Umm el-‘Umdan, Khirbet (Modi‘in)

INTRODUCTION

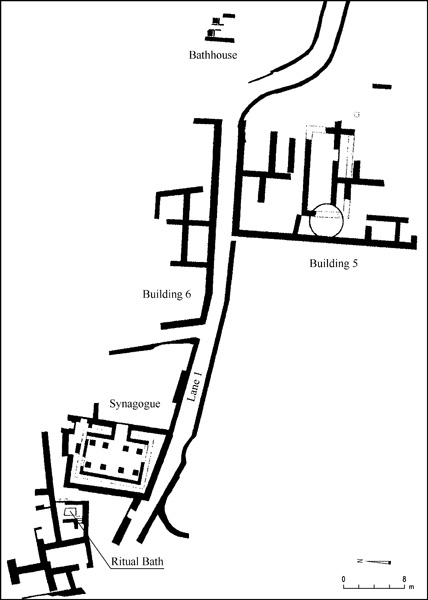

Khirbet Umm el-‘Umdan, located within the municipal boundaries of Modi‘in, was first described by C. Clermont-Ganneau after a visit in 1873, then by C. R. Conder and H. H. Kitchener in their Survey of Western Palestine in 1883. From 2000 to 2003, prior to the construction of a new neighborhood in Modi‘in, excavations were conducted south of the ruin by A. Onn and S. Weksler-Bdolah on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The finds revealed that the ancient site extended over an area of about 6 a. and was established in the Hellenistic period, at the end of the third or beginning of the second century BCE, then occupied continuously at least until the Second Jewish Revolt. The site, with lanes, buildings, a synagogue, and a mikveh, was identified as a Jewish village. Remains of buildings and agricultural installations from the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods (sixth–tenth centuries) overlay the Jewish village. The latest remains uncovered were graves from the Late Islamic period and a lime kiln that had been dug into the buildings, causing considerable damage.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

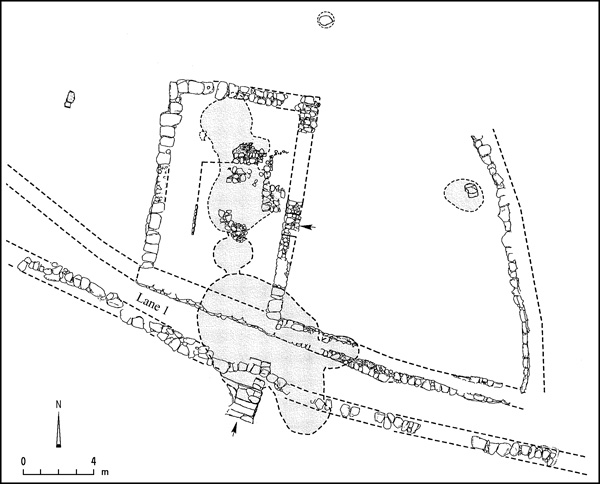

THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD. Two structures on the site—buildings 1 and 5—date from the end of the third to the beginning of the second century BCE. They were connected by lane 1. Building 1 consisted of a rectangular hall (7 by 3.80 m) surrounded by a fortified courtyard, from which a narrow corridor led into the hall. The corridor, which was L-shaped, extended along the southern and western sides of the hall to the main entrance in the middle of the long western wall. The floor of the hall was of beaten earth; on its northern side it was of leveled bedrock. Two partly preserved installations were cut into the bedrock: one, with a round opening (0.5 m in diameter), apparently served as an underground storeroom; the other, carved into the bedrock floor in the northern part of the hall and integrated within the northern wall, was in the shape of a rectangular niche (0.8 m wide, 0.4 m long, height unknown). The date of the hall could be established on the basis of six Seleucid coins of Antiochus III and Antiochus IV Epiphanes and of sherds recovered from the floors of the hall and courtyard and on the lane to the south. The function of the building in this period could not be determined. It may have been a public building, as suggested by its plan of a single central space with a long entrance corridor providing indirect access to the building. This view is corroborated by the fact that the public building identified by the excavators as a synagogue, which was built superimposed over the hall, was of a plan dictated in design and form by the hall itself.

Building 5, in the eastern part of the site, was only partially preserved; its size has been estimated as 25 m by 16 m. In the center of the building was a quadrilateral courtyard enclosed by a row of rooms on its northern and southern sides.

THE HASMONEAN PERIOD. Compared with the previous period, the site underwent considerable development in the period dated from the end of the second and the first century BCE up to the time of Herod. A somewhat larger quadrilateral hall (10.5–11.5 by 6.7 m) was built above the hall and corridor of the Seleucid period, making use of their external walls. A large courtyard enclosed it on the eastern, northern, and western sides. It has been identified as a synagogue.

The hall was entered from the courtyard through a doorway in the eastern wall. A prominent feature of the hall was the U-shaped benches running along three of its walls, though not exactly parallel to them. The benches, preserved to a height of about 0.2 m above the floor, were 1.5–1.7 m wide on the western and eastern sides and up to 3.5 m wide on the northern. It is difficult to determine whether the benches originally formed a low, wide, raised surface around the central part of the floor, like the benches in the synagogue at Qiryat Sefer (Khirbet Badd ‘Issa), or were the base of a more complex structure that contained a number of stepped benches, as at Masada, Herodium, and Gamala. In the center of the hall were the remains of a stone-paved floor built of fieldstones with a smoothed upper surface. Two installations stood in the center of the floor. The northern one was a kind of square bema (1.1 by 1.1 m) paved with medium-sized and large fieldstones, whose upper surface was left rough and projected about 0.10 m above floor level. To its south was another installation built of small fieldstones incorporated into the floor; its round base (1 m in diameter) was preserved. The walls of the hall were decorated with wall paintings, as is evidenced by the many fragments of red, yellow, and white painted plaster found on the floor.

Beneath the hall and to its south was an intricate network of rock-cut subterranean rooms that were only partly investigated. In one of the rooms was a rock-cut cistern that contained intact and broken pots of the Hasmonean period. A small stone column found in another room may have been the leg of a stone table. Found in the courtyard was a small tub probably used for bathing, of the type widespread in sites of this period. Rock-cut storage installations were also uncovered.

The Hasmonean hall has been identified as a synagogue in a Jewish village. Its internal plan was focused on the center of the hall, which suggests that it served as a place of assembly for a large congregation, with the benches along the walls providing a place for the worshippers to view the reading of the Torah in the center. The splendor of the hall also confirms its interpretation as a synagogue. The entrance of the building was moved to the eastern wall, probably in accordance with the usual custom of having the entrance to prayer halls on the east (Tosefta Meg. 3:22) as in the Tabernacle (Num. 3:38). The walls were built of large trimmed stones and the floors were of white ground limestone. Among the installations set in the floors of the rooms were a small bathtub and beneath the floors were underground storage facilities. Lane 1, which was preserved south of the synagogue, connected it with building 5b, in the center of which was an atrium-like courtyard (11 by 5 m) surrounded by rooms.

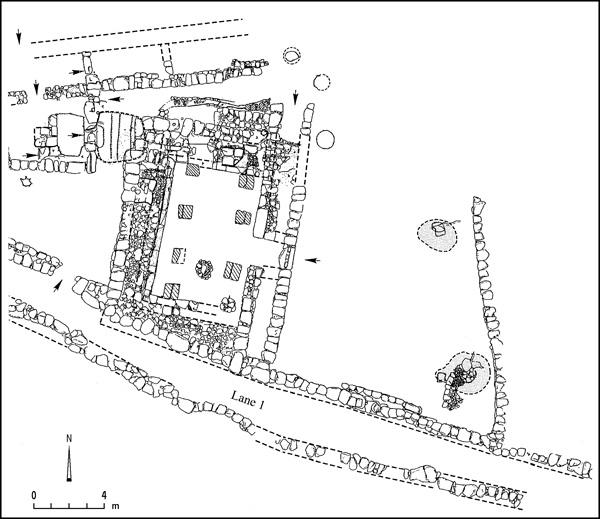

THE HERODIAN PERIOD. The synagogue hall was enlarged to the east in the second half of the first century BCE; the walls of the previous Hasmonean synagogue were reused on the other sides of the hall. The new hall was quadrilateral in plan (10.5–11.5 by 8.6 m), its main entrance in the middle of the eastern wall. Another entrance was opened in the northern wall. The hall in this period had two rows of four columns and two or three stepped benches (overall width, 1.7 m) extended along its sides. The benches were, in most cases, preserved to the height of the lower tier only. The central part of the northern bench, although only partly preserved, was two tiers high and specially fashioned; it may have been a seat of honor. It also remains possible that its shape derived from the need to allow passage from the northeastern entrance into the hall. The floor of the hall was of crushed chalk. A new plaster floor was laid over it at some point, probably at the beginning of the first century CE.

The Herodian hall has also been identified as a synagogue, because it remained a public building within a Jewish village. Moreover, it was constructed directly above the Hasmonean synagogue after no period of disuse, preserving its size, broad-house plan, and eastern entrance. Additional corroboration for this identification stems from its similarity with the synagogues at Masada, Herodium, Gamala, and Qiryat Sefer.

In the first half of the first century CE, a new building containing a mikveh (building 4) was constructed west of the synagogue. The mikveh was entered from the lane separating it from the synagogue. It consists of two rock-cut subterranean rooms and was coated with gray hydraulic plaster. In rooms adjacent to the mikveh were found two stone seals, one fashioned from the handle of a “measuring cup,” which bears a four-letter Aramaic inscription in a crude Jewish script. It has been read by J. Naveh as

On the eastern side of the site, residential building 5 of the previous period continued in use with minor changes. To the east of the building, a bathhouse fitted with a hypocaust was partly uncovered. Throughout the site there were signs of a violent destruction, as in ash layers in the synagogue and in the collapse of adjoining buildings. Coins from Year 2 and Year 3 of the First Jewish Revolt recovered from the debris of the buildings allow the destruction to be attributed to an event that took place during the revolt. A coin of Nero from 68 CE found in the new plaster floor that sealed the destruction level in the hall of the synagogue attests that the destruction occurred prior to 68 CE. In the opinion of the excavators, this destruction was a repercussion of the military campaign of the Roman governor Cestius Gallus, who passed by the site on his march to Jerusalem at the end of 66 CE (Josephus, War II, 515–516).

THE PERIOD BETWEEN THE FIRST AND SECOND REVOLTS. The latest building phase that can be attributed with certainty to the Jewish village began with the repair of the damages of the destruction, probably during the First Jewish Revolt itself, and continued with the construction of new buildings above the destruction level at the end of the first or beginning of the second century CE. The synagogue and its immediate surroundings were cleared of debris. In the synagogue hall, the abovementioned plaster floor was hastily laid, without a foundation, above the destruction level. The northern entrance was blocked and replaced with a new entrance in the northern end of the eastern wall. The mikveh west of the synagogue remained in use with minor changes; a coin of Year 2 of the Second Jewish Revolt (133 CE) was found nearby. Above the ruins of building 5, a flimsy structure with a few rooms and installations was constructed at this time; to its north, a new building with several rooms was erected (building 6). In the latter building, coins were recovered from the time of Domitian (81–96 CE) and Marcus Aurelius (161–180 CE), as were Roman discus lamps of a type that had not been widely used in the Jewish village.

This swift repair of the ruins was presumably carried out by the Jewish inhabitants of the village who returned during the First Jewish Revolt, shortly after the village’s destruction. Its reconstruction may have been possible due to the stability in the region after the stationing of the Roman army at Emmaus in 68 CE, as related by Josephus (War IV, 445–446). After the second century CE, no evidence of construction was found inside the village.

BURIALS. Two main burial grounds were located to the south and east of the site, at a distance of about 100–200 m from it. The individual burial complexes, which were not excavated, could be identified by their outer form, consisting of a quadrilateral outer courtyard cut in bedrock, with a small square opening leading to a burial cave in at least one of the sides of the courtyard. The location of the tombs, their proximity to the Jewish village, their construction in the style characteristic of Jewish burial caves in the Second Temple period, and their attribution, on the basis of sherds found nearby, to the Late Hellenistic and Early Roman periods, all indicate that the burials belonged to a cemetery of the Jewish village of Umm el-‘Umdan.

CONCLUSIONS

Three phases were identified in the synagogue of Umm el-‘Umdan; these phases are referred to as buildings 1–3. Building 1, which dates to the Hellenistic–Seleucid period (the late third–early second century BCE), was designed as a quadrilateral broad house, probably for some public function. In the second phase, dated to the Late Hellenistic (Hasmonean) period (the late second and first century BCE), the hall of the previous period was widened and converted into what the excavators suggest was a synagogue (building 2); its entrance was relocated to the east and benches were constructed along three walls. In the third phase, dated to the Early Roman period (from the time of Herod in the second half of the first century BCE to the Second Jewish Revolt in the second century CE, or somewhat later) the synagogue hall was widened again (building 3); two rows of pillars were set along the hall, probably to support the roof or an upper story, and stepped benches were constructed along all four walls. These finds provide archaeological evidence for the development and existence of synagogues in Jewish rural settlements beginning with the Hasmonean period. The synagogue maintained a quadrilateral, broad-house plan, was entered from the east, and was designed to focus the attention of the congregation toward its center.

The excavators have suggested that Umm el-‘Umdan be identified with the early village of Modi‘in, based on the findings from the excavation, which accord well with information obtained from early historical sources on the nature and location of Modi‘in. The Jewish village was founded in the (pre-Hasmonean) Hellenistic period, and was inhabited without interruption through the Hasmonean and Early Roman periods, at least up to the Second Jewish Revolt. The synagogue is evidence of the village’s size, importance, and position among the settlements of the area. It was located between the hill country and the Shephelah, near an inland Roman road leading from Lod to Jerusalem. Settlements appearing on the Medeba map around Modi‘in that can be identified in the vicinity of Umm el-‘Umdan include Jerusalem, Emmaus (Nicopolis), Lod (Diospolis), Bethoron, Kapheruta, Adita (Tel

ALEXANDER ONN, SHLOMIT WEKSLER-BDOLAH

INTRODUCTION

Khirbet Umm el-‘Umdan, located within the municipal boundaries of Modi‘in, was first described by C. Clermont-Ganneau after a visit in 1873, then by C. R. Conder and H. H. Kitchener in their Survey of Western Palestine in 1883. From 2000 to 2003, prior to the construction of a new neighborhood in Modi‘in, excavations were conducted south of the ruin by A. Onn and S. Weksler-Bdolah on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The finds revealed that the ancient site extended over an area of about 6 a. and was established in the Hellenistic period, at the end of the third or beginning of the second century BCE, then occupied continuously at least until the Second Jewish Revolt. The site, with lanes, buildings, a synagogue, and a mikveh, was identified as a Jewish village. Remains of buildings and agricultural installations from the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods (sixth–tenth centuries) overlay the Jewish village. The latest remains uncovered were graves from the Late Islamic period and a lime kiln that had been dug into the buildings, causing considerable damage.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD. Two structures on the site—buildings 1 and 5—date from the end of the third to the beginning of the second century BCE. They were connected by lane 1. Building 1 consisted of a rectangular hall (7 by 3.80 m) surrounded by a fortified courtyard, from which a narrow corridor led into the hall. The corridor, which was L-shaped, extended along the southern and western sides of the hall to the main entrance in the middle of the long western wall. The floor of the hall was of beaten earth; on its northern side it was of leveled bedrock. Two partly preserved installations were cut into the bedrock: one, with a round opening (0.5 m in diameter), apparently served as an underground storeroom; the other, carved into the bedrock floor in the northern part of the hall and integrated within the northern wall, was in the shape of a rectangular niche (0.8 m wide, 0.4 m long, height unknown). The date of the hall could be established on the basis of six Seleucid coins of Antiochus III and Antiochus IV Epiphanes and of sherds recovered from the floors of the hall and courtyard and on the lane to the south. The function of the building in this period could not be determined. It may have been a public building, as suggested by its plan of a single central space with a long entrance corridor providing indirect access to the building. This view is corroborated by the fact that the public building identified by the excavators as a synagogue, which was built superimposed over the hall, was of a plan dictated in design and form by the hall itself.