Bible Books

004

Jesus and the Spiral of Violence: Popular Resistance in Roman Palestine

Richard A. Horsley

(San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987) 355 pp., $27.95

Occasionally there appears a volume that rearranges the historical landscape. Richard Horsley’s work does just that with its fresh reconstruction of Roman Palestine and the ministry of Jesus.

The author counters the traditional view that a sect of Zealots came to dominate first-century Israel and drew the nation into war with Rome (66–70 A.D.). According to Horsley, “zeal” was a minor factor, and the group calling itself “Zealots” did not form until 68 A.D. Without the Zealot hypothesis, a complex picture emerges, which Horsley paints with the aid of socio-historical studies of violence, terrorism and revolution. He sees an agrarian society with a wealthy elite and impoverished peasants; a tense “colonial situation” in which imperial Rome dominated politically, economically and culturally through the Jewish rulers; and a breakdown of village life leading to widespread popular resistance.

Horsley analyzes the history of the period in terms of stages in the spiral of violence: 1) institutional exploitation by the rulers; 2) popular protests; 3) severe repression by the establishment; and 4) revolution. He elucidates the diverse forms of popular resistance to Roman domination. These forms included protests by intellectual groups such as the Fourth Philosophy, the offshoot Pharisaism founded by Judas the Galilean, which advocated “No lord but God”; popular mass demonstrations under Archelaus, the Emperor Gaius and several procurators; and “apocalyptic” movements expressing hope for an historical transformation—the main religious motivation of the rebellion. These popular protests brought on repression, which in turn led to revolution.

Horsley portrays Jesus in light of these socio-historical realities, rejecting the picture of Jesus “sketched with the Zealot movement as a foil” (p. 149). In Horsley’s view, Jesus was similar to the prophetic movements of Judas the Galilean and Theudas. His apocalyptic outlook was historically oriented, and he addressed the economic and political situation. He was not a pacifist in some abstract, individualistic sense, but “actively opposed violence,” particularly institutional oppression, in nonviolent ways (p. 326). The charges against Jesus—that he claimed to be a king, stirred up the people and opposed tribute to Rome—“were not totally false” (p. 160).

The focus of Horsley’s analysis is that Jesus’ proclamation of the Kingdom of God called concretely for a social revolution in the villages. Jesus’ renewal included healing, forgiveness and exorcism. Jesus did not recruit groups of tax collectors, prostitutes or the poor to form a following apart from Galilean society. Rather, he sought social renewal within village life by calling for egalitarian familial relations, nonhierarchical communities, the cancelling of debts, the love of enemies (cooperation at a local level), nondefensive sharing, mutual assistance, and reconciliation. Such a renewal required repentance, trust without anxiety, and humility.

At the same time, Horsley argues, Jesus spoke and acted against the corrupt Jewish hierarchy that contributed to the breakdown in village life. In fact, he condemned the Temple system itself, for soon the Temple would be destroyed and the vineyard given to others, making way for a popular king-ship unmediated by either a “hierocracy or a temple system” (p. 325). Jesus’ prophetic social revolution was preparation for the kingdom of God—an imminent political revolution in history by which God would break the spiral of violence, end the established order, liberate Israel with justice and bring salvation to the nations.

My disagreements with Horsley’s analysis are vastly overshadowed by appreciation for his fresh analysis of first-century Israel and for the bold, new strokes with which he portrays the historical Jesus. His contributions make this work an even stronger offering than his Bandits, Prophets, and Messiahs (with John Hanson [Minneapolis, MN: Winston-Seabury, 1985]), which was a co-winner of the 1986 BAS Publication Award for the “best scholarly book relating to the New Testament and early Christianity.” This latest volume should be read along with Marcus Borg’s Politics, Holiness, and Conflict in the Teaching of Jesus (New York: Edwin Mellen, 1984). These two works move in the same orbit, yet each deals with what the other neglects. Together they renew our interest in the historical Jesus in exciting and timely ways.

In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History

John Van Seters

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983) 399 pp., $36.00

“History” has long been an important category in biblical interpretation, since so much of the Bible is devoted to the recounting of past events in which the 005activity of God was perceived. Some interpreters have gone so far as to say that the biblical faiths, Judaism and Christianity, take history more seriously than do any other religions. In the pages of the Hebrew Bible, according to numerous scholars, we have the first real history writing in the ancient world. Chief among the candidates as the first real history are several blocks of material that are usually dated around 950 B.C., in a period of “enlightenment” during the reign of Solomon: the Story of David’s Rise (1 Samuel 16-2 Samuel 5), the Court History of David (2 Samuel 9–20, 1 Kings 1–2), and the sections of the Pentateuch ascribed to the “Yahwist” writer.a

John Van Seters agrees that Israel was the first nation in the ancient Near East to produce history writing. But he does not mean what has commonly been meant by that claim. He does not mean that Israel was the first culture to think “historically” about the past. Nor does he mean that Israel was the first culture to think of its God as active in historical events. Van Seters takes as his starting point a definition formulated by the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga: “History is the intellectual form in which a civilization renders account to itself of its past.” Van Seters argues that the Israelites were the first to integrate a broad variety of materials into a complex, unified narrative that communicated to the nation a sense of its identity. He does not, however, believe that this kind of writing appeared in Israel until about 550 B.C.

Across the ancient Near East there were historiographical genres such as king lists, chronicles, annals and royal inscriptions, which recorded and interpreted the past, and the first half of Van Seters’s book gives a most useful survey of this material. But by itself, historical consciousness was not enough to produce history writing. According to Van Seters, history writing emerged only when someone took the further step of composing from the assorted historiographical genres an orderly story of the past which gave the nation a sense of who they were. This happened first in Israel in the sixth century and in Greece in the fifth century. Van Seters pleads for biblical scholars to give more consideration to a comparison of Israelite and Greek historiographical techniques. He himself devotes much attention to Herodotus, who took an assortment of disparate materials and genres and composed a unified narrative for the Greeks. Van Seters does not press too hard the case for direct continuity between the Greek culture and the Israelite (although he does speculate briefly about some contact via Phoenicia). His goal is the somewhat more modest one of convincing biblical scholars, as they hypothesize about how the narratives in the Hebrew Bible took shape, to consider the techniques Herodotus used to compose a unified narrative as well as the model, more commonly used by biblical scholars, of a communal process of evolving traditions.

In Van Seters’s estimate, the first historian in Israel was the anonymous figure—the “Deuteronomistic Historian”—who composed the narrative now found in the books of Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings. The evidence that this block of material is a unified composition was persuasively presented by the German scholar Martin Noth in 1943. Noth demonstrated that a chronological framework ties the whole body of material together and that a theology derived from the Book of Deuteronomy pervades the corpus—thus the label “Deuteronomistic History.” This Deuteronomistic theology is expressed in stock phraseology at a number of points in the biblical narrative: Israel, as the elect people of Yahweh, is obligated to Yahweh and to the laws of the covenant established at Mt. Horeb (Sinai); Israel’s obedience to these laws will lead to peace and prosperity, whereas disobedience will bring punishment Noth held that the Deuteronomistic History, found in Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings—as well as in a new introduction and conclusion to the Book of Deuteronomy (chapters 1–4, 31–34)—was composed about 550 B.C. The purpose of the Deuteronomistic History was to demonstrate to the Israelites that their apostasy was responsible for the downfall of their nation. Noth believed that the Deuteronomist, the author of the History, made considerable use of older, pre-formed sources, such as the Story of David’s Rise and the Court History of David; in these sections the Deuteronomist contributed mainly editorial touches.

Van Seters affirms Noth’s basic thesis, but he believes that the Deuteronomist deserves more credit for originality than Noth gave him. Van Seters is persuaded that it is very difficult to identify earlier sources behind the final text, and he is quite critical of efforts to reconstruct hypothetical stages in the development of the material prior to the final text, an approach scholars call “tradition criticism.”

It is, in fact, his belief that the Deuteronomist originated much of the content of his own work, just as Herodotus seems to have done (according to at least one school of interpretation). For example, in Van Seters’s judgment, the Deuteronomist created the stories of Joshua’s conquest as a narrative expression of the Deuteronomic theme that Israel should remain pure and should obliterate everything un-Israelite. For the period of the Judges, Van Seters thinks that the Deuteronomist perhaps knew some assorted hero-stories, out of which he constructed the present narrative. In 1 Samuel 1–7 (the childhood of Samuel and the Ark’s capture by the Philistines), he observes, it is “scarcely possible … to recover earlier stages in the tradition… if they ever existed.” Regarding the account of Solomon’s reign, Van Seters says: “The whole presentation is a rather elaborate reconstruction by the Deuteronomist based upon very little prior material.” The theme of divine election and rejection of kings throughout the monarchical period Van Seters labels a “literary artifice” of the Deuteronomist. Such stories as the establishment of golden calves in Dan and Bethel by Jeroboam I (1 Kings 12:26–30) and the discovery of the book of law in the Temple during Josiah’s reign (2 Kings 22:3–20) he regards as pure fiction.

It is in his treatment of the Court History of David, however, that Van Seters departs most sharply from recent scholarship. The Court History is frequently cited as a high-water mark in Israelite historiography, dating from the time of Solomon, and one of the Deuteronomist’s primary sources. But Van Seters argues that the Court History’s portrayal of David as “a moral and spiritual weakling” is so out of accord with the Deuteronomist’s portrait of an ideal David that he could hardly have incorporated the Court History into his work. Far from being a product of the tenth century B.C., the Court History is a post-Deuteronomistic addition to the Deuteronomistic History, a product of the post-Exilic period in the sixth century. Consequently, the Court History is no contender for the title of Israel’s first history writing, according to Van Seters.

As a sustained challenge to much conventional thinking about the composition of the Hebrew Bible, this book deserves serious attention. At a time when other scholars have also expressed misgivings about our ability to reconstruct the stages of composition of the Bible prior to the canonical text and are seeking a better understanding of the compositional techniques that led to the 007final text, Van Seter’s work is a particularly stimulating and helpful contribution to biblical scholarship.

In a work of this scope, almost every scholar will disagree with certain points. Let me identify some of the problems that I find here. Van Seters argues that the Yahwist’s narrative (the earliest of the Pentateuchal strands, dated by most scholars to the tenth century B.C.) was in fact composed while the Israelites were in exile in Babylonia in the sixth century B.C., and after the Deuteronomistic History. A fundamental theme in the Yahwist’s narrative is the promise to the patriarchs that Yahweh would give them numerous progeny, who would possess the land of Canaan. Van Seters holds that this theme was invented in the Exilic period to encourage the Israelite exiles to trust in Yahweh to increase their numbers and to restore them to the land of the promise. I have difficulty believing that such a freshly contrived notion, without any pre-Exilic basis, could have had the power to inspire the exiles. Moreover, if none of the Pentateuchal narratives were in existence when the Deuteronomistic History was written, why would the Deuteronomist write a history of Israel without narrating in full the monumental Exodus events and the patriarchal story alluded to in Deuteronomy 26:5–9 and other texts? The most reasonable assumption is that the story of those events had already been written. Indeed, certain texts in the Deuteronomistic material seem to presuppose the existence of the Pentateuchal narratives (e.g., Deuteronomy 1:8, 10, 34–39, 34:4; 1 Samuel 12:6–8).

Van Seters refers to the Deuteronomist’s concept of an “ideal David,” Which he finds at odds with the image of David in the Court History. Van Seters apparently has in mind the frequent references in the Deuteronomistic History to the effect that such and such a king compares favorably or unfavorably with “my servant David, who kept my commandments and followed me with all his heart.” But I would note that whenever this David standard is mentioned, the commandments referred to have to do with cultic matters (cf. 1 Kings 9:4–9, 11:4–8, 14:8–9; 2 Kings 16:2–4). It is with regard to cultic obedience that it may be said of David that “he wholly followed Yahweh.” It is quite conceivable, therefore, that the Deuteronomist did not consider David’s adultery with Bathsheba and his sending of her husband, Uriah, to his death in battle as contradictions to David’s fulfillment of the standard of wholehearted righteousness in cultic matters. Although Van Seters presents additional reasons for taking the Court History as a post-Exilic supplement to the Deuteronomistic History, a major link in his argument is removed if one concedes that the portraits of David in the two works are not incompatible. Van Seters does not cite evidence within the Court History that inherently requires a post-Exilic date.

Van Seters makes very little reference to the thesis, held by a growing number of scholars, that the sixth century B.C. Exilic edition of the Deuteronomistic History was preceded by an edition prepared during the reign of Josiah (640–609 B.C.). Since the events recorded in 2 Kings 25 of the Deuteronomistic History carry the story down to about 560 B.C., the final edition obviously originated after that date.

However, a number of features in the Deuteronomistic History seem to point to an earlier version originating before the fall of Judah in 587 B.C. For example, after the theological commentary in 2 Kings 17:7–23 on the fall of the northern kingdom, we would expect a similar peroration on the fall of Jerusalem, but none occurs. Also, Josiah seems to be presented as a ruler like David and the ideal king prophesied by Moses in Deuteronomy 17:18–20 and therefore as the culmination of the Deuteronomistic narrative. Moreover, the existence of a Josianic edition of the Deuteronomistic History would bolster Van Seters’s argument that “the notion of the Davidic promise of a perpetual dynasty [2 Samuel 7] is a basic ideological construction that is no older than the Deuteronomistic History”; it is difficult to imagine a theologian devising this hopeful ideology at the time of the Exile, when historical events would seem to undercut it severely. The theory that there were two editions of the Deuteronomistic History is held by a respectable group of scholars. It would be helpful to have some discussion of this theory by Van Seters, especially since its acceptance would require some reshaping of his own thesis.

The Apocryphal Old Testament

Edited by H. F. D. Sparks

(Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1985) 1,012 pp., $44.50

The Apocryphal Old Testament has endured a longer gestation than most books. It had its inception in the 1950s and was intended to be a less costly, more convenient collection of pseudepigraphic texts than the rather dated second volume of R. H. Charles’s The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha 009of the Old Testament. The criterion used in choosing ancient texts for this new anthology was “whether or not any particular item is attributed to (or is primarily concerned with the history or activities of) an Old Testament character (or characters).” Twenty-five books were selected, ten of which had appeared in Charles’s second volume. The table of contents indicates that the translations of six of these ten are revisions of the renderings that were published in Charles’s collection. An introduction and bibliography contributed by Sparks precede each of the translations.

Because the work was so long in the making, new discoveries, new editions of texts and changing tastes in translation style made Sparks’s editorial work devilishly difficult. He explains that he tried to modernize the English of the translations to make them conform to the style of Michael Knibb’s rendering of 1 Enoch, which is reprinted in the book. He writes: “I can only hope that the result will not be judged too aggressively modern.” There is little danger of this, since one meets a generous sprinkling of words and phrases such as “behold,” “and it came to pass,” etc. At times the result is a curious mixture of older and more recent language (see, for example, Jubilees 22:7: “I give thee thanks … because thou hast let me see this day; behold, I am …an old man with a long life-span”). It should be said, though, that despite many weaknesses of these kinds, the translations read fairly smoothly for renderings of ancient texts.

In general, the book offers a valuable collection of texts. It is always possible to quibble about why one work was included and another excluded, but it does seem strange that 2 Esdras (= 4 Ezra) was not included. Sparks explains that it was omitted because it “belongs, strictly speaking, to the Apocrypha.” That this should be a reason for exclusion may well come as a surprise, given the title of the book. It serves, however, to highlight how bizarre it is to entitle the volume The Apocryphal Old Testament when the book contains, not the Apocrypha, but what everyone today calls the “Pseudepigrapha.” The editor’s attempt to justify this decision makes as little sense as the decision itself.

Eschatology in Old Testament

Donald D. Gowan

(Philadelphia: Fortress, 1986) 159 pp., $9.95

In Eschatology in the Old Testament, Donald E. Gowan offers the reader a study of Israel’s traditions regarding eschatological matters, rather than an analysis of what the individual authors of Old Testament books teach about the subject. Although he focuses on themes and deals with the canonical shape of the books, his approach is historical in that he traces traditions from their earlier, non-eschatological appearances to their reuse in eschatological contexts in the Old Testament. He also follows them briefly in their subsequent roles in post-Old 010Testament Jewish and Christian literature. For him the term eschatology entails a radical break with the status quo; thus, his book centers upon “those promises that speak of a future with significant discontinuities from the present.”

Gowan states that two “discoveries” led him to organize the book as he does. The first was realizing that, according to the programmatic passage Ezekiel 36:22–38, three transformations must occur for God to right all wrongs: transformations of the person, of society and of nature. These three topics provide the subjects for chapters 2–4. The other discovery was that “Jerusalem appears with a prominence unparalleled by any other theme” in eschatological contexts. Consequently, chapter 1 is entitled “Zion— The Center of Old Testament Eschatology.” Gowan adds to these four chapters a conclusion named “Old Testament Eschatology and Contemporary Hope for the Future.” Here he affirms that the Old Testament’s worldly hope of a social eschatology firmly under divine control has strong implications for contemporary ethics. The practical nature of his conclusion echoes a similar concern throughout the body of the book, where he adds to each major section a unit called “Contemporary Manifestations.”

Gowan should be commended for writing a rather comprehensive, yet brief, study of an important aspect of Old Testament thought. He has assembled a large collection of data and analyzes it in a clear fashion. With its combination of historical, theological and contemporary concerns, the book should appeal to a wide audience. Although one may well ask questions about issues such as the actual role of Zion in biblical pictures of the future, Gowan’s book fills a need as a very useful introduction to the eschatology of the Old Testament.

Paul—His Letters and His Theology

Stanley B. Marrow

(Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1986) 278 pp., $9.95 paperback

The Pauline Circle

F. F. Bruce

Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1985) 106 pp., $4.95 paperback

The Pauline Letters

Leander E. Keck and Victor Paul Furnish

(Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1984), 156 pp., $9.50

Books on Paul the Apostle speed off the presses at the rate of some 40 per year. Those reviewed here provide a rich sampling of the Pauline fare publishers are serving these days.

Readers who would like to update their understanding of Paul might profitably commence with Stanley Marrow’s book, Paul—His Letters and His Theology. Marrow gives his readers a lively, timely and popular introduction to Paul’s life, letters and theological themes. In presenting Paul’s life and theology, Marrow relies more on Paul’s genuine letters than on the Acts of the Apostles. He is of the opinion, as are Leander Keck and Victor Furnish and many other contemporary commentators, that there are only seven genuine Pauline letters: Romans; 1 and 2 Corinthians,

This is an excellent introduction to Paul. The author writes clearly and has a keen interest in applying Paul’s themes to contemporary Church life. Readers should be aware that the volume contains no explicit treatment of the other New Testament letters that bear Paul’s name: 2 Thessalonians, Colossians, Ephesians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy and Titus. Readers should also be aware that in stressing theological themes, this book does not deal extensively with the social background of Paul and his congregations, for instance, what it meant for the well-to-do Roman citizen Paul to engage in the lowly job of “tentmaker” and what it meant for poor Christians at Corinth to meet in the house of a rich Christian for the Lord’s Supper.

Paul has often been portrayed as a solitary figure, the “rugged individual” type of missionary, who stormed through the cities of Asia Minor and Europe, and had even made plans to evangelize the peoples at the western boundaries of the Roman empire. F.F. Bruce tries to correct this portrait by presenting popular biographical sketches of the people who formed Paul’s inner circle, his “school,” or, as a Catholic friend of mine puts it, his “traveling chancery office.” In Paul’s circle there is Ananias, Barnabas, Silas, Timothy, Luke, Priscilla and Aquila (the first missionary couple), Apollos, Titus, Onesimus and Mark—to say nothing of Paul’s “co-workers” and his “hosts and hostesses.”

Bruce is surely right in accentuating the importance of Paul’s “team” in the formulation of his theology and in the conduct of his mission. And he is also correct in adding his voice to those of many contemporary scholars who emphatically note that many of Paul’s “co-workers” were women. He writes of Euodia and Syntyche, mentioned in Philippians 4:2: “Whatever form these two women’s collaboration with Paul in his gospel ministry may have taken, it was not confined to making tea for him and his circle—or whatever the first-century counterpart to that activity was” (p. 85). Indeed, Paul is no solitary genius without friend or collaborator.

The book on Paul by Keck and Furnish complements those of Marrow and Bruce by asking the vital question: How does one interpret Paul, his letters and theology in a contemporary situation? Keck and Furnish present their substantial fare in an appealing way. Chapter 1 makes a very illuminating distinction between the public Paul (Paul as viewed in the public eye as a misogynist), the scholars’ Paul (Paul as collaborator with women in evangelization) and the Church’s Paul (Paul as Saint and as the Apostle). Chapter 4 is given over to Paul as interpreter of the Christ-event, of ethical traditions, of the Spirit and of Scripture. In chapter 5 the authors treat the disputedly genuine Pauline letters—2 Thessalonians, Colossians, Ephesians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus—under the rubric of “the Pauline tradition interpreted.”

For readers seeking updating on Paul, this slender volume will be challenging. But the effort will be richly rewarded, for on many a page gems of insight shine forth. For example, “Paul is a coherent writer but not a systematic one. Consequently he does not discuss topics in a logically ordered sequence” (p. 64); “… Paul does not interpret the gifts (of the Spirit) but the situation in which the gifts are exercised” (p. 99).

006

Beautiful Biblical Texts

Doorposts

Timothy R. Botts

(Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House, 1986) 121 pp., $19.95

Calligrapher Timothy R. Botts brings to life a collection of biblical passages through his sensitive artistic renderings of the texts. Botts gives immediate meaning to the biblical text by using a vast of assortment of calligraphic letter forms, brush techniques, color and layout; his skillful arrangement of the letters into shapes such as a wave, a funnel or a cloud contributes to establishing the mood of the quotation. Facing each page of biblical text are Bott’s personal notes that help us to understand how and why he created each rendering.

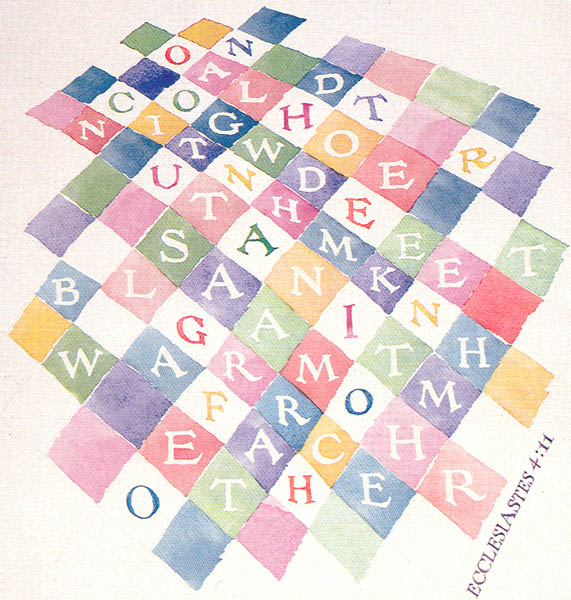

We see Bott’s technique displayed beautifully in Ecclesiastes 4:11: “On a cold night, two under the same blanket gain warmth from each other.” The calligraphy depicts a handmade quilt with letters in its squares, communicating the warmth that two people could share under such a blanket. The loose informality of this graphic with its attached folding squares gives a feeling of warmth and hominess of the text.

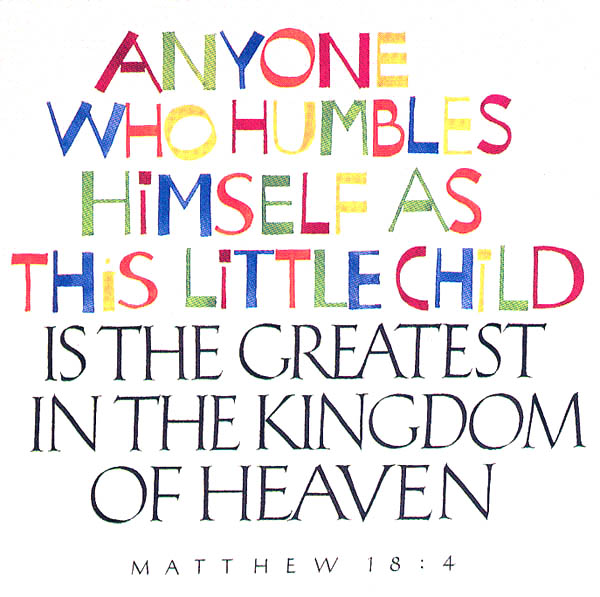

Matthew 18:4 informs us that “Anyone who humbles himself as this little child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven.” Botts uses two types of letter forms—a colorful Ben Shahn childlike alphabet for the humbleness of a child and an elegant formal Roman face for the last half of the quotation referring to the greatness of the kingdom of heaven.

The only addition that might have enhanced this beautiful collection of biblical passages would have been use of Hebrew as a decorating motif in conjunction with the English texts. Hebrew, as well as English, has many beautiful alphabets that could contribute to the various moods of the texts.

For appreciators of biblical text, for students of calligraphy or Just for those who like to see beautiful and interesting letter forms come alive, I suggest that you walk in between the Doorposts. It is truly a masterful creation.

Jesus and the Spiral of Violence: Popular Resistance in Roman Palestine

Richard A. Horsley

(San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987) 355 pp., $27.95

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

The Five Scrolls has been published in three editions: The congregational edition (reviewed here) includes both the translation of the five books and prayers to accompany the reading of the books in the synagogue on the holidays when it is traditional to do so; the next version, without prayers, in a larger format than the congregationnal ($60), and the special limited edition in large format printed on rag paper with a hand-pulled Baskin etching, signed and numbered by the artist ($675). In all three versions, Baskin’s 37 watercolor illustrations are included.