Ein Gedi Synagogue Records Missing or Lost

Calling all cars! Calling all cars! Has anyone at Hebrew University in Jerusalem seen the records from the excavation of the ancient synagogue at Ein Gedi?

It was excavated almost 35 years ago by archaeologist Dan Barag, who never wrote a final report of his excavation (or even a preliminary report). The only published record of the dig is a popular article in Hebrew—in the Israeli journal Qadmoniot. Barag was recently considering applying for a Shelby White-Leon Levy grant to finance the research required to finally publish the scientific results of the excavation. When he tried to locate the records at Hebrew University, where he teaches, however, they were nowhere to be found.

Ein Gedi is a lovely site on the western shore of Dead Sea. The results of the excavation of the synagogue proved extraordinarily rich: a clearly preserved outline of two buildings on top of one another, one with two phases; a Torah shrine; a hoard of coins from the Byzantine period; a bronze menorah; a water basin for congregants to wash their hands and feet (the only such installation ever found in a synagogue); and a charred wooden disk from the bottom or top of a pole around which a Torah was once rolled.

But the most eye-popping finds of the excavation were three mosaic pavements. One, in the western aisle of the prayer hall, consists of four extensive Hebrew and Aramaic inscriptions—quotations from the Bible, commemorations of donors to the synagogue building, curses on those who would divide the community or pass on malicious tales to the gentiles and a literary zodiac (that is, a verbal description of the heavens).

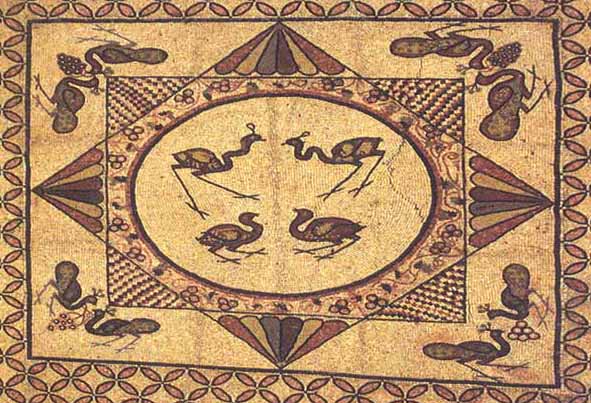

The main prayer hall featured a lovely mosaic consisting of two nested rectangles, a diamond and a circle, enclosing two pairs of birds. The corners of the outer rectangle are decorated with pairs of peacocks and bunches of grapes. The spaces are filled with unusual geometric designs.

When this mosaic floor was lifted, another mosaic floor was found lying beneath it. In contrast to the unusually colorful upper mosaic, this lower mosaic was simple white and black. The mosaic itself was also simple: a rectangle inside of which was—a swastika! What it was doing in this synagogue from about 1,700 years ago we can only speculate. Swastikas appear not infrequently in numerous ancient cultures. Was it simply decorative? Or did it have some other meaning?

Notice that the date is uncertain—about 1,700 years ago. The date of the earliest synagogue—with the swastika mosaic—has never been definitively studied. That would be done in the final report, which would also include numerous other matters that professional archaeologists study. But, alas, that will never be done in the case of the Ein Gedi synagogue—unless someone answers our calling-all-cars.

Linder and Maher Named in Other Honors

Avraham Biran, still an active archaeologist at age 92, was awarded the Israel Prize, that nation’s most prestigious civilian honor, in April. Previous archaeologists to win the prize constitute a Who’s Who of Israeli archaeology: Yigael Yadin (1956), Shmuel Yeivin and Benjamin Mazar (1968), Nahman Avigad (1977), Ruth Amiran (1982), Claire Epstein (1995) and Trude Dothan (1998).

Biran’s long career began during the British Mandate period in Palestine, when he served as a district officer in the Galilee and in Jerusalem. After the establishment of the State of Israel, he held various government positions, including, most notably, director of the Department of Antiquities and Museums (today the Israel Antiquities Authority). In 1966 Biran began excavations at Tel Dan, near the Lebanese border, which has become Israel’s longest-running dig. At Dan, his team uncovered an inscribed slab containing the phrase Beit David, “House of David,” the first reference outside the Bible to ancient Israel’s king. In 1974 Biran became director of the Nelson Glueck School of Archaeology at Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem; he plans to retire from that position this year.

Also honored recently was Elisha Linder, who received the Percia Schimmel Award from the Israel Museum. Linder specializes in maritime archaeology; he founded the Underseas Exploration Society of Israel and helped establish the Center for Maritime Studies at the University of Haifa. He has excavated at most of the major marine sites in Israel and has also explored sites in Sardinia, Sicily and Italy. We published his article “Excavating an Ancient Merchantman,” BAR 18:06.

Edward F. Maher, of the University of Illinois at Chicago, is the first recipient of the Sean W. Dever Memorial Prize. The honor is named for the late son of Norma and William G. Dever, professor of archaeology at the University of Arizona, and is granted annually by the W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem for the best paper by a pre-doctoral student. Maher’s winning submission was “Food for the Gods: The Identification of Sacrificial Faunal Assemblages in the Ancient Near East.” Sean Dever died last year at age 32 of an aneurysm after having overcome cancer twice.

Masada and Acre Join Old City of Jerusalem

UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, has designated Masada and Acre (also called Akko) as World Heritage Sites. UNESCO seeks to preserve historic sites so that “future generations can inherit the treasures of the past.” Other locations to have earned the designation include the Old City of Jerusalem (the only site in Israel previously on the list); the historic centers of Prague, Vienna, Dubrovnik, Venice, Florence and Paris; the great cathedrals and castles of France and Germany; the Vatican and Forum in Rome; as well as the Acropolis in Athens, the Taj Mahal, the Pyramids, Petra, the Great Wall of China, Stonehenge, the Statue of Liberty and the Grand Canyon.

Masada, near the southwestern shore of the Dead Sea, was built by Herod the Great as a desert palace and refuge but is most famous as the last stronghold of Jewish rebels against Rome following the fall of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. It is the second-most visited site in Israel, after Jerusalem; the readers of Condé Nast Traveler magazine recently voted Masada as “World’s Best Monument.”

UNESCO cited Acre, a walled port city just north of Haifa, for its historic townscape, particularly its Islamic urban design. In addition to its splendid Islamic remains, Acre also boasts important Crusader remains, many of them underground.

“Intelligent Design” Proponents Want Their Theory in Public Schools

Some readers of the Bible still have trouble with certain widely held scientific theories. Our sister publication, Bible Review, has reported on the removal, and subsequent return, of the theory of evolution from the list of required topics in the Kansas public school science curriculum. And when our article on the ramp at Masada (“It’s a Natural: Masada Ramp Was Not a Roman Engineering Miracle,” BAR 27:05) referred to the geologic formations near the Dead Sea as millions of years old, we braced ourselves for some flak; sure enough, we got it (see “Millions of Years Off the Mark,” Queries & Comments, BAR 28:01).

Now there’s a new wrinkle in the culture wars: the debate over the Intelligent Design theory, which claims that life is so complex that some sort of rational designer must be behind it. Unlike creationists, the proponents of intelligent design accept that the earth is billions of years old and that organisms evolve over time, but they argue that natural selection, a cornerstone of Darwin’s evolution theory, is not the only factor involved.

Two of the theory’s champions appeared before the Ohio Board of Education in March to urge that it be taught in the state’s schools as an alternative to Darwinian evolution.

According to the New York Times, Stephen C. Meyer, a professor of philosophy at Whitworth College in Spokane, Washington, and a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute, a Seattle organization that propounds alternative scientific theories, told the board that scientists frequently make “design inferences,” for example that the hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone were deliberately carved and did not result from random erosion. Intelligent design proponents argue that the same inference can be legitimately applied to natural diversity.

Jonathan Wells, a colleague of Meyer’s at the Discovery Institute and a biologist and religious studies scholar, denied accusations that the intelligent design movement was an attempt, veiled in scientific garb, to force religious viewpoints into the public schools. “I’m not trying to tell you who’s right and who’s wrong here,” Wells said. “Is the design that we all see real or merely an appearance?”

Two scientists appeared before the board to counter Meyer and Wells. Lawrence Krauss, chairman of the physics department at Case Western Reserve University, in Cleveland, said that while many questions remained unanswered by natural selection, decades of experimentation and discovery had strengthened Darwin’s theory. “The real danger is in trying to put God in the gaps,” Krauss told the board.

Kenneth R. Miller, a biologist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, told the board that there was little support for the intelligent design viewpoint among mainstream scientists and said that the theory was “propped up from outside the scientific community” to pressure legislators and school officials.

Krauss added that the school board’s format of having two speakers who supported the intelligent design theory and two who opposed it was misleading. He estimated that scientists opposed the idea 10,000 to 1. Meyer countered that public opinion polls show that 71 percent of the public support teaching the intelligent design theory.

A. Musical instrument

B. Dollhouse

C. Planter

D. Animal trap

What It Is, Is …

D. Animal trap

When the peoples of the fertile crescent began to give up their nomadic lifestyles for settled agriculture about 10,000 years ago, communities began to construct large silos in which to store grain. With the storage of grain comes the problem of rodents—the remains of ancient granaries contain numerous rodent skeletons—forcing agriculturalists to devise ingenious ways of keeping vermin under control.

This terra-cotta trap was made in about 1200 B.C. and comes from Tell Meskene in present-day Syria. Its size—15 inches by 5 inches—suggests it was used to catch rats: attracted by bait, an unlucky rodent that entered through the open (right) end would have tripped a mechanism that closed a door behind it.

This object is one of nearly 400 Syrian artifacts currently on display at the Fernbank Natural History Museum in Atlanta, Georgia, as part of the traveling exhibition, Ancient Empires, Syria: Land of Civilizations. The exhibition runs until September 2; for more information call 404–929-6300 or visit www.fernbank.edu.