Whence-a-Word?: An Eye for an Eye

The phrase “an eye for an eye” describes a type of retributive justice. Known in legal circles as lex talionis, or “the law of retaliation,” it stipulates that a punishment or compensation be commensurate with the crime committed or damage caused.

The expression entered our parlance through the Hebrew Bible, where this principle of natural law appears in the Book of Leviticus: “Anyone who maims another shall suffer the same injury in return: fracture for fracture, eye for eye, tooth for tooth” (Leviticus 24:19–20; cf. Exodus 21:23–25 and Deuteronomy 19:21). Because talionic laws are rooted in the legal traditions of the ancient Near East, modern scholars have assumed that the Bible borrowed this tit-for-tat principle from the Laws of Hammurabi—the famous Babylonian code of law from the 18th century BCE.

But there is a difference. Hammurabi’s laws apply lex talionis only to injuries to a full citizen, whereas injuries done to animals and people of lower social status called for monetary compensation. In contrast, the Hebrew Bible makes a clear distinction between the value of animal lives and that of all humans, including the enslaved (Leviticus 24:21).

Since the recovery of Hammurabi’s laws in 1901, parallel codes from the second millennium BCE have been found around the ancient Near East: the Laws of Ur-Nammu, the Laws of Lipit-Ishtar, and the Middle Assyrian laws. In 2010, two pieces of a cuneiform legal tablet were found at the site of Hazor in northern Israel.a Known today as the Laws of Hazor, the fragments of seven laws concern compensation for damage to an enslaved person, showing that some aspects of biblical law were present in Canaan already in the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000–1550 BCE).

Although the biblical version of lex talionis was fairly progressive in curbing excessive vengeance in favor of proportionate justice, Jesus in his Sermon on the Mount seems to be revoking this ancient law: “You have heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you, Do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also” (Matthew 5:38–39). Some argue Jesus said this hyperbolically, as he was calling his followers to a higher standard of righteousness. Alternatively, Jesus did not demand that his followers ignore retribution, only that they bear it themselves. Such an ethic commends suffering an injury twice rather than paying back and taking “an eye for an eye.”

The Hidden Hands Behind the New Testament

When we imagine the authors of the Bible, we tend to picture solitary prophets and apostles—Paul hunched over a scroll, perhaps, or an evangelist illumined by divine inspiration. What we do not envision, much less credit, are the enslaved secretaries, scribes, and couriers who took dictation, edited manuscripts, and transported letters across the Roman Empire. Yet without these individuals, the New Testament quite literally would not exist.1

The early Christian movement emerged within an imperial system structured by and dependent upon slavery. Literacy was rare, and among those who could read or write, few had the skill, training, or leisure required to compose long letters or theological treatises. As with other facets of elite Roman life, the work of writing was frequently delegated to enslaved professionals. Enslaved people were trained as scribes, copyists, and administrative assistants—roles indispensable to both public and private communication. Despite Christianity’s apparent social radicalism, in this respect, the early church was no exception.

Consider Paul’s letter to the Romans, arguably the theological centerpiece of the New Testament. Although Paul is traditionally regarded as the sole author, Romans 16:22 offers a startling admission: “I, Tertius, the writer of this letter, greet you in the Lord.” Tertius is not a rhetorical device or spiritual metaphor; he is the person who physically penned the letter. His name—Latin for “Third”—reflects a common practice of designating enslaved individuals with solitary numerical or utilitarian names. Nor was this collaboration unique. In Galatians 6:11, Paul draws attention to the large letters written “with my own hand,” implicitly distinguishing those few lines from the rest of the letter. Similar notices appear in 1 Corinthians 16:21 and Colossians 4:18.

These individuals were not mere machines mechanically transcribing dictated speech. In antiquity, taking dictation was a practiced skill, and secretaries often played interpretive roles. They smoothed syntax, emulated the voice of their master, made editorial choices, and sometimes altered content. The shorthand they used was itself an ambiguous writing system that was legible only to the enslaved and formerly enslaved workers who spent years learning the craft. Classical scholars and papyrologists have noted that enslaved scribes occasionally inserted marginalia and humorous interjections into the texts they copied. Corrections, of course, were a standard part of their work. Improving the words of the masterly author was part of the remit of the enslaved literary worker. Their roles were so critical that Cicero lamented that without his enslaved secretary Tiro, “my work is silent” (Letters to Friends 16.10.2).

The implications are far-reaching. If enslaved individuals composed, copied, and preserved Christian texts, they were not passive transmitters of scripture but active contributors—interpreters, editors, and, in many cases, theologians. Their labor was not only manual but also intellectual. Although their names and stories were often omitted or suppressed, traces of their presence remain embedded in the textual tradition.

This erasure was neither accidental nor apolitical. Roman critics of Christianity like Celsus frequently derided it as a religion of “women and slaves”—a stigma in a society that prized elite male authority. As the church gained cultural and political power, some of its early enslaved collaborators were posthumously rebranded. Figures such as Mark, traditionally identified as Peter’s interpreter, and Onesimus, the enslaved man mentioned in the Letter to Philemon, were transformed in later tradition into bishops, martyrs, and saints. Their servile origins were quietly erased. Even Mary, the mother of Jesus, underwent this form of theological redressing. In Luke’s Gospel, she refers to herself as the doulē of the Lord—a term meaning “enslaved woman.” Yet most English translations dilute this to “handmaid” or “servant,” a choice that obscures her original social context.

The Pauline epistles and Book of Acts similarly depict Paul surrounded by a rotating cast of aides—Epaphroditus, Tychicus, Fortunatus—whose names (often derived from adjectives like “Lovely,” “Lucky,” or “Useful”) were common among enslaved populations. Despite this, Christian tradition typically remembers these figures as freeborn companions or enthusiastic volunteers.

The anonymity of such figures speaks volumes. Ancient sources rarely name the people who physically produced or transported documents. When Pontius Pilate “writes” the inscription on Jesus’s cross in John 19:19, it is highly unlikely that he painted the words himself. After all, there’s no good reason to think that Pilate could speak or write in Hebrew. More plausibly, an enslaved scribe or artisan performed the task. Yet we do not ask who that person was, because the literary tradition and our own constructions of authorship have taught us to ignore the labor behind the text.

The success of early Christianity depended on these invisible collaborators. In the ancient world, letter-writing was no simple affair. Delivering a letter required a courier capable of making long and sometimes dangerous journeys, someone who could explain the contents upon arrival and read them aloud to the recipient community. In Christian settings, that often meant entrusting enslaved workers with the transmission of the words attributed to apostles and church leaders. These couriers were not simply messengers; they were oral interpreters and, at times, missionaries.

Once a letter reached its destination, enslaved scribes were responsible for copying it, preserving it, and sometimes compiling it with other texts. In scriptoria and private households alike, they copied gospels repeatedly, altered phrasing, clarified meaning, added glosses, and repaired or preserved scrolls using cedar oil and other materials. These practical decisions shaped the textual form and content of the Bible for generations.

Modern readers may balk at the notion that enslaved individuals helped to “write” scripture. Yet we readily accept that Paul dictated his letters, that Mark served as Peter’s interpreter, and that early Christian literature was the product of collaboration. Acknowledging this fact is not necessarily a threat to biblical authority. On the contrary, it testifies to a richer, more inclusive vision of inspiration—one that transcends social hierarchies. The same spirit that inspired Paul also worked through Tertius. The gospel is not diminished by the hands that wrote it; rather, it is deepened by their humanity. This recognition invites us to reclaim a central, often forgotten truth of Christian origins: Those on the margins have always been at the heart of the story.

Biblical Profile: Paul, the Bible’s Last Action Hero

In the Book of Acts, the apostle Paul is heroically recast as invincible to physical assaults and incapable of suffering either injury or pain. The blindness that afflicts him on the road to Damascus proves to be temporary and is followed throughout the book by several cycles of fast-paced, narrow escapes from hostile opponents and bodily harm (e.g., Acts 9:23–25; 14:5–6; 17:5–10).

When Paul arrives in Lystra, for example, he is caught by a hostile mob intent on stoning him and dragging his body out of the city (Acts 14:19–20); though he is presumed dead, in a surprising reversal of fate, Paul gets up and boldly walks back into the city, resuming his travels the very next day. Another instance late in the book describes a mob of more than 40 conspirators in Jerusalem who vow to taste no food until they have killed Paul, but he gets wind of the ambush and is aided in his escape by Roman officials (Acts 23:12–35). Finally, Paul survives a shipwreck completely unscathed (Acts 27) and, equally impressively, is unharmed by a viper’s bite on the island of Malta (28:3–6).

Acts uses these episodes of miraculous rescue as a primary means to cast Paul’s public image in heroic terms. This begins with his miraculous healing in Damascus (Acts 9) and continues until the very end of Paul’s story, which leaves readers in Rome (Acts 28), where the imprisoned Paul’s inviolable body makes him uninhibited by the restraints of arrest, and he remains invulnerable even to a fitting noble death. Even though Paul does not die, Acts foreshadows second-century martyr accounts, such as the Martyrdom of Polycarp, where heroes endure the most horrific tortures without ever crying out in pain. However, Acts takes it to a further extreme, representing Paul’s body as not only incapable of suffering pain, but immune to any bodily injury at all.

In addition to his invulnerability in Acts, Paul often takes on a supernatural aura, manifest through his miraculous touch as well as his gazing eyes and even the clothing he has worn, all of which carry the power to cast out sickness, disease, and evil spirits. Indeed, Paul’s miracles in Acts draw comparisons with other mediators of the divine. He is pitted against Peter, John, Stephen, Philip, Ananias, and Barnabas, though Paul is ultimately cast as their wonder-working superior simply by exceeding their miraculous feats in both type and sheer number. Likewise in competition with outsiders, Acts demonstrates Paul’s superiority as a wonder-worker through competitive showdowns with the Jewish prophet and sorcerer in Cyprus, the priests of Zeus in Lystra, and the seven sons of a Jewish high priest and miracle worker in Ephesus.

Miracles in Acts serve to identify Paul as a hero in body and action, operating in a legitimizing framework of explicit divine support. In his undisputed letters, on as many as five separate occasions, Paul himself refers to the “signs and wonders” that were performed in the communities to which he writes. In the opening lines of his very first letter, for instance, Paul rejoices over the assembly in Macedonia when writing, “For we know, brothers and sisters loved by God, that he has chosen you, because our gospel came to you not simply with words but also with power, with the Holy Spirit and deep conviction” (1 Thessalonians 1:4–5; italics mine). Though his references to his own wonder-working tend to be indirect and in passing, they seem to indicate that something more than just his rhetorical prowess was on display when he participated in the founding of the assembly. Strikingly similar expressions occur also in his letters to Corinth, Galatia, and Rome. This helps to explain, in part, how Acts comes to remember Paul as a miracle worker in the first place.

However, though Paul seems on occasion to remind others of the miracles he performed in their presence, it certainly is not a major point of emphasis in his apostolic self-representation. In his letters, Paul is much more interested in emphasizing his own frailty than his miraculous powers, which he regards as holding lesser importance in his identification with Christ (e.g., 2 Corinthians 12:1–14).1

Therefore, Paul’s heroic portrait in Acts is only partially explained by Paul’s own self-representation in his letters. After all, the presentation of him as an embodied vessel of divine charisma recasts Paul’s body as invulnerable to the very types of injury and pain to which he so frequently refers in his own letters, and of which he so miraculously relieves others in Acts.

In this respect, the Book of Acts represents an ambitious attempt at constructing a literary monument of apostolic memorialization, whereby Paul is recast as a courageous hero who prevails against hostile forces in the face of life-threatening dangers in his efforts to develop a vast transregional network of local Christ assemblies. Paul bravely pushes forward against threats of mob violence, arrest, imprisonment, drowning, and even a snake bite, surviving unscathed, demonstrating his corporeal invincibility and unwavering resolve. Moreover, Acts effectively solidifies Paul’s heroic legacy by pairing these exceptional accomplishments with a remarkable range of supernatural feats that put on public display Paul’s supremacy as a divine conduit in locally channeling extraordinary supernatural powers toward the benefit of others. Miraculous performances function as dramatic spectacles in staging Paul’s heroic rescues before a viewing public that marvels over the performances in wonder and amazement. These miraculous deeds garner loyalty to Christ who sits at the center of the expanding web that Paul is spinning to incorporate an ever-widening number of human beneficiaries.

Clip Art

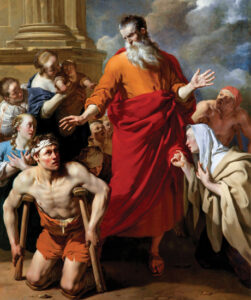

Do you recognize this famous biblical scene?

1. The Final Judgment by Jan van Eyck

2. Saul and the Witch of Endor by Benjamin West

3. The Resurrection of Christ by Jacopo Tintoretto

4. Elijah and the Angel by Godfrey Kneller

5. The Vision of the Prophet Ezekiel by Quentin Matsys

Answer: (2) Saul and the Witch of Endor by Benjamin West

In this 1777 painting, Benjamin West takes up the story of Saul and his consultation with the medium in Endor (1 Samuel 28). In the biblical account, Saul is preparing for war with the Philistines and seeks out a woman in Endor who can consult with the dead. To Saul’s surprise, she raises the shade of the prophet Samuel, who delivers to Saul a message he does not wish to hear: His kingdom is doomed. The eldritch encounter shakes Saul to his core; later, when he rides into battle, Samuel’s foretelling proves true: Saul and his son Jonathan die in the battle.

Benjamin West (1738–1820) was an American-born painter who specialized in historical scenes. He was entirely self-taught; after several years of painting mostly portraits in Pennsylvania, he visited Italy and then settled in London in 1763. His patrons there commissioned a variety of historical works, the genre for which he is chiefly known. Later in life, he took on religious themes as well, as this painting attests. Here, Saul prostrates himself before the shade of Samuel as Saul’s servants stand to his right, alarmed. The medium is on the left, conjuring the spirit of the deceased prophet.

What Is It?

1. Babylonian earring

2. Hittite door knocker

3. Roman coffin fixture

4. Parthian cymbal

5. Assyrian keyring

Answer: (3) Roman coffin fixture

This first- or second-century CE bronze disk was discovered during a salvage excavation at the site of Khirbet Ibreika, northeast of Tel Aviv. One of four lion-shaped disks uncovered at the site, the piece would have been affixed to a wooden coffin, with the small rectangular opening above the lion’s head used to hold a ring that allowed the coffin to be carried. Each disk measures around 4 inches in diameter and was handcrafted with a unique design, with each lion bearing distinctive features and a slightly different expression. Although similar lion-shaped coffin fixtures have been found elsewhere in the Levant, these are the first extant examples to have the carrying ring attached above the lion’s head rather than in its mouth.

Big City, Small Town—Why Size Matters

With rare exceptions, biblical Hebrew utilizes exactly one word, ‘ir, to reference permanent settlements—everything from tiny villages to giant metropolises. This versatility leads to its frequent use in the Hebrew Bible, where ‘ir appears some 1,093 times. Its broad range of meaning gives us multiple translation options, including “city,” “town,” and “village.” English translations usually render it as “city,” with “town” appearing much less often, and “village” used rarely or not at all. This is not best practice! As we will see, many ‘arim (plural of ‘ir) were villages, not cities or towns, and most other Israelite settlements were in fact towns, not cities.

To translate correctly, we should consider our understanding of the words “city,” “town,” and “village.”1 One factor is the number of residents: the greater the population, the more appropriate are the terms “town” and “city.” The Hebrew Bible utilizes ‘ir to reference settlements of 100,000 or more, including the ancient capitals Nineveh, Babylon, Memphis, and Thebes, which are all unquestionably cities. In comparison, Israelite settlements were not merely small, but tiny. The largest by far was eighth-century BCE Jerusalem, with a peak population of between 12,000 and 25,000. Second was probably the settlement at Tell el-Qadi, identified with biblical Dan (known as Laish in Judges 18:29), hosting 5,000 residents. No other Israelite settlement had more than 3,000 residents, and fewer than 20 had as many as 1,000.2

In addition to population, we must consider regional influence. Villages have little impact on matters beyond their gates; they exist to house and serve residents. Towns garner prominence from elements that attract visitors (e.g., administrative centers, shrines, craft makers, markets). A settlement that contains fewer residents than neighboring villages may yet be designated a town because of its regional prominence. Similarly, cities are like towns, but with greater population and influence as well as major cultural attractions, such as centers of government, learning, and religion. So to select the best English word to describe a particular Israelite settlement, we must consider population and the breadth and depth of its outside influence.

As noted above, the only ancient Israelite settlement that qualified as a city was Jerusalem, and even then, only after the construction of Solomon’s Temple in the tenth century. (Samaria, the capital of the Northern Kingdom, had significant regional influence, but its population probably never exceeded 2,000 people.) Prior to Solomon, Jerusalem was too small to be called a city. Similarly, notable settlements like Bethel (where Jacob established an altar), Hebron (David’s capital in Judah), and Lachish (a heavily fortified settlement in the Shephelah) should be referenced as towns, and sites with fewer than 1,000 residents and little influence are best identified as villages.

How does this translation strategy impact our reading of the Bible? Let’s look at occurrences of ‘ir in the Book of 1 Samuel. The first relates to Ramathaim, Samuel’s hometown and Saul’s first capital. Ramathaim is probably the unnamed ‘ir of Samuel’s residence when Saul visits him in 1 Samuel 9. Whereas 1 Samuel 7 and 8 depict the prophet as a national figure, in chapter 9, Samuel’s prominence appears more regional—in fact, Saul has never heard of him! Ramathaim may fairly be called a “village” in 1 Samuel 1, but its function as Samuel’s home base and Saul’s future headquarters suggests increased prominence that warrants the term “town.”

First Samuel also utilizes ‘ir to describe Shiloh, the home of the Ark of the Covenant and a worship center mentioned some 32 times in the Hebrew Bible, including 1 Samuel 1:3 and 4:13. Although it is important enough to host Eli and draw visitors such as Samuel’s father Elkanah, its small population (under 1,000 residents, based on the archaeological record) suggests that it was a town, not a city.

First Samuel 5:9, 11, and 12 and 6:18 refer to the five principal ‘arim of the Philistines: Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, Gath, and Gaza. In the tenth century, the Philistines, though holding a territory similar in size to ancient Judah, did not have a single capital and instead gathered around these five settlements. Excavations show that Gath and Ashkelon were substantially larger and more industrious than comparable sites in Israel, suggesting considerable influence outside their borders. Yet it is unlikely that any Philistine settlement had a population greater than 5,000, meaning these five ‘arim are best understood as “towns.”

The settlement in 1 Samuel that most merits the designation “city” is the unnamed Amalekite center in 1 Samuel 15:5. Even though archaeologists cannot guess the location envisioned by the author, Saul’s enormous army (numbering 210,000 soldiers!) makes sense only for a sizable target.

Perhaps the most important instance in which we should translate ‘ir as “village” is 1 Samuel 16:4, in which Samuel visits Bethlehem to anoint David as king. There is little archaeological evidence to suggest that Bethlehem was more than a village during David’s time. This goes hand in hand with the important idea that King David came from the most humble of beginnings, born in a place without significance (as in Micah 5:2, another verse in which ‘ir should be rendered “village”). Although it is possible Bethlehem became more prominent in later centuries owing to its strategic location (the site’s fortifications are referenced in 2 Samuel 23:14–17 and 2 Chronicles 11:5–11), it nonetheless seems to have remained a relatively small village throughout the Iron Age.

In 1 Samuel 22, Saul’s men kill all the priests of Nob, 85 men in total. Given verse 19’s description of Nob as an ‘ir of priests, the entire settlement would not have had more than several hundred residents. We do not see indications of Nob’s influence outside of its gates, so it is best understood as a village.

Finally, in 1 Samuel 27, David’s Philistine patron Achish gives him Ziklag (identified as an ‘ir) to house the families of David and his 600 fighters. The location of Ziklag is uncertain; several proposed sites indicate a preexisting settlement with a substantial history. But per the text alone, Ziklag is a village: Its primary function is to house David’s men and their families.

Unquestionably, many occurrences of ‘ir in the Hebrew Bible should be translated “city.” But we need to be careful not to overuse this option. English offers us three main words to designate permanent settlements of varying size and importance. We should use them! Surely, this will help us grasp the biblical authors’ message.

Biblical Bestiary: Dog

Favorite family pet and trusted companion, the domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris) belongs to the same taxonomic family (Canidae, “canines”) as wolves, jackals, foxes, and coyotes. It is a subspecies of the gray wolf that has evolved into hundreds of distinct breeds.

Humans kept dogs as early as the ninth millennium BCE, even before the domestication of sheep, goat, and cattle. As members of the human family, dogs have played roles as hunters, guardians, shepherds, and pets.

Highly appreciated in Egyptian society, pet dogs are frequently depicted in private tombs—active by their owners’ sides or resting under their seats. Captioned with their names in hieroglyphs, some dogs even appear on funerary stelae, where they accompany their masters for all eternity. Hunting hounds, on the other hand, were sometimes exploited for elite sport, while other dogs were intentionally killed and presented as votive mummies to the canid deities Anubis and Wepwawet.

In ancient Mesopotamia, dogs were often associated with Gula, the goddess of healing. Many dog figurines dedicated to the goddess and inscribed with prayers have been found in her shrines. Dog burials appear in cultic contexts, including an entire dog cemetery at the temple of Gula-Ninisina at Isin in modern-day Iraq. The dog’s guardian role is aptly expressed in a Sumerian proverb: “In the city of no-dog, the fox is overseer.”

Despite its positive role in herding and guarding, the dog (keleb) often has negative connotations in the Hebrew Bible, typically as a figure of insignificance. Hazael, the future king of Aram, calls himself “a mere dog” (2 Kings 8:13), and Mephibosheth says to David: “What is your servant, that you should look upon a dead dog such as I am?” (2 Samuel 9:8). In letters to a higher-status person, similar self-abasement was used in formulae of deference. Low esteem for the dog continues in the New Testament, where Jesus admonishes not to “give what is holy to dogs” (Matthew 7:6); or when Paul says about the false teachers, “Beware of the dogs, beware of the evil workers” (Philippians 3:2).

From the Greco-Roman world comes this rhyton (zoomorphic ceremonial vessel) in the shape of a hound’s head. Made in southern Italy around 330 BCE, the vessel is almost 8 inches tall. The painted scene shows a satyr walking with a plate and a fennel rod in what must have been a Dionysian revelry.

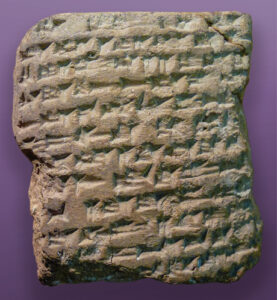

Text Treasures: Nimrud Letters: The Royal Archives of Assyria

The Nimrud Letters are cuneiform tablets from the Assyrian royal city of Kalhu (present-day Nimrud). Their contents shed light on the history of the ancient Near East in the second half of the eighth century BCE, when Assyria became a regional superpower that eventually conquered or subdued the biblical kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

The tablets received their modern name after the place of their discovery, the city of Nimrud, which sits on the east bank of the Tigris River some 20 miles southeast of Mosul in northern Iraq. In the spring of 1952, a team from the British School of Archaeology in Iraq excavated them from an ancient dump beneath the chancery offices of the so-called Northwest Palace, which was established by Ashurnasirpal II as the principal royal residence in his new capital. Despite their secondary location, the tablets likely were originally housed in the same room, since they were part of the Assyrian state archives.

The group consists of almost 300 tablets and fragments, which make up about 230 individual letters. Made of clay and shaped into rectangles to fit the human hand, they typically do not exceed 3 inches in width but vary significantly in length depending on the extent of the text. Most of the letters are written in the Neo-Assyrian dialect and cuneiform script of the Akkadian language, whereas only about 30 letters use the Neo-Babylonian dialect and script. The Nimrud Letters are currently held in the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad and the British Museum in London.

Most of these letters come from the second half of the eighth century. Although their dating and attribution is not definitive, they mostly represent the correspondence of the Assyrian kings Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 744–727) and Sargon II (r. 721–705). A small portion belongs to Shalmaneser V and Sennacherib when they were both still crown princes.

As correspondence between the Assyrian kings and their military officials and provincial governors, the Nimrud Letters provide a wealth of information on administrative and military matters of the Assyrian Empire. Among the letters’ broad range of subjects are royal building projects, tribute and taxes, international relations, and the distribution of supplies and goods. Curiously, they also elucidate the education and functions of the Assyrian crown princes and the workings of the royal express service facilitated by horses’ and mules. Significant for biblical studies, the letters offer insights into the imperial expansionist politics that led to the Assyrian annexation of Babylonia and other parts of the Near East, including the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. We also learn about deportations of populations from conquered territories—a practice illustrated in the famous Lachish reliefs from Nineveh and mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., 2 Kings 15–18; 1 Chronicles 5).

Henry W.F. Saggs, who took part in the 1952 excavations, published an edition and translation of the entire corpus in 2001: The Nimrud Letters, 1952 (Cromwell Press). A much-improved critical edition and translation appeared in 2012: Mikko Luukko, The Correspondence of Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II from Calah/Nimrud (Eisenbrauns). A searchable version is available from the State Archives of Assyria Online portal, with facsimiles and photos of the tablets also available online, from the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative.

Scholars refer to individual letters by their publication acronym (CTN V for Saggs’s edition in the Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud series; SAA 19 for Luukko’s edition in the State Archives of Assyria series) followed by a sequence number. For example, the tablet pictured opposite is CTN V 164, which corresponds to SAA 19 25. In what is the earliest mention of Ionian Greeks in Assyrian sources, Tiglath-Pileser III’s official on the Levantine coast informs the king: “The Ionians came and gave battle … They did not take anything (and) when they saw my troops they embarked their boats and fled into the midst of the sea.”

Losing Abraham’s Religion: More on Israelite Religion in Egypt

In part one of this two-part article,a we considered evidence from within the Book of Exodus that suggests that, in the view of some biblical authors, the Israelites maintained the ancestral religion of the Patriarchs during their lengthy sojourn in Egypt. In part two, we take into account further material in Exodus, as well as in later biblical and post-biblical traditions, that suggests that they abandoned it, at least in part.

The first piece of evidence to consider is the Israelites’ neglect of the practice of circumcision. According to the Pentateuch, circumcision was instituted in and practiced throughout the ancestral period (Genesis 17:10–14). It was the sign of the covenant God made with Abraham and was to be a perpetual ordinance for Abraham and his descendants. Whether or not it was practiced consistently among the Israelites during the Egyptian sojourn—or indeed at any point prior to the post-exilic period—is unknown. Early Jewish interpreters supposed that when Pharaoh’s daughter opens the basket in which Moses has been placed and exclaims that he is a Hebrew (Exodus 2:6), it must be because she observes that he is circumcised. However, some modern scholars have pointed out that since Pharaoh has decreed that all baby boys must be thrown into the Nile, she would surely conclude that any child so abandoned to the river must be Israelite. Consequently, this episode probably provides no clues about whether the Israelites were practicing circumcision during the Egyptian sojourn.

Many years later, when Moses is returning to Egypt after having lived among the Midianites for about two decades, he is traveling with his wife, Zipporah, and his son, Gershom. The text, though difficult, appears to recount that, along the way, the Lord tries to kill Gershom because he is uncircumcised (Exodus 4:24). This would seem to indicate that, as an Israelite, Moses should have already circumcised Gershom on the eighth day after his birth, in accordance with the patriarchal tradition (Genesis 17:12). Clearly, however, he had not.

A second piece of evidence that the Israelites abandoned their ancestral religion may be that they did not practice sacrifice while in Egypt. According to Exodus 5:1, Moses and Aaron petition Pharaoh to let the Hebrews go, so that they can celebrate a festival in the wilderness: “Let us go three days’ journey into the wilderness to sacrifice to the Lord our God, or he will fall upon us with pestilence or sword” (Exodus 5:3). Sekel Tob, a 12th-century midrash, interpolates a Mosaic explanation that “from the time our ancestors left Canaan we have not offered him a single sacrifice.” The implication is that the Israelites could suffer greatly for their neglect of sacrificial worship.

A third clue may be that the Israelites did not know the divine name Yahweh. In part one, I suggested that the ancestors had known the name Yahweh; yet, when God appears to Moses in the burning bush and announces that he is going to send him to liberate the Israelites, Moses asks how he should answer if they ask him the name of the god who sent him (Exodus 3:13). If, as I suggested in the previous installment, the ancestors had known the divine name, why would Moses need to ask it here? Although there are several interpretive possibilities, one suggestion is that, if they had known the divine name in Egypt, they must have forgotten it.

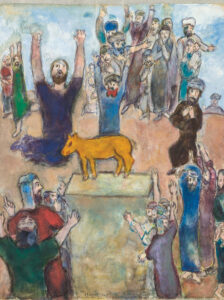

A fourth clue is the golden calf episode. In Exodus 32, when Moses comes down from the mountain with the two tablets of the covenant, he finds the Israelites worshiping an image of a calf. One longstanding view is that the calf was meant to represent Yahweh. But the fact that Moses burns the calf with fire, grinds it into powder, scatters it on the water, and makes the people drink it (Exodus 32:19–20) suggests otherwise. There were numerous bull, cow, and calf divinities in ancient Egypt, and the golden calf probably represented one or more of these.1 That the Israelites would so quickly return to the worship of one of these deities suggests that they had become familiar and comfortable with them during their time in Egypt.

A fifth indication is that of later biblical traditions in which the period of Egyptian bondage was characterized by idolatry. The Book of Joshua claims that, after the people had moved into the Promised Land, Joshua led the Israelites in a covenant renewal service in which he challenged the people to “put away the gods that your ancestors served beyond the River and in Egypt and serve the Lord” (24:14). Apparently, during the period of Egyptian bondage, some Israelites worshiped the gods of Mesopotamia, while others had adopted the worship of the gods of Egypt.

Many years later, in the sixth century BCE, the prophet Ezekiel recounted that, when Yahweh had chosen Israel and swore to them that he would bring them out of Egypt, he urged them to cast away the gods of Egypt, but “not one of them cast away the detestable things on which their eyes feasted, nor did they forsake the idols of Egypt” (Ezekiel 20:8).

In this brief review of biblical traditions related to the questions about Israelite religious practice during the time between the conclusion of the ancestral period and the inauguration of Mosaic religion, we have seen that the evidence is mixed. There are some clues that suggest the biblical writers understood that at least some Israelites maintained the ancestral religion, but there are others that indicate that the Israelites as a whole did not. If this was indeed the case, it only served to highlight for the (later) Israelites their special connection to God as demonstrated in the Exodus and thereafter. As the psalmist declares, yes, their ancestors strayed in Egypt, “yet he saved them for his name’s sake” (Psalm 106:8).

A Thousand Words: Joshua’s Conquest

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, a little-known literary and artistic tradition reached its peak in Persia: the production and illustration of Judeo-Persian manuscripts. Texts generally fall into two categories: Hebrew transliterations of great Persian literary works, on the one hand; and original Judeo-Persian poetic compositions, on the other. The language used in these works is a dialect of Persian heavily influenced by Hebrew and Aramaic and written using the Hebrew alphabet.

The manuscript shown here, dating to the late 17th or early 18th century, is a copy of the Fath Nama (“Book of Conquest”), originally written around 1474 by the Jewish-Persian poet Imrani of Isfahan. The text is a poetic paraphrase in Judeo-Persian that aims to render on an epic scale the great biblical narratives in Joshua, Ruth, and Samuel.

A key component of the Judeo-Persian manuscript tradition is the use of miniature illustrations to accompany the text, such as those that appear in this manuscript. Miniature art of this type flourished under the Safavid dynasty (16th–17th centuries) and gained wide-spread use in subsequent periods. This image depicts Joshua and the people of Israel preparing to cross the Jordan River with the Ark of the Covenant. They are dressed in late 18th-century Persian garb. Joshua is in the center at the top, presiding over the crossing; his head is ringed with a stylized halo. Below and to the left, the ark is being carried over the water.