Yodfat

INTRODUCTION

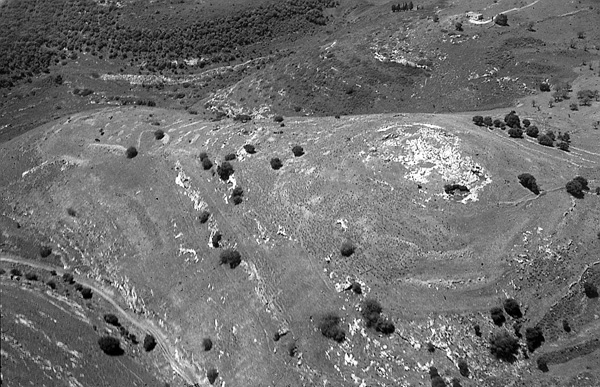

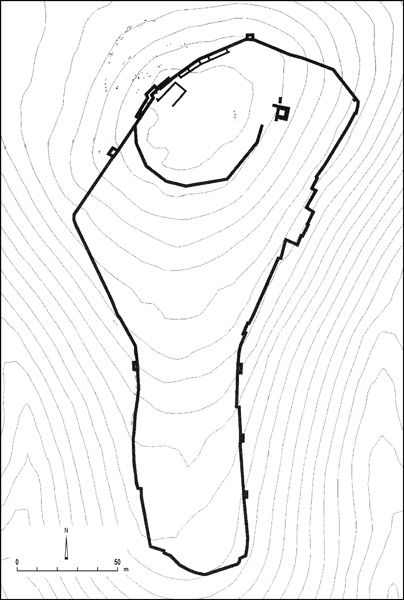

Yodfat (Jotapata) is located in the western Lower Galilee near the modern Moshav Yodfat, 3 miles north of Sepphoris. The town was built on an isolated hill with a rounded summit and a narrow ridge to the south, surrounded on three sides by deep ravines; on the north it is connected to Mount Miamin by a shallow saddle. On the bare bedrock of the summit are rock-cut cisterns and signs of quarrying activity. The eastern slope of Mount Miamin is inhabited by the ruins of Khirbet Jifat, the Arabic name preserving the ancient name of Yodfat.

Josephus Flavius first mentioned Jotapata as one of the towns in the Galilee fortified by him at the beginning of the First Jewish Revolt. He later described the attempt by the Roman army to take Jotapata in the first battle of the revolt and the 47-day siege of the fortified town. The site is also mentioned in the Mishnah, in the list of “fortified towns from the time of Joshua Bin-Nun,” where “…old Yodfat…” would seem to imply that there was also a new Yodfat. The site is referred to again in the Talmud and in the list of the “Priestly Courses” as the home town of the Miamin Course.

Yodfat was first identified in 1847 by E. G. Schultz, based on the name of the Arabic ruins, the site’s topography and location, and the lack of natural water sources. Modern scholars agree with the identification, and pottery from the Hellenistic, Early Roman, Late Roman, and Byzantine periods collected in surveys (prior to excavations) further supported this conclusion. In 1976, E. Meyers and his team conducted a survey at the site and uncovered a cooking pot at the foot of the northern town wall, which they dated to the Early Roman period, suggesting that the wall should be assigned to the First Jewish Revolt. From 1979 to 1991, numerous small-scale surveys conducted by M. Aviam yielded interesting results, including the identification of large segments of the town wall, a residential area on the eastern slope, and an olive-oil press in a cave. In 1989, a short excavation was carried out in the press, yielding pottery dating no later than the mid-first century CE. An extensive survey conducted by M. Aviam and D. Adan-Bayewitz in 1991 provided evidence that the upper site (the hill and the ridge) dates to the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods, while the lower area of Khirbet Jifat dates to the Late Roman, late Byzantine, and Mameluke periods.

The first season of excavation took place in 1992, directed by M. Aviam, D. Adan-Bayewitz, and D. Edwards on behalf of the University of Rochester, Bar-Ilan University, the University of Puget Sound, and the Israel Antiquities Authority. The last four seasons (1995–1997, 1999) were directed by M. Aviam for the University of Rochester and the Israel Antiquities Authority. The excavations extended over the entire site (about 12.5 a. within the town walls).

EXCAVATION RESULTS

THE EARLY SETTLEMENT. In three areas on the summit, remains of a third- to second-century BCE settlement were uncovered, including small rooms and floors. On two of the earliest floors and other loci, the recovered ceramic assemblage included an imported Greek amphora with a stamped handle dating to 145–135 BCE, two Galilean-type pithoi named by the excavators Galilean coarse ware, local “Phoenician” jars, and oil lamps, two of which were decorated with cupids. This stratum was destroyed and covered with a thick layer of ash. It appears that the village antedating the Hasmonean conquest was inhabited by a gentile population.

THE FORTIFICATIONS. Two main fortification systems were revealed at the site. The earlier, with two phases, surrounded the summit of the hill. The northern wall, guarding the only accessible approach to the town, was built of two parallel, massive walls. In the second phase two large towers were added along this side. This phase is dated to the Late Hellenistic period, superimposed upon the earlier Hellenistic rooms mentioned above. A Hasmonean coin found in the foundations suggests that these walls were erected after the Hasmonean takeover of the Galilee at the end of the second century BCE.

The later fortification wall, erected in the Early Roman period in preparation for the impending Roman invasion, adjoins the earlier wall on the northeast and west and surrounds the entire town. On the northern side it probably incorporated some segments of the earlier wall as well; where this wall was missing, a casemate wall was built. Some parts of the new wall were solid and c. 1.2 m wide, others were built as a casemate of varying width. At the wall’s northeastern corner, it curves sharply to the north and climbs up the steep slope to meet the earlier wall around the summit. Square towers were built along the wall at spots of topographical vulnerability. On the west it rests upon the foundations of an Early Roman period house. In one of the smallest rooms of the casemate wall an underground rock-cut shelter was uncovered, comprising a short (1 m) shaft with a closing mechanism, leading into a vertical tunnel (5 m long) that opened onto three rooms in two stories. Storage jars and 12 silver coins from the reign of Nero were found there. On its southeastern side, the wall cut through a pottery kiln, the remains of which had been dumped nearby. In and around the kiln were wasters of vessel types that were also found in the destroyed houses of the town. It is thus evident that the kiln was in use until it was torn down for the erection of the wall, prior to the war and the destruction of the entire town.

THE RESIDENTIAL AREAS. Three residential areas were excavated on the eastern and one on the northeastern side of the hill. Parts of terraced houses, simply built of fieldstones and probably covered with mud plaster, were uncovered on the steep slope within the northeastern corner of the fortification wall. The floors were of leveled rock or beaten earth, or, in the case of one room near a cistern, of untrimmed stone slabs. In two houses, plastered, stepped pools were found, identified as ritual baths (mikvehs). One of the rooms in this northeastern quarter was unique in that three of the walls were covered with frescoes in what seems to be the Second Pompeian style, while the floor was also frescoed in a design of red and black tiles. Excavation of this building was halted to avoid further damage until the site and the frescoes can be properly preserved.

THE POTTERY WORKSHOPS. On the southeastern side of the town, three pottery kilns were excavated. Two kilns probably belonged to a potter’s workshop that produced cooking pots similar in design to the vessels from Kefar

THE FINDS. Typical first-century CE pottery vessels such as cooking pots, jugs, bowls, and storage jars, many locally made, were found on the floors of the houses. The most common oil lamp at the site was knife-pared, including black and multi-nozzled types. Other finds include over 100 sherds of soft limestone cups and bowls, one small complete pitcher, and some 200 pyramidal clay loom weights. Ten of the loom weights were found in situ on a floor together with the remains of the roof. Such a large number of loom weights suggests the importance of weaving in the commercial life of this community. The very few luxury finds include two engraved gems from rings, remains of glass vessels, and some carved bones. The paucity of luxury items should not necessarily be attributed to the poverty of the town inhabitants, but rather to looting by the conquering Roman troops. An unusual find is a complete 20 cm-long iron door key, similar to those found in the Judean Desert caves.

The numismatic evidence is of interest. The latest coins date to the reign of Nero. These were found together on the same floor with Hasmonean coins, implying that Hasmonean coins were still in circulation among the Jewish communities in the Galilee until the First Jewish Revolt. No coins of the First Jewish Revolt were found, not even the type found and probably minted at Gamala. This supports Josephus’ assertion that Yodfat was the location of the first battle with the Romans, leaving no time to mint coins there.

THE ASSAULT RAMP. According to Josephus’ description, the Romans erected an assault ramp on the northern slope of the town. Two soundings were carried out on the northern slope, where a number of chunks of mortar containing crushed pottery had been discerned. The excavation revealed a c. 1 m-deep layer of red-brown soil and many fieldstones, on top of which was a mortar layer (not a continuous surface). Dozens of iron arrowheads and catapult bolts were found in these two layers, some of which had banded tips or tangs. Two tiny nails of a Roman army shoe (caliga) and a large rolling stone were also retrieved in the layers. All these finds suggest that the layers of mortar and soil with stones are the remains of the Roman assault ramp constructed during the battle. This ramp is quite different from that known from Masada, as here there was no need to build a high ramp, but one which would only cover the slope and create a moderate grade to accommodate movement of the siege engines.

THE WEAPONS. Over 60 arrowheads were found during the excavations—18 in the two squares excavated on the northern slope, 26 in the soundings along the northern fortifications, and 27 in the residential areas, including 5 in the frescoed room. Most are of the common iron trilobate type (weighing c. 5 gm); two are of the bodkin type with square cross-section. Approximately 15 catapult bolts were found throughout the site—2 along the fortifications and 11 in the residential areas, most on floors. They were found in various sizes, ranging from 8 to 15 cm long and from 20 to 30 gm in weight. Some 35 ballista stones were discovered, occurring in almost every excavated area. They were all fashioned from local limestone with a pointed chisel. The largest is 23 cm in diameter and 2 kg in weight, the smallest 15 cm in diameter and 0.65 kg in weight. The tip of a Roman-army style iron dagger was found in the northeastern area. An iron spear-butt was retrieved near the northwestern wall, but its association with the Early Roman level is uncertain. A few iron hobnails associated with Roman army footwear, 1 cm long with mushroom-like heads, were found along the northern wall and within the assault ramp. Various bronze fragments and one silver piece can also be associated with Roman army equipment.

THE HUMAN REMAINS. Josephus (War III: 336–338) describes the bloody end of the siege and the conquest of the town in this manner:

“On that day the Romans massacred all who showed themselves; on the ensuing day they searched the hiding-places and wreaked their vengeance on those who had sought refuge in subterranean vaults and caverns, sparing none, whatever their age, save infants and women. The prisoners thus collected were 1,200; the total number of dead whether killed in the final assault or in previous combats, was computed at 40,000.”

Human remains at Yodfat present a much different picture than that emerging from other excavated sites. During excavation of the olive-oil press cave, a few human bones were found, some of which were burnt. In field XI, at the bottom of a cistern, a collective burial was found, comprising the remains of two adults and a child surrounded by a low wall of fieldstones. In the upper level of another cistern, a few human bones were uncovered. On the floor of the “frescoed room,” bones of an adult male were found together with some arrowheads. In a large cistern in a residential area of field XI, the top of a thin wall, one row wide, was discerned encircling an area of 3 by 1.5 m along the western plastered wall of the cistern; the enclosed area contained the bones of about 20 individuals—12 adults (4 females, 8 males) and 8 children. Preliminary studies indicate evidence of trauma to some of the bones. As the cistern was not completely excavated, it is possible that it contained the remains of additional individuals. The finds from the fill of the cistern included pottery which cannot be dated to later than the mid-first century CE, as well as a heavy ballista stone and various everyday artifacts.

It may be that the bodies of the slaughtered inhabitants of Yodfat were left unburied for over a year until Jews returned to the town, gathered the bones from the streets, courtyards, and destroyed houses, and buried them in cisterns and caves. In some cases, low walls were erected around the gathered bones, and in others, the cisterns were then filled up with soil and stones from the destroyed houses.

There is no doubt that Josephus greatly exaggerated the number of dead. According to the size of the site, the population of Yodfat can be estimated to have been approximately 1,500–2,000. If some 5,000 refugees fled into the walled town from neighboring villages, there may have been around 7,000 people in Yodfat at the beginning of the siege. Josephus’ number of 1,200 captives appears sound; thus several thousand were probably killed in the actual battle along the northern wall and in the final conquest and massacre, or died of hunger and disease.

THE ETCHED STONE. In square Q17 of field XI, a small (11-by-8 cm) flat fieldstone was found bearing sketches on both sides, lightly scratched with a pointed tool. On one side is a depiction of a building with a gabled roof built on a podium of three steps, with a small tree on one side of the roof and a harp on the other. There is little doubt that this is a representation of a mausoleum, similar to incised depictions of mausolea on Jewish tombs and ossuaries in Judea from the first and second centuries CE. The trees may symbolize the “tree of life” or actual trees standing beside a tomb. On the other side of the stone is an abstract representation of cancer, the zodiac symbol of the Hebrew month of Tamuz (July). The author’s interpretation of this stone is that it graphically depicts the fear of approaching death of one of the besieged Jews in the town, the mausoleum representing death, and the zodiac symbol, the time of year. Simply put, the stone may be understood as conveying the meaning: “I will die in July.” Yodfat fell on July 20, the first day of Tamuz.

CONCLUSIONS

Josephus’ story of the battle of Yodfat is one of the most detailed descriptions of the First Jewish Revolt. This may be due to the fact that, as commander of the Jewish forces, he felt the need to rationalize the defeat and fall of the town into Roman hands by vividly describing the horrors of the war. Excavations at the site have actually substantiated much of Josephus’ narrative. First, the remains attest that there was a heavy battle around the mid-first century CE on the hill of Yodfat, fought by the Jewish defenders (represented by ritual baths, stone vessels, a Jewish inscription, and Hasmonean coins) and the Roman army (which left catapult bolts, ballista stones, and nails of caligae). Second, the town was surrounded by a fortification wall hurriedly constructed in the Early Roman period, and reinforced during the war. Third, Roman earthwork was erected on the northern slope of the town. Fourth, arrows and ballista stones were shot into the town from all directions. Fifth, many of the citizens of the town died during the war and conquest. Sixth, the town was burnt down and demolished after a battle. Seventh, bones collected into empty cisterns and human bones on floors of houses and surrounded by arrowheads present a lucid picture of the town’s violent end. And eighth, the latest coins on the floors of the rooms and in the underground shelter enable a dating of the destruction of the town to Vespasian’s military campaign.

The excavation at Yodfat has shed additional light on first-century CE Galilee. Previously, knowledge of this period derived from relatively few loci in small villages such as Capernaum and Nazareth and sporadic remains from two Galilean cities—Tiberias and Sepphoris. The evidence of everyday life at Yodfat is very similar to the finds from Gamala, though final processing and further research will certainly reveal some degree of regional differences between the two towns. The artifacts from the battle itself are also very similar to those uncovered at Gamala, although further analysis of the finds from the two sites may uncover differences in the types and amount of military equipment used at each, representing the differing circumstances described by Josephus. A similar explanation can be proposed for the lack of human remains at Gamala. In contrast to the end of the battle at Yodfat, when people were slaughtered in houses and caves and pushed down the steep sloping streets to their death, the citizens of Gamala fled uphill and defended themselves from the hilltop. According to Josephus, some of the people were killed at this point, while others were killed or committed suicide on the steep natural cliffs to the north.

MORDECHAI AVIAM

INTRODUCTION

Yodfat (Jotapata) is located in the western Lower Galilee near the modern Moshav Yodfat, 3 miles north of Sepphoris. The town was built on an isolated hill with a rounded summit and a narrow ridge to the south, surrounded on three sides by deep ravines; on the north it is connected to Mount Miamin by a shallow saddle. On the bare bedrock of the summit are rock-cut cisterns and signs of quarrying activity. The eastern slope of Mount Miamin is inhabited by the ruins of Khirbet Jifat, the Arabic name preserving the ancient name of Yodfat.

Josephus Flavius first mentioned Jotapata as one of the towns in the Galilee fortified by him at the beginning of the First Jewish Revolt. He later described the attempt by the Roman army to take Jotapata in the first battle of the revolt and the 47-day siege of the fortified town. The site is also mentioned in the Mishnah, in the list of “fortified towns from the time of Joshua Bin-Nun,” where “…old Yodfat…” would seem to imply that there was also a new Yodfat. The site is referred to again in the Talmud and in the list of the “Priestly Courses” as the home town of the Miamin Course.