Strata

016

Virtual Temple Mount

Computerized Exhibit Opens at Foot of Ancient Site

Visitors to Jerusalem can now take a virtual tour of the Temple Mount as it appeared during the Herodian period (first centuries B.C. and A.D.), and they can do it in the shadow of the real Temple Mount. But the Ethan and Miriam Davidson Exhibition and Virtual Reconstruction Center was criticized by some Palestinians immediately after its opening on April 17, who claimed the center seeks to write them out of Jerusalem’s history.

The Virtual Reconstruction Center is located in the early-Islamic-period (seventh and eighth centuries A.D.) Umayyad Palace complex at the entrance to the Jerusalem Archaeological Park near the Old City’s Dung Gate. It contains a small museum area with artifacts found in the excavations conducted near the Temple Mount by Benjamin Mazar, Ronny Reich and others; a brief video showing a modern visitor and his ancient counterpart (played by the same actor), who has brought his goat offering to the priests at the Temple; a computer simulation of the Temple Mount built by Herod the Great before it was destroyed by the Romans in 70 A.D.; and two computer workstations where visitors can surf an interactive research Web site on Jerusalem’s history. But you don’t have to be in Jerusalem to search the site; simply go to www.archpark.org.il.

For many visitors, the highlight is the computer simulation, which allows viewers to observe a trumpeter signal the arrival of the Sabbath, view the exquisite decorated domed ceilings within the Hulda Gate or look down the length of the Royal Stoa along the southern end of the Temple Mount. Viewers can also examine photos of the artifacts on which the virtual reconstruction is based. The computer reconstruction employs the same high-definition digital video technology used on flight simulators by the U.S. Navy, combined with the latest sound technology used on Web sites of such pop stars as Madonna.

“This is not the movie Gladiator. It is all based on archaeological evidence,” said Jacob Fisch, director of external affairs and traveling exhibitions for the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA). He notes that after emerging from the center, visitors find themselves only 50 yards from the actual Herodian Temple Mount.

The Davidson Center lies buried within the 25-foot-high chambers of a palace originally used by the Umayyad rulers (661–750 A.D.). Only an unobtrusive glass entryway protrudes above the center’s roof.

Two years in the making, the center was a combined effort of the IAA, led by longtime Jerusalem excavator (and BAR contributor) Ronny Reich; a team of Israeli architects; and Lisa Snyder, a computer expert from the Urban Simulation Team of the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at UCLA.

“When building a computer model, there is the problem of how to present the Temple based on the differing information we have,” Reich said. “We had to decide how to represent each particular spot; we couldn’t just leave white spaces. It’s a traumatic job for a scholar to decide between several thousand possible versions.”

The IAA is considering the creation of similar exhibits on other areas, eras and cultures from Jerusalem’s history. Next on the list is a virtual tour of Umayyad sites in Jerusalem. However, this has not placated Kamal Rian, a leader of the Islamic Movement in Israel and an opponent of the Davidson Center. He denies the Jewish Temple ever existed on the Temple Mount, insisting it was located elsewhere. Following the center’s opening, Rian warned on Israeli television that the exhibition would trigger riots worse than those that occurred after the 1996 opening of the Temple Mount Tunnel alongside the Mount’s Western Wall. His prediction proved wrong.

The IAA offered free admission to the center for the first two months. But with the continuing violence in Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the offer was taken up mostly by Israelis—tourism is at a near-record low since the outbreak of the second Palestinian intifada (uprising) last fall.

017

Victory on the Harbor

Greek Remains Found at Dor

For 15 years, archaeologist Andrew Stewart has been hoping to find more evidence of life during the Hellenistic period at Dor, the ancient port city along Israel’s northern coast, where he directs the University of California at Berkeley team digging with Ephraim Stern of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The team has uncovered rich remains from the Canaanite, Israelite, Phoenician and Persian erasa (c. 1200–330 B.C.), although Stewart, a professor of art history and classics, has uncovered frustratingly few Hellenistic remains. But this past season he had his Victory.

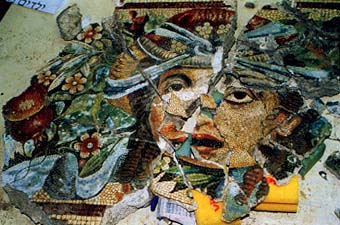

Last August, Stewart’s team discovered a 2,200-year-old headless statue of the Greek goddess Victory (more commonly known by her Greek name, Nike). The statue was found along with fragments of a Greek temple and remains of the temple’s columns in a late-second-century B.C. pit that had been filled with debris when the temple was destroyed. Stewart speculates that the destruction occurred during the invasions by Antiochus VII Sidetes (a Seleucid king) and Simon Maccabee in 139/8 B.C. or by the Jewish king Alexander Jannaeus in 100 B.C. In another pit, barely 50 feet away from the first and probably filled in the during a first century A.D. Roman campaign of urban renewal, the excavators discovered a floor mosaic—probably from a villa dining room. It depicts a theater-mask consisting of a young man wearing a fantastic party hat decorated with fruit and flowers. Such masks were used in the performances of Greek comedies. The mosaic, says Stewart, is unique in the Hellenistic east and “is easily the equal of the famous mosaics from Delos, the palaces at Pergamon and the House of the Faun at Pompeii, which it most closely resembles. It puts Hellenistic Israel squarely on the map in the sophisticated art of fine mosaics, hitherto known at this time only from Alexandria.”

The mosaic, like the temple, probably dates to the second century B.C. Both finds seem to predate by at least 100 years any other monumental evidence of the Greeks in this part of the Levant.

Dor, a city known from the Bible, was originally settled by the Canaanites, then ruled by a group of the Sea Peoples. In the tenth century B.C. King Solomon made it his harbor city; in 732 B.C. it was captured by the Assyrians and served as the capital of the coastal province of Duru.

Although Greeks were known to have settled in Dor and even to have controlled the city at times. it has never been clear how large their settlement was. The new discoveries point to a substantial community.

“These finds add a new chapter to Greek art and architecture,” Stewart says. “As far as I’m aware, no one had found Greek architecture, sculpture and mosaics like these in Israel before.”

018

Cyrus H. Gordon, 1908–2001

Maverick Scholar Mastered Many Fields

Cyrus H. Gordon, a giant in Biblical and ancient Near Eastern studies, died on March 30, 2001, at the age of 92, at his home in Brookline, Massachusetts. With his passing, the world of scholarship has lost not only a brilliant intellectual, but also the last link to a distant past. I refer not to antiquity, but rather to the 1920s and 1930s, when academic nephilim (giants) walked the earth and when major discoveries were revolutionizing Biblical studies.b

Gordon became involved in the field at a very young age: He published his first article at 21, and first visited the Near East at 23. Because of this early start, Gordon knew many of the luminaries of the 20th century, including the archaeologists Sir Flinders Petrie and Sir Leonard Woolley. Gordon was recently describing his early fieldwork to a young archaeologist when the young man said with amazement, “You worked with Woolley at Ur and you’re still alive?”

Between 1931 and 1935, Gordon lived in Iraq, in small villages among Arabs, Kurds, Yezidis, Mandeans, and Aramaic-speaking Jews and Christians. But he also dug with William F. Albright at Tell Beit Mirsim, and accompanied Nelson Glueck on his exploration of Transjordan. Gordon constantly peppered his classes and his publications with firsthand observations of the Near East gained during those years.

Gordon loved to talk about his life. His autobiography, A Scholar’s Odyssey, was published last year by the Society of Biblical Literature and won a National Jewish Book award.

Born in Philadelphia on June 29, 1908, Gordon soon showed a strong proclivity for languages; during his teens he mastered not only Hebrew but also Aramaic, Latin and German. Gordon received his B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Pennsylvania.

Scholars consider Gordon’s most important contribution to be his books on Ugaritic, beginning with his Ugaritic Grammar (1940) and culminating with his Ugaritic Textbook (1965). Generations of Biblical scholars learned Ugaritic through Gordon’s books.

Gordon himself, however, considered his most significant accomplishment to be his decipherment of Minoan. Sir Arthur Evans had discovered two sets of inscriptions on Crete, now called Linear A and Linear B. The latter is the earliest form of Greek that we know; Gordon believed Linear A to be Semitic, though he failed to convince many of his colleagues.

Gordon taught at Dropsie College, in Philadelphia, at Brandeis University and at New York University, from which he retired in 1989 at age 81. During 44 years of teaching, Gordon produced more than 90 doctoral students, of which I am proud to count myself as one. But it is not just the number of his students that is remarkable, it is the range of their specialties: Most focused on Bible, Ugaritic and Akkadian, but he also supervised dissertations on Hittite, Hurrian, Egyptian, Coptic, Aramaic, Syriac, Mandaic, Greek and archaeological subjects.

Cyrus Gordon’s life was complete. He died at home surrounded by his loving wife, Connie, and his five children. At the funeral, David Neiman, a former student, said it best: “Cyrus had enough achievements in one lifetime for three or four lifetimes.”

Prize Established in Memory of Sean Dever

The W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem has announced a $500 award to be given annually for the best paper or article by a Ph.D. candidate. The award is named after Sean Dever, son of Norma and William Dever. Sean’s father has been a frequent contributor to BAR and is a former director of the Albright Institute. Sean Dever died in April at age 32 from an aneurysm after having overcome cancer twice. Papers or articles, as well as contributions to the prize fund, can be sent in care of Sam Cardillo, Treasurer, Albright Institute, P.O. Box 40151, Philadelphia, PA 19106.

017

What Is It?

A. Coffin

B. Dog house

C. Scroll repository

D. Oven

018

What It Is, Is …

A. Coffin.

This clay ossuary, or box for the bones of the dead, measures 26 by 20 inches and served as the final resting place for an individual who had died during the Chalcolithic era (4500–3200 B.C.) at Azor, 5 miles southeast of modern Tel Aviv. The flesh of the deceased was first allowed to decay, and the bones were then placed in an ossuary for final burial. Ossuaries were fashioned in various shapes; this one resembles a house of the Chalcolithic era and was meant to serve as a new home for the deceased in the afterlife. Ossuaries became popular among the well-to-do in Jerusalem during the era of King Herod (first centuries A.D. and B.C.). These were carved from limestone and bore elegant decorations and, in some cases, the name of the person whose remains were contained within.

Virtual Temple Mount

Computerized Exhibit Opens at Foot of Ancient Site

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

See Avraham Negev, “Understanding the Nabateans,” BAR 14:06.

See Robert S. MacLennan, “In Search of the Jewish Diaspora,” BAR 22:02.