Yattir, Khirbet

INTRODUCTION

Khirbet Yattir is located in the southern Judean Hills, about 12 km northwest of Arad. The ancient name is preserved in the tomb of Sheikh el-‘Atiri on the summit of the hill. The identification of the site as Yattir, first suggested by the medieval traveler Ashtori Haparchi and much later by E. Robinson, is universally accepted. Prior to excavation, the remains of walls and vaults were visible on the surface, and four large stone columns and part of an apse belonging to a church were visible on a spur to the south of the site. The ancient houses encircle the eastern side of the hill, forming a crescent shape. Almost every house had an open courtyard with a cistern and access to caves that were used for dwelling and storage purposes. Wells at the foot of the eastern slope provided a perennial source of water for the inhabitants. Fourteen ancient winepresses have been identified near the site and four olive-oil presses within it, indicating, despite the semiarid climate, that during the Hellenistic to Byzantine periods the inhabitants cultivated grapes and olives.

Yattir is mentioned four times in the Hebrew Bible, suggesting that it was inhabited during the seventh century BCE. Furthermore, I Samuel 30:27 relates that David sent spoils taken from the Amalekites to Yattir. If this passage is historically accurate, it would provide evidence that Yattir was inhabited as early as the tenth century BCE. Eusebius, in his Onomasticon of the fourth century CE, described Yattir as a “large Christian village.” Yattir is also depicted on the sixth-century CE Medeba map.

Five brief seasons of excavation were conducted at Yattir in 1995–1999 by H. Eshel, J. Magness, and E. Shenhav under the auspices of Bar-Ilan University and the Jewish National Fund. The excavations focused on four areas: area A at the top of the hill, area B on the eastern slope of the hill, area C on a spur to the south of the site, and area D on the northern slope near the summit of the hill.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE EARLIEST SETTLEMENT TO THE SECOND JEWISH REVOLT. The earliest remains at Yattir date to the Chalcolithic period and the Early Bronze Age. Fragments of cornets and hole-mouth jars were discovered in the area of two natural caves on the eastern slope (area B). These caves were sealed by layers of fill deposited in the Byzantine period, when structures were constructed above. The earliest settlement at Yattir was presumably located on the summit of the hill, the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age sherds having washed down the slope. Alternatively, these vessels may have accompanied burials inside the caves, although no evidence of burials was found.

After a long gap in occupation, Yattir was resettled in the Iron Age. Scattered sherds of this period were discovered in area D, probably belonging to an Iron Age citadel on the summit. In area B, a few Iron Age walls were uncovered together with a ceramic assemblage dating to the seventh century BCE, including cooking pots with a vertical rim and stamped geometric designs on the handles. Houses were apparently built on the lower eastern slope of the hill at this time, close to the wells. However, most of the Iron Age sherds found in the excavations originate in the fill that covered the caves in area B. No Iron Age sherds antedating the seventh century were recovered.

Fragments of Persian period pottery were also discovered in the layers of fill in area B, including a number of imported black-glazed sherds dating to the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. A small silver coin from the fourth century, apparently minted in Gaza, was found on the summit of the hill. A large quantity of Hellenistic pottery was recovered in the excavations and a lead sling stone was discovered on the western slope of the hill. Several walls that appear to have been built in the first century BCE were uncovered on the summit (area A), perhaps belonging to a citadel or fortress.

The nature of settlement at Yattir changed after the Hellenistic period. The top of the hill was abandoned and the Roman period settlement was located on the eastern slope, above the wells. No information was recovered concerning Yattir in the Hasmonean or Early Roman periods, although fragments of limestone vessels found in the excavations indicate that at least some of its inhabitants were Jews who observed purity laws. The latest finds from the fill in area B date to the first century CE and include coins of Agrippa I and the First Jewish Revolt.

The skeleton of a woman was discovered in a natural cave under the church in area D, accompanied by an assemblage of pottery vessels characteristic of the period of the Second Jewish Revolt. This appears to have been a refuge cave during the revolt, and the finds suggest that Yattir was destroyed at the end of that revolt.

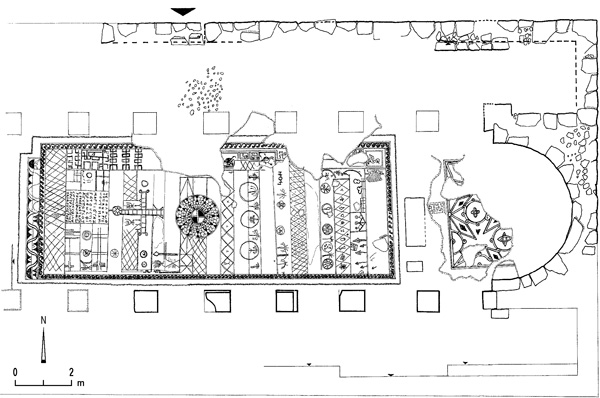

THE BYZANTINE PERIOD. The church excavated in area C lay outside the Byzantine period settlement. A large reservoir was located in the area between the church and the settlement, fed by rainwater brought by channels. Excavations have exposed almost the entire church, which measures 24 by 13 m. The main hall was divided by two rows of six columns into a nave flanked by aisles. The columns stood on pedestals, no two alike. Of the five pedestals found, three supported columns with round bases, two supported columns with polygonal bases (seven-sided and eight-sided, respectively).

Two Corinthian capitals with carved Maltese crosses were found in the church. The other four capitals were reused Nabatean capitals, apparently taken from an unknown first-century CE building at the site. The floors of the church were decorated with mosaics. A simple crowstep pattern covered the floor in the aisles. A depression or sump in the mosaic floor in the northwest corner of the hall probably held a jar for foot-washing. The floor of the apse was decorated with a geometric mosaic. In the nave of the main hall, measuring 13 by 5 m, two phases can be distinguished in the mosaic floor. The earlier floor was of good quality, comprising a design of grapevines that form medallions containing birds. Four birds and a few bunches of grapes are preserved. A strip by the western entrance was decorated with a rosette design, a running wave pattern, and a meander.

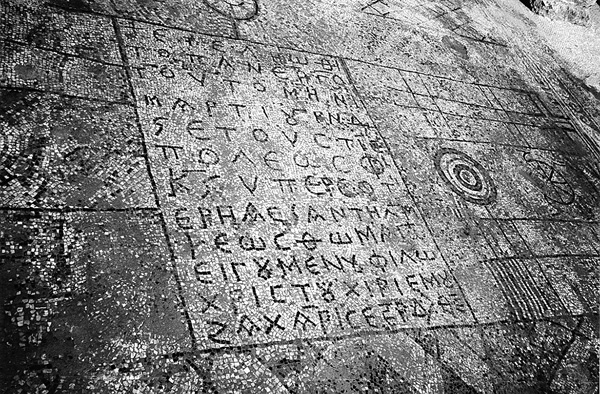

The later mosaic floor is described here from west to east, beginning with the entrance from the narthex and moving towards the apse. A row of rhomboids decorated the western side, between rosettes and an inscription (see below). To the south of the inscription were magical designs, while portions of the earlier floor were preserved to the north of the inscription. To the east of the inscription a large cross above a circle is depicted, apparently representing Golgotha. The cross was flanked by magical symbols. To the east of the cross, the center of the floor was decorated with a large circle containing geometric whirled spokes with a cross in the center. The area between the large circle and the apse was divided into eleven strips decorated with geometric and magical designs. The uppermost strip, just below and in front of the steps leading to the bema, contained a schematic depiction of a building with a gabled roof and three hanging lamps. The inscription in the nave is 12 lines long, and reads “This work was completed in the month of March in the sixth indiction, year 526 of the era of the city, for the benefit of the salvation and the aid of Thomas the most holy, abbot of the monastery. [The work was done] by my hands, Zacharis, son of Yeshi, the builder, servant of God.”

This inscription and the inscription in the atrium (see below) indicate that this was a monastic church. Since this inscription is dated according to the calendar of Provincia Arabia, which began when Rome annexed the Nabatean kingdom in 106 CE, the laying of the later floor dates to 631/632 CE. The city mentioned in connection with the date is probably Elusa.

Fragments of a square ceramic lantern or censer decorated with incised palms were found on the floor of the church. Thousands of roof tile fragments and dozens of iron nails recovered inside the church indicate that it had a tiled, gabled roof supported by wooden beams.

The narthex of the church was decorated with a white mosaic floor, in the center of which was a medallion containing a cross. An underground cistern was located in the middle of the atrium, with two depressions or sumps in the floor next to it. On the eastern side of the atrium, by the entrance to the narthex, was a six-line Greek inscription within a double frame: “All of the work in building the church including the mosaic was carried out in the time of Yochanan [John] ben Zachariah, who honors God, the diacon, the head of the monastery, during the month of May in the ninth indiction in the year 483 according to the city’s calendar.”

If this inscription uses the same calendar of Provincia Arabia as the inscription in the nave of the church, it would date to 588/589 CE. However, this creates a two-year discrepancy with the indiction mentioned. As no correspondence has been found between the ninth indiction and the year 483 in the calendar of any other city in the region, the date of 588/589 CE is apparently correct, and the inscription commemorates the laying of the earlier floor in the church, that is, the floor decorated with grapevine medallions framing birds.

At the top of the northeast slope (area D), parts of another, less well-preserved church were excavated. Excavations in this area began after an unusual Corinthian pilaster capital was discovered lying on the surface. In addition, houses below this area had incorporated reused marble columns and two pedestals. The eastern part of the church had washed down the slope, and therefore it was impossible to determine the original length of the building, although the main hall was over 12 m long. Portions of the northern and southern walls were excavated and two stylobates were uncovered, which divided the main hall into a nave, 12.5 m wide, and aisles, 2 m wide each. Columns with pedestals stood on the stylobates. The surviving walls indicate that the church was not oriented to the east, but deviated about 40 degrees to the southeast. This peculiar orientation may be due to the limited size of the terrace on which the church was built. The western half of the church was better preserved, as it was buried under deep accumulations near the top of the slope.

The mosaic floor was made of colored tesserae measuring 1 by 1 cm. Most of the images were destroyed following the Muslim conquest, when the church was used for domestic purposes. The only surviving image is that of an eagle facing right in the northwestern corner of the nave. A matching eagle facing left was presumably located in the southwestern corner. Some geometric designs are preserved along the edges of the nave, similar to the designs that encircled the floor of the nave of the monastic church in area C. At some point, the colored mosaic floor was replaced with a plain white mosaic made of larger tesserae (2 by 2 cm). Opposite the entrance from the narthex into the southern aisle, a complete four-line Greek inscription framed within a tabula ansata was uncovered: “In the days of the most holy Bishop Theodoros and Sabinios the Presbyter, all of the work on the mosaic was done [by] Absobo and Jonathan and Jeremiah in the fourteenth indiction.” Since the bishop Theodoros and Sabinios the Presbyter are unknown, this inscription cannot be dated. In the Early Islamic period the inscription was covered over with plaster.

The atrium and narthex were paved with a white mosaic floor. The atrium had a stylobate on top of which was a Corinthian pilaster capital, similar to the one discovered on the surface prior to excavation. Similar capitals decorated the crypt of a church in Hermopolis Magna (modern el-Ashmunein) in Egypt, suggesting that the pilaster capitals at Yattir may have originated in a crypt below the church of area D.

A capital decorated with an unusual conch shell motif was discovered in secondary use in a room constructed to the south of the church after the Byzantine period. In the Early Islamic period, a cistern was dug into the narthex of the church; a Corinthian capital was found in secondary use in the stone vault covering the cistern. In the Mameluke period, the opening of the Byzantine cistern in the atrium to the west of the church was raised to the contemporary ground level. Architectural elements originating from the church and incorporated into the new construction include parts of three columns, two Corinthian capitals, and a stone with an incised cross.

THE MAMELUKE PERIOD. On the eastern slope of the hill (area B) excavations focused on a structure that some scholars had identified as an ancient synagogue. Internally it consists of a single room, 7.5 by 6.5 m. Its walls are c. 1.5 m thick, preserved to a height of c. 3 m. The entrance was through an 80 cm-wide doorway in the northern wall, approached from the north by a road paved with stone slabs. What appeared at first to be another doorway in the southern wall turned out to be a curved (concave)

HANAN ESHEL, JODI MAGNESS, ELI SHENHAV

INTRODUCTION

Khirbet Yattir is located in the southern Judean Hills, about 12 km northwest of Arad. The ancient name is preserved in the tomb of Sheikh el-‘Atiri on the summit of the hill. The identification of the site as Yattir, first suggested by the medieval traveler Ashtori Haparchi and much later by E. Robinson, is universally accepted. Prior to excavation, the remains of walls and vaults were visible on the surface, and four large stone columns and part of an apse belonging to a church were visible on a spur to the south of the site. The ancient houses encircle the eastern side of the hill, forming a crescent shape. Almost every house had an open courtyard with a cistern and access to caves that were used for dwelling and storage purposes. Wells at the foot of the eastern slope provided a perennial source of water for the inhabitants. Fourteen ancient winepresses have been identified near the site and four olive-oil presses within it, indicating, despite the semiarid climate, that during the Hellenistic to Byzantine periods the inhabitants cultivated grapes and olives.

Yattir is mentioned four times in the Hebrew Bible, suggesting that it was inhabited during the seventh century BCE. Furthermore, I Samuel 30:27 relates that David sent spoils taken from the Amalekites to Yattir. If this passage is historically accurate, it would provide evidence that Yattir was inhabited as early as the tenth century BCE. Eusebius, in his Onomasticon of the fourth century CE, described Yattir as a “large Christian village.” Yattir is also depicted on the sixth-century CE Medeba map.