courtyard and fed by a network of channels and pipes. The building apparently dates to the Abbasid period; the material in the fill of the cistern suggests that it remained in use during the Fatimid period.

RAMLA EXCAVATIONS: A SUMMARY

The numerous excavations conducted in Ramla in recent years, all the result of construction projects, have greatly increased our knowledge of the size of the city and its development in the Early Islamic period. The city underwent significant growth, mainly in the Abbasid and Fatimid periods, and reached its maximum extent in the eleventh century, but was destroyed and abandoned in the two devastating earthquakes of 1033 and 1068. Following its destruction, the northern, western, and southern parts of the city were never resettled, the stones from their ruined buildings reused in the construction of the Crusader and Mameluke city, which was apparently smaller than the Early Islamic city and concentrated mainly in the center of the modern city.

The fragmentary architectural remains from Ramla, most of private dwellings, are consistently oriented north–south, with a slight westward deviation. This pattern is evident in the results of large-scale excavations south of the White Mosque, as well as in excavations conducted in other parts of the city. Thus, an orthogonal plan appears to have been the dominant feature in Ramla’s urban layout.

The first important construction within the limits of the city is ascribed to the Umayyad period, when at least two structures were erected north of the White Mosque. Open spaces around the buildings served as gardens or fields. In the excavations south of the White Mosque several houses from the Abbasid period were uncovered, at least one of which contained a number of polychrome mosaic pavements alongside many industrial installations and cisterns. There was no evidence of high-density construction over a large area.

Ramla reached the zenith of its urban life in the tenth–eleventh centuries. All the excavations conducted in the city revealed remains from this period, including residential buildings, industrial installations, and an extensive water supply system. Excavations south of the White Mosque uncovered a dense network of houses alongside industrial workshops and cisterns. In two of the houses were polychrome mosaic pavements.

Many of the excavated areas provided evidence of intensive industrial activity, represented mainly by plastered installations with remains of dye and small collecting pools for various liquids. The numerous installations, water channels, and cisterns attest that area 62.1, north of the White Tower, was an industrial zone. The analysis of the refuse in the ovens in this area indicates that several of the installations were used in the production of metals and iron.

Tremendous effort was spent in developing public and private systems of water supply and collection in the city, beginning with the aqueduct that brought water from springs in the Gezer area (see below), through the ramified system of cisterns and channels for conveying water, and finally the clay pipes that drained water into the houses and rainwater into the many cisterns in the homes. Found in area 81.1 north of the White Mosque was one of Ramla’s main water channels (from the Abbasid period), which conveyed water from the area of the White Mosque to the Arches Pool.

GIDEON AVNI, OREN GUTFELD

THE RAMLA AQUEDUCT

The Umayyad aqueduct to Ramla is referred to as Qanat Bint el-Kafir (“The Heretic Daughter’s Aqueduct”) on the map of the British Survey of Palestine of 1882; the source of this name is unknown. In 1950, R. Gophna and J. Kaplan mapped a section of the aqueduct at Moshav

Most of the course of the c. 10-km-long aqueduct can be reconstructed, but its water source and point of entry to Ramla have not yet been ascertained. Its source should probably be identified with the group of springs located in the vicinity of Abu Shusha, near Gezer. From there it runs northwest, entering Ramla from the south or southwest.

The aqueduct consists of a foundation of fieldstones bonded with cement and two parallel walls of dressed limestone masonry. The walls (40–50 cm wide) are plastered on their inner and outer faces and overlaid with another layer of fieldstones mixed with gray cement. The overall width of the aqueduct is about 1.5 m. Its channel is covered with flat limestone slabs averaging 30 by 80 cm and 12–15 cm thick, laid widthwise. The inside of the aqueduct was covered with an approximately 1-cm-thick layer of light red plaster composed of quartz, sherds, and shells applied to a base of sherds. Another layer of plaster was applied above this, somewhat altering the cross-section of the channel (specus), which varies along its length. In the eastern part of the aqueduct its width was distorted by the movement and inward collapse of the supporting walls and this section is at present completely blocked. Soundings made in the middle of the aqueduct revealed that it was dug into the virgin

In the middle of the excavated segment of the aqueduct is a cylindrical-shaped manhole, 1.30 m in diameter and preserved to a height of 0.50 m above the level of the cover stones. The superstructure is hollow and has a hexagonal internal horizontal cross-section (0.70 m in diameter). The manhole was built above a square opening set between the cover stones and is large enough for a person to enter. A similar manhole was exposed 45 m to the west, but its superstructure had collapsed. No cover stones were found in situ in the westernmost part of the exposed segment, probably having been robbed in antiquity.

AMIR GORZALCZANI

Color Plates

EXCAVATIONS

In the wake of development and construction projects, 79 salvage excavations and soundings were conducted in various parts of the city of Ramla in 1990–2003. While most of the excavations were probes at building sites or under modern streets, a number of large-scale excavations were also carried out in areas north and west of the Old City and north and south of the White Mosque. Several excavations were also conducted around the Ramla bypass road northeast of the Old City and in the western suburbs of the modern city. The aqueduct that carried water to the city from the springs at Tel Gezer was also examined in salvage excavations. Although they were conducted in non-contiguous areas, the many excavations make it possible to arrive at a tentative reconstruction of Ramla in the Early Islamic, Mameluke, and Ottoman periods. In addition to the excavations, an architectural survey of the buildings from the Middle Ages and the Ottoman period was conducted by A. D. Petersen in the center of the city.

THE COURTHOUSE COMPLEX

In 1994–1995, an area of about 5 a. was excavated by D. Glick on behalf the Israel Antiquities Authority at the site of the new Ramla courthouse. Ten excavation areas were opened, revealing houses, subterranean installations, and cisterns. The evidence attests to continuous occupation through the Early Islamic period. Two inscriptions in Arabic were found dated to the first quarter of the tenth century. Also found were the remains of an olive-oil press and a mosaic pavement with geometric motifs intertwined with figures of animals—birds, what appear to be donkeys eating dates from a tree, and a tiger—all on a white background. In another area, two underground silos were uncovered: one, 8 by 4 m and 4 m deep; the other, 12.6 by 4.6 m and 3.6 m deep. The outer walls of the silos were constructed of fieldstones bonded with mortar and the inner walls were plastered. Their roofs were probably built of barrel vaults. In the southern part of the site were two rectangular pools; one contained traces of red paint and may be the remains of a dyeing industry. Around the pools were remnants of drainage channels, sewage systems, and cisterns.