Sepphoris

HISTORY

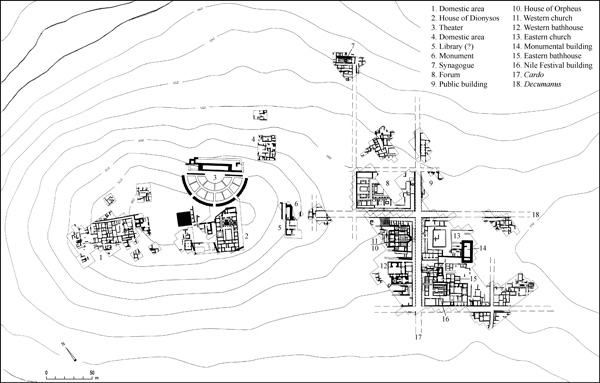

Sepphoris grew considerably during the Roman period and sustained damage in the mid-fourth century, most probably caused by the earthquake of 363 CE. It has become evident that Sepphoris’s civic center, which was constructed during the Roman period in the lower city, expanded in the course of the Byzantine period, though the basic plan of the city remained largely unchanged. It is not yet possible to determine when and how its magnificent buildings were destroyed or when its population decreased. It is clear that there was a decline at the site during the Islamic period, reflected in abandonment and destruction of earlier structures, the looting of earlier masonry, and the construction of simple buildings scattered about the site.

EXCAVATIONS

In 1990–2002, four teams worked in various parts of the city, the excavation of which is an ongoing project. The Hebrew University team (directed by E. Netzer and Z. Weiss through 1994 and by Z. Weiss from 1995) worked on the summit and in the lower city, with most of the excavations taking place in the latter. The Duke University team (directed by E. M. Meyers, C. L. Meyers, and K. Hoglund) conducted work in the domestic area on the western summit. The University of South Florida team (directed by J. F. Strange) unearthed the public building northwest of the intersection of the two central streets in lower Sepphoris. A systematic survey and excavation of the water system to the east of the site was carried out by Tel Aviv University (directed by T. Tsuk).

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE ROMAN PERIOD. Stone quarries found over a small part of the western summit indicate that this area was not yet used for residential purposes in the Hellenistic period, however, remains of a building with massive walls and two mikvehs dated to the early first century BCE were encountered on the easternmost edge of this area.

During the Early Roman period, dwellings were constructed on the western summit, their plans apparently typical of Galilean domestic architecture. These houses remained in continuous use to the end of the Roman period, undergoing numerous changes through the years. Many painted plaster fragments characteristic of the Herodian period, found below the floors of the House of Dionysos on the eastern summit, may indicate that a first-century CE building once stood there.

Early in the second century CE, the city expanded considerably eastward, boasting an impressive network of streets arranged in a grid, with two colonnaded streets, the cardo and decumanus, at its center. Both of the streets are c. 6 m wide and paved in slabs of hard limestone laid in diagonal rows. On either side of the colonnaded streets were porticoes, which were probably originally paved in mosaic; they were backed by shops, where most of the city’s business and commercial activities probably took place from the second century CE onward. The other streets that run parallel to the cardo and the decumanus were paved in flagstones or lime plaster. Some of the new streets east of the acropolis were supposedly linked to the existing ones on the hill itself and to those continuing beyond the city limits, connecting Sepphoris with its agricultural hinterland and inter-urban roads.

Three Public Buildings in the Lower City. Public buildings, some monumental, were constructed during the Roman period in lower Sepphoris, adjacent to the major routes and on the hill and its slopes. Two public structures were partly unearthed to the east of the cardo; one is located in the insula to the south of the decumanus, the other to its north. Of the first building, only the foundations were preserved. This structure, the function of which has yet to be established, measures 23 by 12 m, its long axis running in a general north–south direction. The structure is located within a large courtyard. Remains from another building, which probably occupied the entire insula to the north of the decumanus, are several rooms on its western side and shops with vaulted ceilings facing the street to its north.

A large structure (40 by 60 m) occupying an entire insula was excavated immediately to the northwest of the intersection of the cardo and the decumanus. The building, identified by the excavator as a basilical hall, comprised a peristyle courtyard surrounded by many rooms of various sizes, as well as some underground cisterns. According to the published material, the building should be identified as a forum, a freestanding edifice linked to the street network, similar to those known in other provincial cities. It was constructed in the Early Roman period and was in continuous use until the mid-fourth century CE. Several rooms within the building were decorated with painted plaster, which included rectangular panels in shades of red, blue, and yellow. The building’s floors were furnished with mosaics depicting an acanthus scroll, a Nilotic landscape, and geometric designs. One mosaic unearthed in a large hall (8.5 by 6 m) along the western side of the building is decorated in a geometric pattern of interlacing circles with a partially preserved 1.5 m square panel near the center of the pavement. Each of the circles contains a square panel inhabited by a variety of motifs, usually birds and fish; a syrinx, a shallow basket of fruit, a hare nibbling grapes, flowers, and pomegranates also appear.

The Bathhouses. Two Roman bathhouses were located on either side of the main colonnaded street of Sepphoris. The eastern bathhouse, dated to the late first or early second century CE, is a small structure. It includes several rooms, some of which were paved with simple mosaics; among them are a rectangular caldarium, a room with a stepped pool (mikveh), and two barrel-vaulted cisterns. The western bathhouse, constructed late in the Roman period and in use through the Byzantine period, is almost square in plan (27 by 26 m). Its rooms were arranged around a central courtyard paved with flagstones. A single row of rooms flanked the western, northern, and eastern sides of the courtyard; in the middle of the northern row was an exedra opening onto the courtyard. Two rows of rooms were built to the south of the courtyard. The first row included several pools, the second the caldaria. The westernmost of the three caldaria was octagonal in plan, the other two square.

The Monumental Building and Adjacent Structure. A monumental building was unearthed along the eastern edges of the hill, facing the lower city to the east. This building, measuring 16.80 by 14.50 m, includes a peristyle courtyard surrounded by three aisles and a row of rooms to its south, of which only the western is well preserved. This room has thick walls (1.15 m wide) with niches (0.74 m wide, c. 0.46 m deep). Slits found within the two well-preserved niches indicate that they may have held wooden shelves. The location of the building within the urban complex and its characteristics may indicate that it functioned as a public building, perhaps a library or an archive. The building was constructed in the Roman period, although it is not yet clear whether it is contemporary with or slightly predates the structures from the Roman period in the lower city. At a later stage of its use, probably close to its final years, the building lost its splendor and was utilized for private purposes. Partition walls were added between the columns of the peristyle courtyard, entrances were blocked, and the room with the niches was converted to a stable. The heavy collapse found throughout the building indicates that it was destroyed, presumably during the fourth century CE, and never rebuilt.

Two massive parallel walls were unearthed outside and adjacent to the monumental building. The walls are built of fieldstone and are aligned on a northeast–southwest axis, perpendicular to the slope. Several pieces of architectural ornament found in the debris are indicative of the prominence of the destroyed structure, which was perhaps a monument constructed on the slope. The surviving walls would have been retaining walls for the monument above, with its corner columns and Corinthian capitals. The structure was erected in relation to the westernmost edge of the decumanus and lies on its axis, providing a point of visual reference for those heading towards it on the street.

The Theater. The theater, located on the steep northern slope of the hill, was built in the early second century CE and went out of use in the course of the fifth century. It was 74 m in diameter and could seat 4,500 spectators. The cavea was divided into two horizontal blocks, most of its seats and steps having been robbed. The structure had five entrances: three vomitoria around the cavea and two parodoi leading to the orchestra. The scaena and the stage (35 by 6 m) are almost completely destroyed, except for their foundations, but several architectural fragments found in this spot indicate that the scaenae frons was lavishly ornamented. The proscaenium was decorated along its entire length with alternating square and semicircular niches embellished with miniature flat pilasters. Certain parts of the theater, like the eastern parodos, were adorned with painted plaster. Several layers of painted lime plaster were revealed, some of which included floral and geometrical designs in shades of green, yellow, and brownish-red.

Domestic Architecture. Private dwellings at Sepphoris are found throughout the city. Houses of a simple character were exposed on the western part of the hill, on its northern slope (close to the theater), and in the lower city, alongside the public buildings that were erected there. In some cases, the houses constructed in the Roman period remained in use, with certain modifications, in the Byzantine period. They were constructed of fieldstone and some cut stones of mediocre quality. Floors were paved in plaster; simple fragmentary mosaics were occasionally found in a single room of the dwellings. The structures contained variously sized rooms, courtyards, silos, and underground storerooms, as well as water installations including cisterns and a large number of ritual baths (mikvehs). The plan of these houses is not yet entirely clear, but it appears that in some, ground-floor rooms were arranged around an open courtyard while storerooms and water installations were in basements. Some had second stories. Evidence of industrial or commercial activities, such as a winepress and large ovens (tabuns), was found in several places. Most of the city’s population presumably resided in similar houses, which probably covered most of the area of the hill and its slopes.

Large, spacious, and well-planned residences, intended for the city’s wealthy inhabitants, were erected next to the simpler homes. Their walls were of well-dressed stones and in most cases their floors were decorated with colorful mosaics, some featuring figural representations. The largest and most important found to date, located on the hill, is the House of Dionysos, constructed around 200 CE. The building measured 45 by 23 m and, in all probability, had a second story that covered only its northern and central parts. A courtyard surrounded on three sides by columns was located in the center of the building. The northern part boasted a triclinium, which opened onto the courtyard via three doors. The other rooms were arranged around the triclinium and the peristyle courtyard. The rooms south of the courtyard were on two levels, one at the elevation of the courtyard and the other below it. Some of the rooms on the lower level served as storerooms, while those on the south, which opened onto the street that ran along the southern edge of the hill, functioned as shops; an olive-oil press was found in one of these rooms. Many of the rooms were originally paved with mosaics featuring colorful geometric patterns, the most important mosaic being that found in the triclinium (see Vol. 4, pp. 1324–1328). The interior walls of the building were coated in several layers of plaster. Painted plaster was preserved in situ in one place only, but the many fragments revealed in the debris that covered the building may indicate that other rooms were also decorated with colorful painted plaster, which includes geometric and floral patterns.

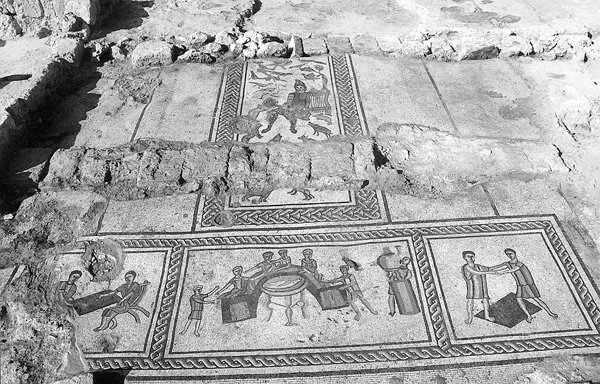

Other large dwellings with a similar layout, though on a smaller scale, were constructed in Roman Sepphoris, indicating the popularity of such homes and the wealth of their owners. One example, located adjacent to the intersection of the cardo and the decumanus and north of the western bathhouse, measures 28.5 by 17 m and is named after the splendid mosaic depicting Orpheus that graces its triclinium. The building has three entrances, from the north, east, and south, the primary of which appears to have been the eastern, with its small stone-paved antechamber located next to the cardo. The lavishly decorated triclinium is abutted on the south by a partially reconstructed courtyard with two aisles. Various rooms were uncovered around the triclinium and the courtyard, some of which contained mosaics with simple designs. The T-shaped mosaic in the triclinium is composed of four colorful panels, arranged for viewing from the south. Orpheus, the divine musician, is depicted in the central carpet. He sits on a rock and plays a string instrument, calming the wild animals and birds that surround him. The three other panels portray scenes from daily life: a banqueting scene in the larger middle panel, two men playing dice in the left panel, and two men embracing in the right.

The building was constructed in the second half of the third century CE and probably destroyed by an earthquake in the mid-fourth century CE, then immediately renovated. The restored building retained the original plan with some internal changes, but was paved with new mosaics, laid 10 cm above the earlier ones. Several rooms had simple white mosaics, others geometrical designs, and some figural depictions, only few traces of which are preserved. The building was completely destroyed at the beginning of the fifth century CE.

Three other structures were partly excavated throughout the city. One such building, on the western side of the hilltop, was initially excavated by L. Waterman (see Vol. 4, p. 1327). The second building is located north of the building identified as a forum; its sole remains are a peristyle courtyard paved with colorful mosaics and several adjacent rooms. The third structure is located in the southeastern-most excavated area in lower Sepphoris. Analysis of the remains indicates that the building was designed on two levels. The lower of these was constructed around a peristyle courtyard with a fountain at its northern end; the upper level extended over the building’s length and was reached via a staircase located to the west of the peristyle courtyard. Various rooms within the building were paved with mosaics, including simple colorful geometric designs, severely damaged; others had plaster floors.

The Farmhouse. A farmhouse east of the site, along the road leading toward the reservoir and the cemeteries in the city’s periphery, was partly excavated. It includes five rooms located to the north and east of an open courtyard, as well as one nearby agricultural installation, most probably a winepress. Various agricultural tools were found in the debris of the farmhouse. It was constructed in the third century and destroyed in the course of the fourth century CE.

The Water Supply System. Additional work was conducted in the reservoir, which was constructed in the second century CE and remained in continual use through the Byzantine period, until around the seventh century. It measures 260 m long, 3 m wide, and 10 m high, and has a capacity of 4,300 cu m. Water entered the reservoir from the east, through a chute that fed into a square settling tank cut into bedrock. A drain was located on the western side of the reservoir, through which water flowed through a stopper into a 234 m-long conduit set in a tunnel with six vertical shafts cut in bedrock. To the west of the tunnel, the conduit emerges on the surface and runs toward the city in a channel constructed on bedrock and covered with stone slabs. The location where the aqueduct entered the city has not yet been verified.

THE BYZANTINE PERIOD. The network of roads and streets established during the Roman period continued to function in the Byzantine period. Significant changes to the urban layout were introduced close to the intersection of the cardo and the decumanus. The porticoes along the colonnaded streets were renovated and adorned with mosaics displaying simple black-and-white geometric patterns. Three medallions of different sizes integrated in the mosaics contained dedicatory inscriptions recording that the renovation was carried out in the days of Eutropius, bishop of the city.

Evidence for Byzantine activity was found mainly in the lower city. Several public buildings were constructed during this period, while some earlier Roman structures, such as the theater and the western bathhouse, continued in use. An open plaza with shops and a colonnade in front of them were built over the ruined eastern bathhouse, opening onto the cardo. A small rectangular structure, probably the base of a monument, was located on the eastern side of the plaza, opposite the western entrance. A second bathhouse, constructed during the Byzantine period, was partly unearthed on the eastern side of the destroyed forum, thus concealing the remains of the earlier building. It includes a caldarium with some plastered pools adjacent to it. Several rooms of various sizes were excavated to their south. Some rooms were paved with mosaics, the largest of which contains floral designs.

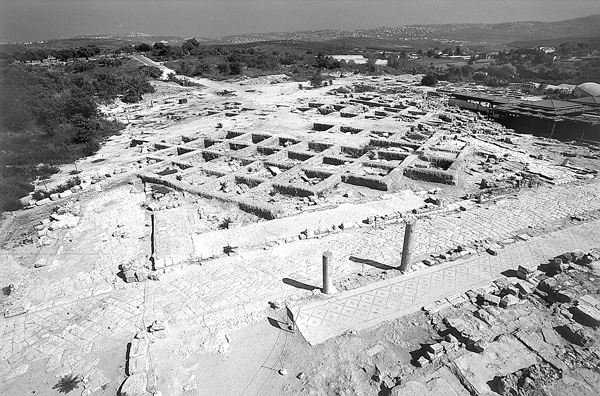

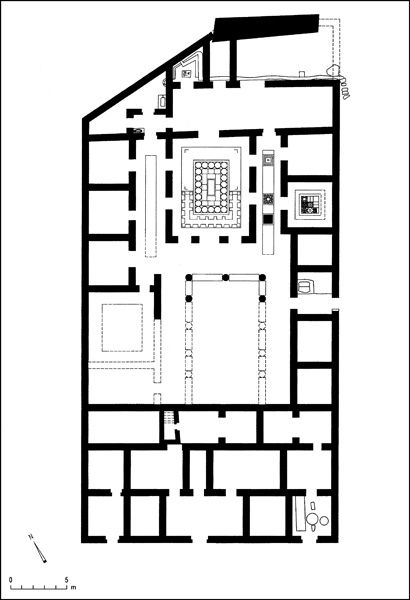

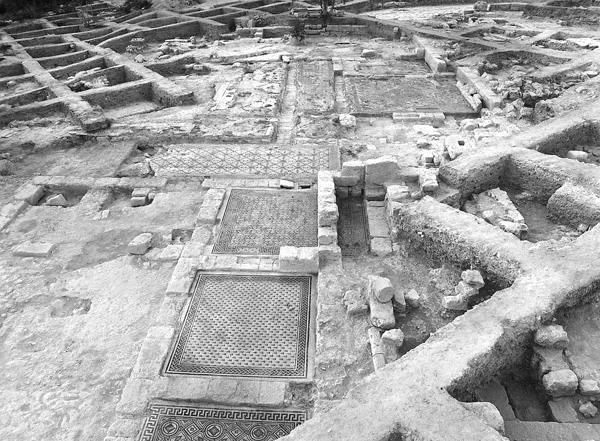

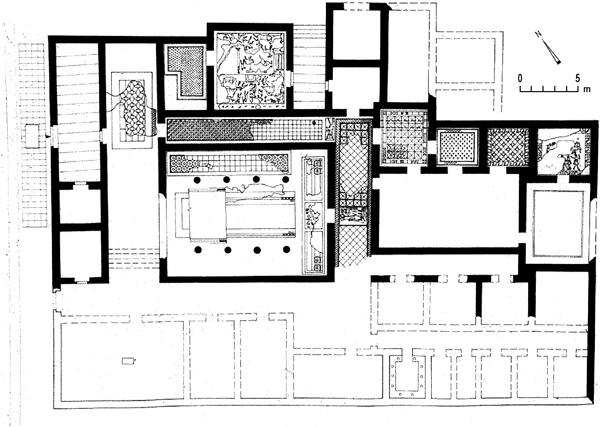

The Nile Festival Building. Constructed in the early fifth century CE, the Nile Festival building is located to the east of the cardo, opposite the western bathhouse. The building was somewhat irregular in plan; its overall layout approximates an elongated rectangle measuring c. 50 by 35 m. It has at least two entrances, one on the west from the cardo, the other on the north. A mosaic floor containing an eight-line inscription referring to the building was laid on the sidewalk in front of the western entrance. The structure’s central location within the city, its artistic richness, size, and numerous rooms, as well as the fact that it bore no characteristic features of a dwelling, indicate that it was a public building, perhaps a municipal basilica.

A basilical hall measuring 15 by 10 m, flanked by corridors on all four sides, was located at the center of the Nile Festival building. The largest and most important of the rooms surrounding this hall is that carpeted in the Nile Festival mosaic (see below). To the east of the basilical hall was probably an inner courtyard surrounded by rooms of various sizes. Noteworthy among the surviving rooms is one that served as a latrine. The entire building was paved with mosaics, some of which are very well preserved. Certain rooms were decorated with figural mosaics, but most of them, as well as the corridors, had geometric designs, some of which show a particularly rich array of patterns and colors.

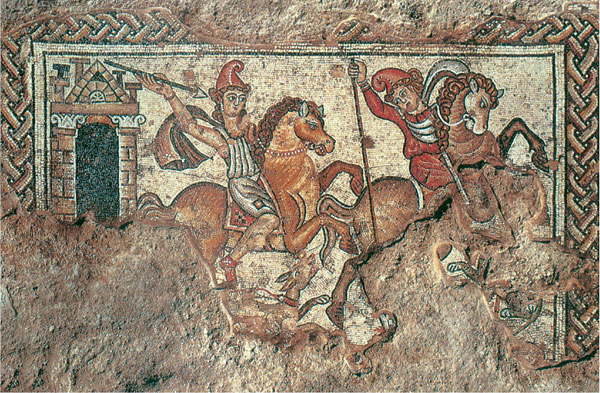

In several cases, figural panels were incorporated within geometric carpets. One panel, located in the central part of the building, depicts two figures riding on galloping horses—a huntress, probably an Amazon, and a male warrior. The two appear to have killed a lion and are attacking a panther chased by a hunting dog. Additional panels appear in the geometric mosaics decorating the corridors to the north and east of the basilical hall. One depicts a centaur leaping on his hind legs and the other portrays two naked hunters standing next to a tree, with a wild boar at their feet.

Two of the rooms were decorated with figural mosaics that fill the entire floor area. (Some of the rooms whose floors are missing may have been similarly decorated.) In the easternmost room of the building is a partially preserved mosaic depicting Amazons. The largest and most impressive in the building, however, is the Nile Festival mosaic. The carpet (6.7 by 6.2 m) features a combination of Nilotic scenes and various hunting scenes. A nilometer is depicted in the upper central part of the mosaic, upon which a man standing on the back of another crouched figure carves the letters IZ with a hammer and chisel. Two large reclining figures of a man and a woman appear in the upper two corners of the carpet: to the right, a male personification of the Nile, sitting on an animal from whose mouth the river’s waters issue forth; to the left, a half-naked female personification of Egypt’s fertile soil. The other scenes on the floor are related to the Nile and the city of Alexandria; they are accompanied by various hunting scenes.

The Synagogue. A synagogue dated to the early fifth century CE was built in the northern part of the city, over ruined structures dated to the Roman period. It remained in use until the early seventh century CE. It is an elongated building (c. 20.8 by 7.7 m), not facing Jerusalem, with an entrance in its southern side and an asymmetrical interior. It walls, most of which have been robbed to floor level, were of fairly large ashlars. The entrance room (narthex), originally paved with a mosaic floor decorated with geometrical designs, was built at the narrow end of the building, in the east, with a rectangular water cistern underneath it. The main hall (16.1 by 6.5 m) was divided in two by a row of five columns, looted in antiquity. These stood on pedestals with a simple profile, only one of which has been preserved in situ. Remains of the bema, measuring 5 by 2.4 m, were unearthed on the western end of the nave.

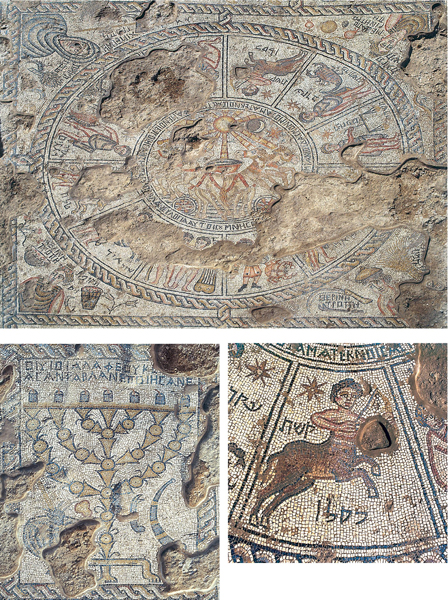

The most significant remnant of the synagogue is its mosaic floor, which was designed as a single long carpet. The mosaic in the main hall has a figural design, whereas that in the aisle is of geometrical designs encompassing several Aramaic dedicatory inscriptions. The main hall’s carpet is divided into seven horizontal bands of unequal height, some internally subdivided, for a total of 14 panels. The panels contain a variety of representations, as well as dedicatory inscriptions, mostly in Greek, which bear no relationship to the adjacent scenes.

The upper half of the first (or uppermost) band was completely destroyed as a result of the looting of the bema stones. It depicts a stylized wreath with a Greek dedicatory inscription flanked by two lions, each gripping a bull’s head. In the second band is an architectural façade, a menorah on either side of the façade, a bowl containing the four species, a shofar, tongs, and an incense shovel below the façade. In the third and fourth bands are depictions related to the Tabernacle or Temple. Aaron’s consecration to the service of the Tabernacle (Ex. 29), presented in the third band, is comprised of three episodes, viewed from right to left. A basin containing water is depicted to the right, then a large altar with the mostly destroyed figure of Aaron next to it, followed by the presentation of sacrifices. The continuation of this scene appears in the left panel of the fourth band, where the perpetual sacrifice, offered daily in the Tabernacle and later in the Temple, is depicted. The other two panels in the fourth band present other aspects of the Temple cult: the central panel contains the shewbread table; the right panel, a wickerwork basket containing first fruits.

The fifth or largest band is the zodiac panel. The inner circle of the zodiac is occupied by the sun (not, in this instance, personified as Helios) riding a chariot drawn by four horses. The outer circle consists of the 12 signs of the zodiac. A youth and a star accompany most of the signs; the youth usually wears a cloak that covers the upper part of his body. The names of the signs of the zodiac and their respective months appear in Hebrew. Allegories of the four seasons, accompanied by Hebrew and Greek inscriptions, are represented in the corners of the square delimiting the zodiac’s outer circle. Several artifacts representing the agricultural activities symbolic of each season appear beside them.

The sixth and seventh bands portray scenes connected with Abraham. The story of the binding of Isaac is depicted in the sixth band, whereas the last band, located adjacent to the doorway of the synagogue hall and largely destroyed, presents the visit of the three angels to Abraham at Mamre. The variety of subjects represented in this mosaic and its iconographic richness give it an important place in the study of Jewish art and its relation to early Christian art. Its main theme is that God is the center of creation. He has chosen His people, the people of Israel, and in fulfillment of His promise to Abraham on Mount Moriah, He will rebuild the temple and redeem the children of Abraham.

Churches. Two churches dated to the late fifth or early sixth century CE, most probably to the time of the abovementioned bishop Eutropius, were partly excavated along the cardo, close to its intersection with the decumanus. The building to the west of the cardo is better known. An open plaza (8 by 10 m) with a simple mosaic pavement is located between the decumanus and the church’s northern long wall, providing access to the atrium and through it, into the prayer hall of the church. The church is an elongated building, c. 18 m wide, its length not yet determined. The foundations, composed of fieldstones of different sizes (with the exception of the apse, which was built of hewn stones) are all that remain of the building, which contained a prayer hall flanked by several rooms. In addition, two large cisterns were revealed within the building, one located adjacent to the apse, the other to the southwest of the main hall. The church’s foundations and the fill within them created a sort of podium, thus raising the building above the level of its immediate surroundings.

The foundations of the second church, c. 19 m wide and of undetermined length, were exposed to the east of the cardo, directly opposite the abovementioned church. The prayer hall was partly excavated, though the apse on the eastern side of the building has not yet been exposed. On the western side of the church is a colonnaded courtyard paved with flagstones. A number of rooms, some of which are located to the south of the courtyard and paved with mosaics, were uncovered next to the church. Several architectural elements belonging to the church were found inside the building, including one capital decorated with crosses.

Domestic Architecture. Private houses in the lower city were found east of the Nile Festival building, north of the central insula, and next to the synagogue. Some buildings date back to the Roman period, but were still in use during this phase as well. In one dwelling, located on the southeastern side of the excavation, evidence of dismantling and subsequent rebuilding in the mid-fourth century was detected. Its floors were decorated with colorful mosaics, all featuring geometric designs except for one, a largely destroyed figural mosaic portraying several animals next to a tree.

Construction on the Hill. Various Byzantine period remains were revealed on the hill. Noteworthy are portions of buildings exposed to the west of the hill, a storehouse uncovered in front of the citadel, and several structures located above and inside the ruins of the House of Dionysos. The latter structures, which also contained a number of ritual baths, were of fieldstone and incorporated ashlars in secondary use. The shops and workshops in the basement of the House of Dionysos were restored and continued to function during the Byzantine period. Other dwellings were exposed north of the theater. One of these, exhibiting a very high standard of construction, contained a colorful mosaic floor decorated with geometric designs, birds, and pomegranates.

ZEEV WEISS

Color Plates

HISTORY

Sepphoris grew considerably during the Roman period and sustained damage in the mid-fourth century, most probably caused by the earthquake of 363 CE. It has become evident that Sepphoris’s civic center, which was constructed during the Roman period in the lower city, expanded in the course of the Byzantine period, though the basic plan of the city remained largely unchanged. It is not yet possible to determine when and how its magnificent buildings were destroyed or when its population decreased. It is clear that there was a decline at the site during the Islamic period, reflected in abandonment and destruction of earlier structures, the looting of earlier masonry, and the construction of simple buildings scattered about the site.