Bible Books

014

David’s Social Drama: A Hologram of Israel’s Early Iron Age

James W. Flanagan

(Sheffield, England: The Almond Press, 1988) 373 pp., $22.00

This is an important but difficult book. One might almost call it two books, not because of excessive length, but because it unfolds on two levels. James Flanagan uses several complex social-scientific models in his carefully crafted interpretation of the slow emergence of Israel in the early Iron Age and of its precarious but brilliant consolidation under King David. Unfortunately, he disconcertingly mixes the presentations of the models and their methodological implications with specific hypotheses about early Israel, resulting in a book that must be “chewed over” every step of the way. The work’s distinctive strength in content, however, compensates for its weakness of form. For the patient and consistently attentive reader, the interplay of method and hypothesis proves highly rewarding in the end, even though the payoff may seem long delayed.

Flanagan starts from the widely shared consensus that we do not possess enough information about early Israel to write a detailed sequential history. He contends, however, that we can construct “maps” of the crucial ecological, sociopolitical and religious developments leading up to David if we make judicious use of the archaeological and biblical data, each at first examined and synthesized independently of one another. These developments can in turn be read intelligibly within models of comparative sociology. For example, Flanagan is particularly impressed by the analogies between David and Ibn Saud, founder of modern Saudi Arabia, as chieftains who unified far-flung, segmented groups into large political entities. He calls this kind of cautious historical reconstruction a “hologram,” by analogy with laser-based technology that is able to produce lifelike, three-dimensional images. His case for this metaphor is intriguing but somewhat strained and may cause as much confusion as illumination. The chief value of the metaphor is to underscore the idea that a reconstruction of early Israelite society and religion is not like taking a photograph or piecing together a jigsaw puzzle but is rather a work of controlled imagination that integrates disparate kinds of converging and diverging information.

Readers of BR are likely to be most interested in Flanagan’s conclusions. He pictures early Israel as a segmented social system of balanced and more or less equal parts, lacking a centralized political apparatus. Its members occupied varied economic niches in seafaring, trading, agricultural and pastoral pursuits. This Israel only slowly differentiated itself from other inhabitants of the area. Its distinctive Yahwistic religion provided an integrating ritual focus, as it also drew freely on other religious ideas and practices in the environment. Israel’s fortunes waxed and waned until a firmer identity and cohesion were achieved under David, who was much more a paramount chief than a king, as shown most vividly in his refusal to build a temple or to develop a large bureaucracy. Operating from a pastoral base in Judah, David was able to gather together and represent the interests of the diverse segments of Israel and also of many non-Yahwists in the region. The structures of full-blown monarchy and dynastic succession, often erroneously associated with David, came into being only after David’s reign.

This work is crammed with rich and provocative detail, which will be long debated. The author makes it commendably clear why he offers plausible hypotheses and not “hard facts.”

The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel

Mark S. Smith

(San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990) 197 pp., $26.95

Who is the God of ancient Israel? Where did He (or She?) come from? Is God always the same in the biblical writings, or is there a diversity of concepts of God? If there is a diversity, how do we explain it? These and similar questions have nagged at biblical scholars for centuries. Often scholars have tried to avoid these questions, being content with the thought that God is always God, even if humans tend to perceive Him (Her?) in limited ways. In the last century or so, however, archaeological discoveries have led scholars to reconsider the nature and origins of Israelite ideas of God in comparison with the gods of the newly recovered cultures of the ancient Near East.

The most important discovery in this new search for the history of God was the 015excavation of a library of clay tablets found in the ancient Canaanite city of Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra, in Syria). These tablets, first discovered in the early 1930s and deciphered shortly thereafter, were written in a Semitic language that we call Ugaritic, which was a near relative of ancient Hebrew (sort of an uncle to Hebrew in the linguistic family tree). The Ugaritic tablets come from around 1300 B.C.E., and they show us a picture of Canaanite culture and religion only a century or so before the Israelites arrived on the scene in the highlands of Southern Canaan (about 200 miles south of Ugarit).

Since the 1930s, biblical scholars have learned that the Canaanite texts shed considerable light on the early Israelite concept of God—that the Canaanite gods such as El (the creator-god and patriarch), Baal (the warrior-god), Asherah (the mother-goddess), Anat (the warrior-goddess) and others have many traits that were shared by the Israelite god, Yahweh. Just to give a sampling of examples: Yahweh shares many of the titles and roles of the earlier Canaanite god, El—Yahweh is called “El, the God of Israel”; he presides over the divine council of the “Sons (or Children) of El”; he is wise and compassionate, the creator of the world, the creator of humans, and more. Like Baal, Yahweh is called the “Rider of the Clouds” and is described as a warrior-god, defeating sea-monsters such as Leviathan and Sea at the dawn of time. Baal is also presented in the Bible as a rival god to Yahweh during the time of Ahab and Jezebel and later. The Bible also mentions the worship of the goddess Asherah and a cultic object called “the asherah”; occasionally Yahweh is described with female imagery, as when Yahweh pants and screams “like a woman giving birth” (Isaiah 42:14). All of these are traces of the legacy of Canaanite religion on Israelite religion. The recovery of the Canaanite pantheon shows us the source of many of the Israelite concepts of Yahweh.

In The Early History of God, Mark Smith attempts a synthesis of our current understanding of the history of the Israelite concept of God. He begins by explaining the Canaanite heritage of Israelite religion and then proceeds to uncover the legacy of the chief Canaanite gods—El, Baal, Anat, Asherah and the Sun—in the Israelite concept of Yahweh. Smith then discusses various Israelite ritual practices (including rituals for the dead and child sacrifice) in their Canaanite context. He concludes by sketching the history of Israelite monotheism. Smith covers a lot of territory in these chapters, and he does it in splendid fashion. While certain parts may be overly technical for some readers, he has kept in mind the general reader and guides us along with a sure hand. The book is well written and consistently insightful, and it shows a fine sense of judgment. An enormous amount of research has gone into this book, yet the final product is elegant and enlightening.

As his subtitle suggests Smith is walking in the footsteps of William F. Albright (author of Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan), and also in the path of his teachers, Frank M. Cross and Marvin Pope, who have made many contributions to our understanding of the Canaanite heritage of Israelite religion. Smith’s well-wrought synthesis is informed by deep learning, maturity of judgment and an obvious passion for the subject. Old Man Albright would certainly be proud.

The Faces of Jesus

Frederick Buechner (text), Lee Boltin (photography) and Ray Ripper (design)

(New York: Stearn; San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1989) 256 pp., $19.95, paperback

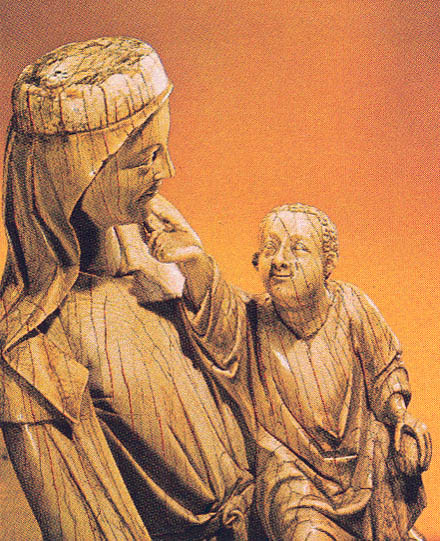

To review this handsome book is a singularly difficult assignment for me because it satisfies and disappoints at the same time. One hundred fifty-four stunning color plates show the image of Christ as depicted by artists for the past 1,400 years—artists from Melanesia and Africa, Russia and Yugoslavia, Sweden, Japan and China—artists who worked in mosaic, wood, bronze paint, cloisonne, fresco, embroidery, straw, and, yes, even as designers of banners. The photographer of these works, Lee Boltin, is a skilled professional, with a tremendous flair for sculpture in particular. He chooses unusual angles for the carvings and bronzes of Christ on the cross, and his dramatic lighting plays across the craggy features of these suffering Christs and dances 052along the narrow, stark rib cages of their attenuated bodies. We look sharply up upon a face of Jesus, where we note that life seems to have just this moment ended. And we look down upon the face of the Christ Child (see photo, above) who, smiling, reaches playfully to touch the Virgin’s chin (a gesture Leo Steinberg has dubbed “the chin chuck”).

These beautiful photographs bring us close in upon the work of art. In the case of the Virgin and Child noted above, we are brought closer to the texture of the ivory and details of the Virgin’s lovely French face and smiling eyes and lips, to the child’s extended hand so skillfully modeled and to the graceful folds of their garments, which enframe this mother and child—all of this wealth of beauty and tenderness is made accessible to us in a way that even seeing the original might not. The Virgin and Child is in fact tiny, and if seen along with many other carvings in its case at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, we could not experience it as we do in the photograph, which gives an enlarged detail of this tender twosome.

For me, however, the choice of works of art is not entirely successful. I applaud the wonderful images from the Carolingian and Romanesque periods, and the inclusion of the strange and little-known mosaic of Jesus, with its square beardless chin and penetrating dark eyes (dated to the sixth or seventh century, from Hinton St. Mary), now in the British Museum.

But the 20th-century examples are deplorable. They consist of works of artists of limited vision and skill (Watanabe, Buffet, Corita Kent) and children’s drawings. These latter tell us something of the child’s imagination but are wholly inappropriate in the company of the profoundly felt works of mature artists. Great artists of our century have given us profound and memorable “faces of Jesus”—Matisse, Picasso, Moore, Nolde, Zorach to name but a few. None of these is among the 154 plates of this book.

Furthermore, the architects of the book have eschewed art of the Renaissance; thus Giotto, Fra Angelico, Donatello, Botticelli, Leonardo and Michelangelo are omitted, as are Titian, Caravaggio and Rembrandt. Perhaps the intention was to avoid the great artists who have given us the famous “faces of Jesus.” This intention might account for the fact that the most famous work included is labeled simply “Spain, 17th century”; it is in fact by Velasquez.

The text by the well-known American writer and cleric, Frederick Buechner, consists of six well-crafted homilies on the life of Jesus, dealing with the Annunciation, Nativity, Ministry, Last Supper, Crucifixion and Resurrection. He eloquently asks that we see “this extraordinary man [and that we] read the New Testament with not just our eyes but our hearts and imaginations open.” The text weaves back and forth between biblical quotations and interpretations, and meditations on the plates of the book.

The striking plates will certainly excite a conversation between the attentive reader/viewer and these faces of Jesus. It would be gratifying if this book were to stimulate studies on the faces of Jesus as expressions of the imagery and theology of successive historic periods. But, for me, the selection of plates should be edited and others added while retaining the superb photographic quality.

David’s Social Drama: A Hologram of Israel’s Early Iron Age

James W. Flanagan

(Sheffield, England: The Almond Press, 1988) 373 pp., $22.00

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.