What’s in a Name?: Tiglath-Pileser

Tukultī-apil-Ešarra

Tukult.ī = “my trust” | apil = “heir of” | Ešarra = “Esharra temple”

Tukultī-apil-Ešarra is an Akkadian royal name attested in written sources from ancient Assyria and neighboring regions, including Israel and Judah. Its modern spelling, Tiglath-Pileser, is adopted from the Hebrew Bible (2 Kings 15:29), where it appears also as Tilgath-Pilneser (2 Chronicles 28:20).

The name is a nominal sentence, meaning that its predicate is not a verb but a noun, with the verb “to be” implied but not expressly written. In this case, “trust” (tukultu) is the subject, with a first-person possessive suffix (-ī): tukultī, “my trust.” The predicate is the noun aplu, “heir,” further identified as related to Esharra. The relationship (“of,” in English) between aplu and Ešarra is expressed through a construct form (aplu to apil), hence apil Ešarra, “the heir of Esharra.” This gives the phrase “My trust is the heir of Esharra.” But what does this mean?

Esharra was an ancient temple in Ashur, the religious capital of the Assyrian Empire, dedicated to the homonymous Assyrian chief deity, the warrior god Ashur. Assyrians understood the Esharra temple to be ritually connected to an even earlier Sumerian temple to the god Enlil in Nippur. And because Enlil’s son was the warrior god Ninurta, later Assyrian kings associated him with their own god Ashur. On the surface, the phrase “the heir of Esharra” then refers to Ninurta, but the ideological reference is to Ashur. Thus, between these layers of meaning, the name Tiglath-Pileser really means, “My trust is (the god) Ashur.”

Of the three Assyrian kings who bore this name, Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 744–727 BCE) was the most consequential. A central founder of the Assyrian Empire, he transformed Assyria into a superpower that, under subsequent rulers, conquered Babylon and eventually subdued most of the Levant, including the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. In 2 Kings 15:19, Tiglath-Pileser III is called Pul, which reflects his Babylonian name, Pūlu.

Ancient Courts and the Letter of James

The New Testament’s Letter of James has received much less attention than the letters of Paul. Questions linger about the short letter, such as who actually wrote it, when, where, and why. Although there is some consensus about certain aspects of the book, such as its urban background or the author’s indebtedness to Hellenistic Judaism, much of the work continues to garner debate among scholars.

One such debate centers on James 2:1–7, where the author describes two figures: a gold-ringed man dressed in “shining clothes” who enters the assembly, and another fellow in dirty clothes. James states that the well-appareled man receives good treatment from the audience and is graciously offered a seat, while the poorly dressed one is ordered to stand or sit at their feet. For James, such actions manifest preference or partiality for the finely clothed individual, while they dishonor the second man (2:6).

Some interpreters think this scenario, which would be a common enough occurrence in the honor- and status-conscious world of Mediterranean antiquity, reflects a meal setting, while others argue that a worship meeting is presupposed. I contend, however, that the author has in mind a courtroom scene, based on clues in the text itself.1

First, it is worth remembering that courts in the Roman Empire were usually public. This means that legal disputes were on full display to the city’s population. A typical day out for an urbanite might include watching a trial for some time, depending upon how interesting and entertaining it was. A great range of people could therefore observe and become familiar with the various procedures and behaviors that took place in the context of legal disputes. There is no reason to think that someone deeply embedded in Hellenistic Judaism, as the author of James was, would not have watched the drama of a court case unfold before his eyes. And it is clear that those who identified with Judaism, including those who became Christ-followers such as the author of James, were active in metropolitan contexts throughout the Roman Empire.

Although today we might not think of courtroom dynamics as particularly entertaining, they could be in antiquity, because the participants would dress and behave in certain ways to impress or earn the sympathy of the judges or jurors. A well-clad person was advertising their power and status. A person in dirty clothes, such as the figure in James, may have deliberately donned such attire because wearing besmirched clothing was a means of advertising that they had been wronged in some way.

We know of other ancient examples of this practice, such as one described by Seneca the Elder (Declamations 10.1.2), where a young man dresses in soiled clothes and follows around after a rich man who allegedly murdered the youth’s father. The young man has been sued by the wealthy person for libel, and his dirty clothes reflect his defendant status. Similarly, Quintilian also counsels litigants to wear mourning clothes, which usually consisted of garments rubbed in ashes or dirt, as a means of garnering support for one’s cause at court (Institutes of Oratory 6.1.33). Of course, it is possible that dirty clothes might simply point to a person’s indigence, but it is clear that such garb, which could be worn by a wealthy person, could also communicate that an injustice had occurred. James 2:2 indicates clearly that the second man is in dirty clothing, which could therefore signal that he has been wronged in some way.

In Roman courts, benches for judges, jurors, defendants and their supporters, as well as for the audience, could be moved around. Often, the space between the person accused and the judges or jurors was not great, such that defendants could fall at the feet of magistrates and beg for mercy if necessary. One wonders, then, if James’s description of the audience’s poor treatment of the man in soiled dress, ordering him to stand or sit at their feet (2:3), reflects knowledge of the physical features of these courts. Such an order suggests that the audience has made a distinction between the well and poorly dressed men, and thus that they have become judges with evil thoughts (2:5). Taken in by the apparent power and influence of the gold-ringed man in shining clothes, they apparently command the other individual to supplicate at their feet even before he has had a chance to make his case. James condemns such outrageous behavior. Such corruption was commonplace in Roman courts, where preferential treatment of wealthy and high-status people was widespread. In fact, displays of partiality were the norm, not the exception, in ancient courts. In my view, James reflects an awareness of these pervasive injustices.

Some might object to a courtroom scenario on the basis that James refers to a “synagogue” as the place that the two men enter (2:2). However, a variety of activities took place in ancient synagogues, including legal proceedings, and there are indications that Roman and later rabbinic legal proceedings shared things in common. It could be that James has in mind a legal dispute that did not take place within an official court setting, but occurred among members of the audience, in the synagogue. Paul, for example, recommended that the Corinthian church try to resolve their disputes internally (1 Corinthians 6:1–8). But even if James is imagining a legal setting within the group to which he writes, its features, including the dress of the litigants and the physical characteristics of the courtroom (ancient synagogues usually had benches against the walls), could be modeled on the court scenes that he witnessed within the matrix of ancient public life more broadly.

This short discussion may address a minor issue among the many that puzzle interpreters of James. In antiquity, however, to show unjust favoritism within an ancient court, whatever the context, could have devastating consequences, including exile or death for litigants. If a courtroom is the setting for the scenario that James describes in 2:1–7, then it illustrates to what extent acts of partiality were not only a violation of the Torah, but also potentially deadly within such a world.

The Fall of Jerusalem: Who Was to Blame?

In ancient literary accounts detailing the falls of great cities, the question of where to assign blame typically emerges. Different authors offered different reasons why the gods would allow their city to be conquered. A brief review of this millennia-long historiographic tradition—from ancient Mesopotamia to Homeric Greece—highlights the unique approach of the biblical authors in explaining the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 586 BCE. Indeed, as we’ll see, the version of Jerusalem’s fall preserved in the Hebrew Bible was likely one of several competing narratives available to its original audience to explain the destruction.1

One Bronze Age tradition about a city’s demise comes from a text known as the Song of Release, which tells of the destruction of Ebla, a Syrian city that had achieved international influence already in the third millennium BCE. Found at Hattusa, the Hittite capital, and dating to around 1400 BCE, the poorly preserved epic includes one key scene describing a conversation between King Meki of Ebla and his council of elders. Meki conveys the storm god’s demand that they release captives from a certain town called Ikinkalis; the god promises victory and prosperity if they do and utter destruction if they do not (compare Deuteronomy 28). One elder rejects Meki’s argument, and the council sides with him (contrast Rehoboam in 1 Kings 12:1–20). This leaves Meki to attempt to expunge his city’s sin by pleading his case before the god’s statue—but to no avail.

This version of the “fall of a city” story absolves the king of all blame and puts it squarely on the backs of the city’s elders, which suggests the song was meant to flatter royal interests. Strikingly, it runs counter to the common Near Eastern storyline, in which it is the cultic failings of the city’s ruler that are to blame for the suffering inflicted on his subjects.

Accordingly, the Sumerian Curse of Agade (c. 2100 BCE) blames the Sargonic king Naram-Sin for the fall of his dynasty (2340–2160 BCE) and its capital city Agade (also known as Akkad) by asserting that he tore down the temple of Enlil. Interestingly, however, the Akkadian Cuthean Legend of Naram-Sin (c. 1800 BCE) responds to the earlier account by presenting the king as well-meaning but understandably resistant to his diviners’ claim that the gods have decided to destroy Agade. Clearly, we should expect that different sets of survivors of fallen cities offered competing storylines when making sense of their trauma.

Elsewhere in the Mediterranean world, the story about the fall of Troy found in Homer’s Iliad (eighth century BCE) incorporates the plot types attached to both Ebla and Agade. One key episode mentioned in the Greek epic parallels the assembly scene of the Song of Release. Apparently, before the main events of the Iliad, the Trojan council of elders refused the demand of the Achaean ambassadors to return Helen because they had been bribed by her seducer Paris (3.204; 11.22–24). Meanwhile, the general plotline of the Cuthean Legend of Naram-Sin is assigned in the Iliad to Hector, who willfully rejects the advice of his augur and refuses to retreat within the city walls, setting up his fatal confrontation with Achilles (12.200–243; 18.253–312; 22.98–107).

In combining different versions of Troy’s fall, the Iliad distributes blame between its council and various members of the royal house. Meanwhile, it suppresses two more versions of the fall of Troy that follow more closely the standard Near Eastern pattern by blaming Troy’s first king Laomedon—either because he rudely sent away Apollo and Poseidon after they had built Troy’s walls (Iliad 7.442–63; 21.436–60; marginal note to Iliad 21.444), or because he reneged on his promise to recompense Heracles for slaying a pernicious sea monster (Iliad 14.249–62; 15.12–35; Pindar, Nemean Ode 4.25–30; Isthmean Ode 6.27–35).

When it comes to the fall of Jerusalem, the biblical authors writing stories of the city’s destruction in the post-exilic period were extremely concerned about assigning blame. By assiduously denying that the kings of Judah (i.e., David’s dynastic line) were responsible and blaming instead the stiff-necked people of Israel (just as the Song of Release blames the city council and absolves Meki), the Bible resists the traditional reasoning of Mediterranean historiography and argues for continued support of the Davidic line.

Still, the biblical scribes included juicy details about the dynasty’s failings, from David’s betrayal of Uriah (2 Samuel 11–12), to Solomon’s catering to the idols of his many wives (1 Kings 11), to Rehoboam’s harsh rule. Apparently, these were too well known to the scribes’ original post-exilic audience simply to be overlooked. Therefore, we can infer that the version preserved for us, which explains how God remains faithful in his commitment to the all-too-human line of David (2 Samuel 7), was originally arguing against a rival version of events in which the failings of the Davidic rulers are to blame, transgressing against God and their own people.

When the exiles returned from Babylon to Jerusalem around 538 BCE, they encountered people now living in the vicinity who opposed the intentions of the newly returned to reinstall priestly families and rebuild the Temple (Ezra 4; Nehemiah 1:2–3). It would have been those people left behind who adhered to the standard storyline blaming the king for the fall of his city, while the returners would have followed a party line congenial to the Davidic court exiled in Babylon. This is the viewpoint—placing blame on the people of Israel—that is articulated by Nehemiah when he prays to God to support his return to Judah in order to manage the restoration of Jerusalem (Nehemiah 1:4–11). No surprise, then, that Isaiah’s and Ezekiel’s excoriations of the people of Israel are what made it into the post-exilic version of events available to us in the Hebrew Bible, and that Lamentations does not dare transfer blame to the Davidic line, even as the mourning voice of Jerusalem passionately describes the brutality of God’s punishment.

Whence-A-Word?: Writing on the Wall

The common phrase “writing on the wall” comes from the biblical story of Daniel and the Babylonian king Belshazzar (Daniel 5) in which a mysterious inscription predicts the king’s impending doom.

In the Book of Daniel, the Babylonian king Belshazzar throws a party for some 1,000 of his noble guests at which he decides to drink from cups that his predecessor, Nebuchadnezzar, had taken from the Jerusalem Temple. Suddenly, a mysterious hand appears, writing on the plaster wall an inscription that nobody seems able to decipher. Then comes Daniel (also called Belteshazzar), who during his exile in Babylon was made the chief of the Babylonian magicians, having explained previously the dream of King Nebuchadnezzar about a tree (Daniel 4). He reads the writing on the wall as mene, mene, teqel, uparsin, translating it as “numbered, numbered, weighed, and divided.”

Paradoxically, the Book of Daniel is one of only two biblical books written mostly in Aramaic. Sixth-century Babylonians would have been able to understand the language, so it is confusing that King Belshazzar and his wise men cannot read the sentence. It could be due to some kind of cryptography, or perhaps they simply do not understand what they are reading. Nevertheless, Daniel interprets the supernatural inscription as a divine judgment against Belshazzar, explaining that God has “numbered” the king’s days, that the king has been “weighed” and found wanting, and that his kingdom has been “divided” and given to the Medes and Persians. Although modern scholars continue to wrestle with the sentence’s grammar, Daniel’s interpretation uses the double meaning of each word’s root letters: mnh meaning both “to count” and “to finish”; tql meaning “to weigh” and “to be wanting”; and prs meaning “to divide” and “Persia.”

In modern usage, the inscription on the plaster wall in Belshazzar’s palace at Babylon signifies something apparently ominous. Sometimes referred to with the shorthand expression menetekel, the phrase “writing on the wall” is synonymous with a clear warning sign heralding someone’s doom or an inevitable catastrophe.

Biblical Bestiary: Locust

Locusts are a type of grasshopper that can swarm. Since there is no taxonomic difference between grasshoppers and locusts, they are impossible to distinguish in artistic representations. Of approximately 12,000 grasshopper species, which all belong to the family Acrididae, only 19 can swarm and are considered locusts. Two species have lived in the lands of the Bible: the desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) and the migratory locust (Locusta migratoria).

Although grasshoppers are solitary winged insects inhabiting grasslands and semi-arid regions of all continents except Antarctica, locusts persist in hot and dry areas, including the Sahara Desert. When conditions are right, locusts change color and transition into the migratory gregarious phase; they then form groups and eventually take to the skies. Riding the winds and consuming their own weight in food every day, locusts can travel great distances devastating crops and pastureland. During such outbreaks, swarms consisting of billions of ravenous insects can cover hundreds of square miles. To this day, locust plagues cause famines and trigger human migrations.

Unsurprisingly, the Hebrew Bible, which uses ten different words to signify the insect or its different stages, portrays locusts as terrible pests (2 Chronicles 7:13; Psalm 105:34–35; Joel 1–2), most famously in the Egyptian plagues narrative (Exodus 10:3–19). In Judges 6:5 and Jeremiah 46:23, enemy armies are compared to swarms of locusts, a common literary theme across the ancient Near East. Although the Torah prohibits eating most insects, it permits eating certain types of grasshoppers and locusts (Leviticus 11:22). Indeed, grasshoppers are highly nutritious and have been consumed in different cultures for millennia. In the Gospels, John the Baptist is reported to have lived on “locusts and wild honey” during his wilderness ministry (Matthew 3:4; Mark 1:6).

Among the rare artistic representations of grasshoppers is this small amulet, now in a private collection. Less then 2 inches long, it is made of lapis lazuli and likely comes from Roman-era Egypt. Other ancient illustrations come from Egyptian wall paintings as well as Assyrian reliefs showing servants bringing locusts to a royal feast.

Women and Prophecy in Biblical Israel

Attempts to define the biblical prophets often start with the etymology most scholars accept for the Hebrew word for “prophet”: nabi (a male prophet) and nebi’a (a female prophet) are both passive participles of the Hebrew root nb’, “to call.” A prophet, then, is “one who is called” or, by inference, “one who is called by God,” more specifically, “one who is called by God to deliver God’s message.” Sometimes, these prophets deliver God’s message through dramatic acts: In Jeremiah 19, for example, God commands the prophet to break a pottery vessel into pieces in order to symbolize that God intends to “break” the people of Jerusalem—which is to say, God intends to unleash divine wrath upon the people as punishment for the evil things they have done in God’s eyes. More typically, though, prophets deliver God’s word orally, often by proclaiming, “Thus said Yahweh,” and then giving voice to God’s pronouncements.

The Bible’s women prophets can conform to this definition. An excellent example is Hulda. According to her story, recounted in 2 Kings 22, she is a prophet living in Jerusalem in the 18th year of the reign of King Josiah of Judah (622 BCE).a At the king’s command, his secretary, Shaphan, along with several others, seeks her out to “inquire of Yahweh” regarding the credibility of the book of the law that had recently been found in the Jerusalem Temple (2 Kings 22:8). Hulda responds by speaking in the name of Yahweh concerning the book, which most scholars typically identify as some version of the Book of Deuteronomy, reporting that its statutes do indeed reflect God’s will and that Judah, having failed to live up to them, will be punished for its transgressions.

Deborah, identified as a prophet in Judges 4, also performs the prophetic function of receiving messages from the deity and then communicating those messages on God’s behalf. Thus, according to Judges 4:6, Deborah summons a man named Barak and delivers to him God’s command: He is to raise an army and do battle against the Canaanite general Sisera. Deborah further decrees the outcome of the battle: “I [Deborah speaks here for God] will give him [Sisera] into your [Barak’s] hand” (Judges 4:7). There are hiccups, however, as Barak refuses to act according to the deity’s command unless Deborah accompanies him to the battlefield. Deborah agrees but warns that Barak’s reticence will redound negatively upon him: “I will surely go with you,” she tells him, “but glory will not come to you via the path you are following, for Yahweh will sell Sisera into the hand of a woman” (Judges 4:9). And so it comes to pass: Deborah goes to the battlefield with Barak, and Sisera’s army is defeated by the Israelite troops, but Sisera himself is killed by a woman named Jael after he flees from the fighting and takes refuge in her tent. b

Another woman prophet, Miriam, is similarly understood as able to fulfill the prophetic role of conveying messages on God’s behalf. In Numbers 12:2, she, along with her brother Aaron, challenges the seemingly sole authority of Moses, God’s ultimate representative (and their other sibling), by asking (rhetorically), “Has he [God] not also spoken through us?”c However, in the biblical text in which Miriam is specifically identified as a prophet (Exodus 15:20–21), the words to which she gives voice are not an oracle she delivers on God’s behalf but a hymn she sings in praise of the deity after the Israelites’ miraculous escape at the Reed (traditionally, “Red”) Sea. Deborah, too, is remembered for singing the hymn found in Judges 5, lauding God for leading the Israelites to victory over Sisera. Our definition of the Bible’s women prophets, therefore, may need to expand to include the roles they had as musicians.

We may also need to expand our definition to include these women’s work as medico-magical authorities who specialize in providing care to Israelite women. In an enigmatic text found in Ezekiel 13:17–23, Ezekiel condemns a cadre of “daughters of your people who prophesy” for, among other things, their use of wrist bands and some kind of head drapes. According to many, these “daughters” are necromancers, who tie snares of some sort to their arms to capture dead spirits.1 However, some other scholars propose that the “daughters who prophesy” sew bands of cloth onto other women’s wrists and put head drapes on other women’s heads as medico-magical acts. Similar traditions are known from Mesopotamia, whereby bands and knotted strings were tied around the heads, necks, torsos, and limbs of childbearing women to address difficulties they were facing during their pregnancies.2

Overall, there is no simple definition that can capture the many roles the Bible’s women prophets seemingly assume. Rather, like women today, ancient Israel’s women prophets were the ultimate multitaskers, undertaking a variety of activities on God’s behalf.

Clip Art

Do you recognize this portion of a painting of a famous biblical story?

1. Noli me tangere by Fra Angelico

2. The Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck

3. The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch

4. The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise by Giovanni di Paolo

5. The Archangel Michael by Dosso Dossi

Answer: (2) The Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck

This oil-on-panel painting, completed between 1436 and 1438, depicts the final judgment of Jesus Christ at the end of time. At the top is Jesus himself, flanked by angels and seated at the head of a great council of saints, apostles, virgins, clergy, and nobility. This scene represents heaven. Just below, the archangel in the center of the image calls forth the dead from land and sea. Below is a grim hellscape into which are cast those not admitted into heaven.

The work is paired with another of Van Eyck’s paintings depicting the Crucifixion (not shown). Together, the two panels form a diptych, that is, a single work consisting of two parts; however, modern research has revealed that they originally served as the two side panels of a triptych or the doors of a tabernacle or reliquary shrine.

Like its counterpart, The Last Judgment measures less than 2 feet in height, showcasing Van Eyck’s extraordinary skill at achieving exquisite detail on a miniature scale. In addition to the Hebrew, Greek, and Latin inscriptions within the painting itself, the wood frame also bears inscriptions of biblical texts in both Latin and Middle Dutch.

Define Intervention

What is a “pesher”?

1. A type of grinding tool

2. A biblical song or hymn

3. A type of biblical commentary

4. Part of a camel’s harness

5. An ancient list of tribes or cities

Answer: (3) A type of biblical commentary

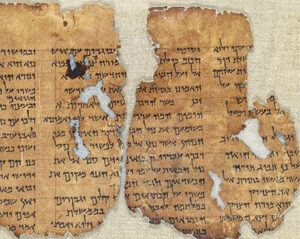

A pesher (plural: pesharim) is a distinctive style of biblical commentary known most famously from the Dead Sea Scrolls. It is essentially a line-by-line walkthrough of a biblical text, with each line or section followed by an interpretation—a pesher—that purports to illuminate or explain the biblical passage.

A number of pesharim are attested among the Dead Sea Scrolls, but the most famous is known as Pesher Habakkuk (the first columns of which are pictured here). This scroll was one of the initial seven to be discovered, and it continues to shape scholarship on the scrolls and the Qumran community. A sample from this document provides a clear example of the pesher style, with the text of the Book of Habakkuk interspersed with comments every few lines:

“Dread and fearsome are they; their justice and dignity proceed from themselves.” (Habakkuk 1:7)

Its pesher (interpretation) concerns the Kittim (Romans), the fear and dread of whom are on all the nations; all their thoughts are premeditated to do evil, and with cunning and treachery they behave toward all the peoples.

Most notable in this example, as throughout the Qumran pesharim, is the inclination to read the biblical text as bearing directly on the time and circumstances of the pesher’s authorship. Thus here, whereas in the biblical context the verse from Habakkuk is part of a lengthy pronouncement about the Babylonians, the author of the pesher reads it instead as a reference to the Romans—the empire in control of the southern Levant when the commentary was written.

The Table of Nations: A Geographic Odyssey

According to the Book of Genesis, after the great flood receded, Noah’s three sons disembarked from the ark, and “from them the whole world branched out” (9:19). Genesis 10 then provides a detailed account of where Noah’s descendants settled. It presents a genealogical list of names known as the Table of Nations, with each name representing a different group of people.1 For instance, Javan signifies the Ionians or Greek groups in the northwest, Madai indicates the Medes in the northeast, and Hazarmaveth represents the people of Hadramaut, located in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula, among many others spanning a vast geographic expanse.

In recent years, scholars have pondered how the biblical writers, who represented an inland population and who typically focused on internal Israelite affairs, gained access to such extensive geographical knowledge. They have proposed various sources of inspiration or information. One potentially fruitful avenue is to examine Mesopotamian literature, considering the Table of Nations’ association with the Flood narrative (which originated in Mesopotamia) and the broader influence of Mesopotamian culture on Israelite literary models. Mesopotamian literature features several instances of geographical and encyclopedic texts, such as the Babylonian Map of the World and works detailing the extent of Sargon II’s empire, such as the Sargon Geography.2 Both texts demonstrate substantial geographical knowledge and literary prowess. However, scholars acknowledge that Mesopotamian geographical compositions differ from the biblical Table of Nations in terms of content, genre, and extent of geographical focus. Unlike the Table of Nations, which primarily serves as a genealogical lineage listing the eponymous descendants of the protagonist of the Flood story, these Mesopotamian works primarily emphasize geographical details. Thus, while the two bodies of literature may share common elements, the biblical Table of Nations stands apart in its distinct focus and purpose.

Furthermore, although the biblical Flood story has its origins in Mesopotamia, none of its Mesopotamian precursors depicts the protagonist or his sons as the fathers of the world’s nations, nor do they emphasize the genealogies of these eponymous fathers. Figures such as Ziusudra, the Sumerian flood hero, and Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh attain eternal life but are subsequently removed from the human sphere, with their descendants left unmentioned.

Many years ago, Umberto Cassuto briefly proposed an alternative way of understanding the origins of the Table of Nations. He noticed the similarities between it and the lamentation for Tyre in Ezekiel 27, both of which demonstrate a comprehensive knowledge of geography.3 In this lamentation, Ezekiel vividly portrays Tyre as a grand and opulent ship, constructed from the finest materials sourced from various regions across the ancient world (Ezekiel 27:3–7). Nations from far and wide participated in the operation of this ship: “The inhabitants of Sidon and Arvad were your rowers … The elders of Byblos and its artisans were within you … Paras and Lud and Put were in your army,” and so forth (27:8–10). Drawing a parallel between Ezekiel’s prophecy concerning Tyre and the Table of Nations in Genesis 10, Cassuto proposed that both lists of peoples might be rooted in geographical traditions acquired by Phoenician traders and settlers through their extensive connections with surrounding lands.

Unfortunately, only a few literary works have survived from the ancient Phoenician world that might strengthen Cassuto’s hypothesis, largely due to the prevalent practice in the Levant of writing on perishable materials. Nonetheless, there is some late fragmentary evidence suggesting that Phoenician literary traditions did include lists of eponymous names. The use of geographical or ethnic names in genealogies in the style of Genesis 10 can be found, for example, in the second-century CE writings of Philo of Byblos (as preserved by Eusebius), who apparently drew upon earlier Phoenician traditions; for example, he offers a description of an old generation of peoples bearing the names of mountains or mountain ranges, including Casius (Mt. Zaphon), Lebanon, and Anti-Lebanon (Eusebius, Preparation for the Gospel 1.9–10). The next generation saw the birth of two brothers whose parentage is not specified: Samemroumos, also called High-in-Heaven (Hypsouranios), who founded Tyre, and his brother Ousoos who quarreled with him. The first brother represents šmm rmm, a district within the ancient city of Tyre, while the second represents Ushu, the name of mainland Tyre.

Further support for Cassuto’s hypothesis may come from early Greek genealogical compositions first put in writing in the late seventh or early sixth century BCE. Recent editions of Hesiod’s Catalogue of Women, a seminal Greek genealogical work,4 along with new studies of Greek mythographers in prose, offer a comprehensive approach to early Greek genealogical material and its parallels with the Pentateuch.5 Notably, similarities between Greek genealogical compositions and Genesis include the depiction of ethnic groups descending from a flood hero. Just as Noah begets Shem, Ham, and Japheth in the biblical narrative, the Greek flood hero Deucalion—son of Prometheus and grandson of the Titan Iapetus—holds a central role in Greek genealogical traditions. Deucalion begets Hellen, the forefather of the Greeks, whose three offspring become the progenitors of major Greek groups: Dorus, Aeolus, and Xuthus, the father of the Ionians and the Acheans (Hesiod, preserved in Plutarch, Table Talk 9.747f).

The parallels between biblical sources and Greek genealogical traditions are significant, particularly considering the absence of the dispersion of peoples following the flood in Mesopotamian accounts. While a direct link between biblical and Greek sources cannot be claimed, it is noteworthy that the Greek flood account is believed to have originated from the ancient Near East rather than being indigenous to Greece. The flood protagonist holds a prominent place in Greek genealogical traditions, although the flood story itself did not attain the same prominence in Greece as it did in the ancient Near East. Scholars suggest that the flood story reached the Greek world through contact with civilizations in the northern Levant or Syria during the Archaic period (c. eighth–fifth centuries BCE). It is plausible that this Syro-Levantine flood narrative included the genealogical pattern of placing the flood protagonist at the head of genealogical lists, along with other unique motifs.

If the Greek flood story indeed reflects Syro-Levantine traditions, then this may further support the claim that the biblical Table of Nations is based on geographical, mythological, and genealogical traditions that circulated in the eastern Mediterranean. Writers from this region described their history and delineated their ethnic identity in comparison to neighboring groups by drawing upon the Mesopotamian legacy and reworking these traditions and old notions in a new spirit. Thus, the genealogical-geographical lists in Genesis 10 are but examples of similar traditions prevalent in the eastern Mediterranean. Although the Mesopotamian geographical texts cannot serve as a close model to the biblical Table of Nations, the lament to Tyre in Ezekiel 27 and several Greek genealogical works preserve similar broad geographical traditions and may attest to interconnections and interrelations between civilizations of the pre-Hellenistic eastern Mediterranean.

How Many?

How many chapters of the Biblical Archaeology Society were formed around the United States?

Answer: At least 14 chapters

In 1981, the Biblical Archaeology Society (BAS) launched its chapter program with the goal of connecting like-minded individuals who shared a passion for biblical archaeology. BAR founder Hershel Shanks gathered a group of friends and acquaintances from around the country who shared his vision and brought them all to Washington, D.C., for a planning meeting. It was decided that BAS’s home office in Washington would serve as the national headquarters, supporting the chapters by advertising their groups and programming in BAR and by providing one speaker a year. From this initial meeting, the chapters grew to at least 14 groups from Los Angeles to New York and everywhere in between.

In addition to hosting regular meetings in which top scholars and well-known BAR authors were invited to give lectures on their work, chapters also organized short courses on biblical archaeology, toured local museums, and represented BAS at conventions.

Although most of the local chapters eventually closed or disbanded, a few continue to exist in various forms, either as email or social media groups or as wholly independent organizations with their own lectures and events, most notably the Biblical Archaeology Society of Northern Virginia.