Safed

THE SITE

Ancient Safed is located on a chalky hill in the mountainous eastern area of Upper Galilee. On the summit of the hill, 834 m above sea level, is an elongated ancient mound, c. 10 a. in area, settled from the Middle Bronze Age onward. In the Crusader and Mameluke periods, towering citadels were built on the hill. A number of medieval and Ottoman quarters, still partly preserved, extended along the slopes of the hill surrounding the citadel. The site is first mentioned by Josephus (War II, 573) as Seph, a site he fortified between Achbara and Yamnit. It is thereafter referred to in numerous Jewish and Arab sources and became the main urban center in the Galilee in the second millennium CE.

HISTORY

Surveys and archaeological excavations of the mound and its slopes have revealed that Safed was first settled in the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000 BCE) and has since been continuously inhabited into modern times. The site may have already been fortified in the second and first centuries BCE, possibly as one of the Hellenistic fortresses and later as one of the Hasmonean garrisons conquered by Herod during his campaign against the Jews of Galilee in 39 BCE (Josephus, War I, 238–239, 314–316; Antiq. XIV, 297–298). Josephus fortified the site in 67 CE in preparation for the anticipated Roman invasion. However, no definite architectural remains of these fortifications have been found. During the Late Roman and Byzantine periods, Safed was probably a medium-sized Jewish town, mentioned once in the Jerusalem Talmud. According to Jewish literary and epigraphic sources, a community of one of the 24 priestly families, Yakim-Pashchur (the twelfth priestly course), lived in Safed. In the Early Islamic period, a Jewish community in Safed is documented in the Cairo Geniza. In the eleventh century CE, just before the Frankish conquest, Arab sources mention the existence of a single tower, Burj el-Yatim. The earliest fortification of the site by the Franks is recorded as dating to 1101/02 CE; this fortress was handed over to the Templars in 1168. Safed was surrendered to Saladin by the Franks in 1188, and the fortress remained in Muslim hands until 1240. Safed was then returned to Frankish rule and a large citadel was built, described as the largest Crusader castle in the East; the details of its building are described in a Latin source, De Constructione Castri Saphet, dated to the year 1264 and attributed to the bishop of Marseilles, Benoît of Alignan. In 1266, the Mamelukes, under the command of Baybars, besieged the fortress, which was surrendered after a six-week siege. According to the historical sources, the Mameluke Sultan undertook reconstruction work as early as 1266–1267, building an outer fortification wall, as well as a huge round tower, 120 cubits (60 m) high and 70 cubits (35 m) in diameter, and fitted with a spiral ramp. Safed, dominated by its castle, became a provincial capital and eventually one of the largest cities in the country. During the sixteenth century, it was a world-renowned center of Jewish thought and mysticism, with a prosperous Jewish quarter on its western slope that encompassed about half the city’s total population (c. 20,000). In 1759 and 1837, earthquakes severely damaged the city, while further hardships in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, together with the development of the coastal cities, brought about an eventual decline in the city’s population and importance, a situation relieved only after the 1948 War of Independence.

SURVEYS AND EXCAVATIONS

Although described by numerous travelers throughout the second millennium CE, Safed’s archaeological remains and ancient buildings were first documented by European explorers and artists in the nineteenth century. A survey of the citadel conducted by the Palestine Exploration Fund produced its first detailed plan. Until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, however, no formal excavations were conducted within ancient Safed. The excavations described below were carried out mainly under the auspices of the Israel Department of Antiquities (IDA) and, since 1990, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).

The first excavations were undertaken in 1951 by M. Dothan and in 1962 by A. Druks within the confines of the citadel, below it, and to the south and southwest of the summit. In 1967 (D. Bahat), and again in 1987 (E. Damati and Y. Stepansky), Middle Bronze Age I–II and Late Bronze Age burial caves were excavated on the southern slope of Mount Canaan, 500 m east of the citadel. During the 1980s, a series of soundings was directed by Damati in different parts of the citadel, and pottery surveys of the mound and its environs were conducted on behalf of the Archaeological Survey of Israel (by R. Frankel et al.) and the IDA (archaeological survey by Y. Stepansky). In the early 1990s, an emergency survey and a salvage excavation of Middle Bronze Age cairns were carried out by Damati and Stepansky prior to the construction of the Ramat Razim and Menachem Begin quarters in the eastern part of Safed’s municipal area. In 1996, a salvage excavation was directed by Damati at the site of Khan ha-Yehudim (Khan el-Pasha) on the southern fringes of the Jewish Quarter. A long-range project for the excavation, preservation, and reconstruction of the southern part of the citadel was initiated in 2001, directed at first by Damati and continued by H. Barbé. Preservation evaluations and architectural surveys of ancient buildings and monuments were also carried out in the Old City by the IAA Conservation Department. In 2002, a small-scale salvage excavation was conducted by Damati in the Artists’ Quarter near the Rimonim Hotel, in front of the Zawiyet Banat Hamid Mameluke mausoleum. A salvage excavation was directed by M. Cohen on the southern fringes of the Mameluke-Ottoman Quarter of Harat el-Wata (a modern neighborhood in the southern section of Safed) and a limited sounding within the compound of Machon Alta on the northwestern slope of the citadel was conducted by Stepansky.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE MIDDLE–LATE BRONZE AGE CEMETERY. Excavations in 1969 and 1987 on the slopes of Mount Canaan exposed the remains of an ancient cemetery. In 1969, five caves were excavated, yielding pottery vessels, metal weapons, and a scarab from the Middle and Late Bronze Ages; the last cave contained imported vessels. In 1987, finds uncovered in three caves consisted of 51 complete pottery vessels, including a storage jar, bowls, jugs, and an alabastron; 28 bronze weapons, among them an ornamented “duckbill” axe, chisel axes, spearheads, daggers, and a knife blade; 24 toggle pins from the Middle Bronze Age IIA, the transitional Middle Bronze Age IIA–B, and the Middle Bronze Age IIB; and a scarab from the late Middle Bronze Age IIB.

THE PRE-CRUSADER MOUND. The ceramic and numismatic evidence from the surveys and soundings, which supplemented the meager historical sources, attests to a history of continuous settlement in pre-Crusader Safed. Evidence of habitation was uncovered from the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, Iron Age I–II, Persian, Hellenistic (a large amount of sherds of the so-called Galilean coarse ware), Hasmonean (a coin of Alexander Jannaeus), Roman (numerous sherds of the Kefar

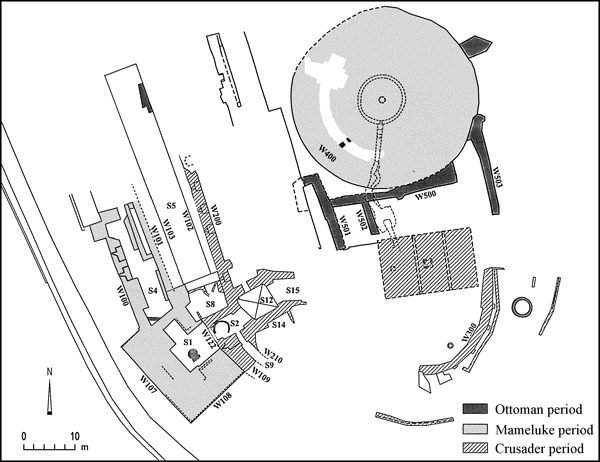

THE CRUSADER PERIOD. The excavations, carried out mainly in the southwestern part of the citadel, uncovered remains of defensive towers and walls with loopholes, vaulted rooms, cisterns, and a moat, all of which belonged to the large thirteenth-century Crusader castle whose construction is recorded by Benoît of Alignan. The castle was oriented north–south. One of its walls, 2 m thick and 25 m long (W200), had five identical loopholes, 1.8 m wide and 1.2 m deep, with oblique slits 9 cm wide. To its south the excavations uncovered part of an imposing curved wall (W109), 6 m long and 3.2 m wide, with a mason’s mark in the form of an axe on one of its stretchers and one loophole set in the wall (A) and subsequently sealed. Between the walls and within their confines was a succession of vaulted rooms (S8, S12, S15). In the debris of the easternmost room (S15) were discovered a sculpted stone head of a saintly figure (originally an architectural element) and a fragment of another head. South of these was a cistern (S14) with a thick coating of hydraulic mortar on its northern and eastern walls (W204, W211). Further to the east, M. Dothan discovered in 1951 another curved wall (W300), supported by small buttresses, with remains of a paved passageway and a water drainage channel opposite its southern facade; to their south, part of the core of an outer curved fortification wall was found in 2001.

THE MAMELUKE PERIOD. After conquering Safed in 1266, Baybars rebuilt the Crusader fortress, adding a massive round tower on the top of the citadel, a well-fortified gateway on the western side of the castle, and probably also a 42 m-long hall (S5). The upper gate tower, 20 by 15 m, with walls 7 m thick, was faced with unusually large blocks, laid as stretchers against a thick core of masonry. Its western wall (W107), with a sloping facade, was never completely buried and appears on the Survey of Western Palestine plan. In the southeastern corner of the tower, where it joins the façade of the Crusader wall of the previous phase, the upper part of a latrine was uncovered. The access ramp, ascending from north to south, is 24 m long and 7–8 m wide. In the vicinity of the entrance to the ramp, sockets of hinges and bolts were found, suggesting the presence of a lower gate with a double door.

Outside the gate, within an accumulation of fallen debris, a large fragment of an ornamented limestone lintel was found; on one of its faces is a carved lion with its right leg raised, probably part of the lintel of the lower gate. This lintel very likely originally bore two lions facing each other, the coat of arms of the Mameluke Sultan Baybars. The ramp consists of a slope with elongated steps and pilasters set at regular intervals on the inner face of its western wall; between them were oblique loopholes and along its eastern side was a corridor (S4) whose function has not yet been clarified. Several cracks in the walls of the gateway structures are evidence of seismic activity; subsequent repairs are seen in the structure of the ramp.

The great round tower at the top of the citadel, built of large limestone blocks, was partly uncovered; it had a circular cistern (10 m in diameter and 10.5 m high) in its center. Surrounding the tower’s upper section was a round corridor. These remains conform well with the “splendid tower” described in Mameluke sources as a spiral ramp leading to the top and attributed to Baybars.

Among the small finds from this period are a large quantity of glass and pottery, including local reddish plain ware, glazed plates decorated with incised motifs, and various imported wares from Syria, Egypt, Italy (Venetian), China (Celadon and Ming), and Spain. A small hoard of 37 silver coins (19 Mameluke and 18 Venetian) from the fifteenth century was also found.

The 2002 excavations directed by M. Cohen on the southern fringes of the southwestern part of the city, somewhat distant from the citadel, also yielded remains of the Mameluke occupation and augment the historical sources that describe Safed as a large city during that period. The remains of the two monumental Mameluke buildings—the Red Mosque and the Zawiyet Banat Hamid mausoleum—also attest to that rich period in the history of Safed.

THE OTTOMAN PERIOD. Ottoman remains appear on the upper level of the citadel, clustered around the round tower and abutting it on its southern side (W500–W503). This construction, set against and above the ruins of the round tower, belongs to Dahir al-‘Umar’s fortress, which was restored after the 1759 earthquake. Until the early nineteenth century, the fortress continued to function as a military and administrative center; it was briefly occupied by a contingent of Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops in 1799. It suffered several earthquakes throughout its history, but the earthquake on January 1, 1837 left it in ruins. The site subsequently served as a stone quarry for the rebuilding of the city below, while the government center moved to the Turkish Saraya building to the south.

The 1996 excavation of part of the Khan ha-Yehudim (Khan el-Pasha) building complex within the Jewish Quarter, coupled with a study of surface remains and sixteenth- and seventeenth-century literary sources mentioning this unique building, enable a proposed reconstruction of its size and plan. It was abandoned in the mid-seventeenth century.

EMANUEL DAMATI, YOSEF STEPANSKY, HERVÉ BARBÉ

THE SITE

Ancient Safed is located on a chalky hill in the mountainous eastern area of Upper Galilee. On the summit of the hill, 834 m above sea level, is an elongated ancient mound, c. 10 a. in area, settled from the Middle Bronze Age onward. In the Crusader and Mameluke periods, towering citadels were built on the hill. A number of medieval and Ottoman quarters, still partly preserved, extended along the slopes of the hill surrounding the citadel. The site is first mentioned by Josephus (War II, 573) as Seph, a site he fortified between Achbara and Yamnit. It is thereafter referred to in numerous Jewish and Arab sources and became the main urban center in the Galilee in the second millennium CE.

HISTORY

Surveys and archaeological excavations of the mound and its slopes have revealed that Safed was first settled in the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000 BCE) and has since been continuously inhabited into modern times. The site may have already been fortified in the second and first centuries BCE, possibly as one of the Hellenistic fortresses and later as one of the Hasmonean garrisons conquered by Herod during his campaign against the Jews of Galilee in 39 BCE (Josephus, War I, 238–239, 314–316; Antiq. XIV, 297–298). Josephus fortified the site in 67 CE in preparation for the anticipated Roman invasion. However, no definite architectural remains of these fortifications have been found. During the Late Roman and Byzantine periods, Safed was probably a medium-sized Jewish town, mentioned once in the Jerusalem Talmud. According to Jewish literary and epigraphic sources, a community of one of the 24 priestly families, Yakim-Pashchur (the twelfth priestly course), lived in Safed. In the Early Islamic period, a Jewish community in Safed is documented in the Cairo Geniza. In the eleventh century CE, just before the Frankish conquest, Arab sources mention the existence of a single tower, Burj el-Yatim. The earliest fortification of the site by the Franks is recorded as dating to 1101/02 CE; this fortress was handed over to the Templars in 1168. Safed was surrendered to Saladin by the Franks in 1188, and the fortress remained in Muslim hands until 1240. Safed was then returned to Frankish rule and a large citadel was built, described as the largest Crusader castle in the East; the details of its building are described in a Latin source, De Constructione Castri Saphet, dated to the year 1264 and attributed to the bishop of Marseilles, Benoît of Alignan. In 1266, the Mamelukes, under the command of Baybars, besieged the fortress, which was surrendered after a six-week siege. According to the historical sources, the Mameluke Sultan undertook reconstruction work as early as 1266–1267, building an outer fortification wall, as well as a huge round tower, 120 cubits (60 m) high and 70 cubits (35 m) in diameter, and fitted with a spiral ramp. Safed, dominated by its castle, became a provincial capital and eventually one of the largest cities in the country. During the sixteenth century, it was a world-renowned center of Jewish thought and mysticism, with a prosperous Jewish quarter on its western slope that encompassed about half the city’s total population (c. 20,000). In 1759 and 1837, earthquakes severely damaged the city, while further hardships in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, together with the development of the coastal cities, brought about an eventual decline in the city’s population and importance, a situation relieved only after the 1948 War of Independence.