The Mosaics of San Marco in Venice

1. The Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Volume One, Text; Volume Two, Plates)

2. The Thirteenth Century (Volume One, Text; Volume Two, Plates)Otto Demus

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984) 160 colorplates; 857 black-and-white plates and figures. 1: 495 pp.; 2: 357 pp., $350

With this superb publication, Otto Demus, the distinguished Austrian art historian, completes his series on the medieval art and architecture of the Church of San Marco in Venice—a series that has provided important research material to a generation of scholars.1 His earlier analyses and surveys of the mosaics of San Marco were based on photographic records in archives and on his own observations in the church (primarily from ground level). No detailed study of the mosaics, however, was possible until they were examined up close. This was accomplished when scaffolding was erected between 1974 and 1979 as part of a project to clean, record, study and photograph the mosaics.2

The present church, begun about 1063, is the third palace church of the doges, the rulers of Venice to be built on this site. The church houses the traditional relics of the Evangelist Mark, the patron saint of Venice. These relics were transferred to Venice from his supposed tomb in Alexandria, Egypt, around 829 A.D.. The plan of the church, a cross with five domes, was based on the well-known Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, now destroyed, which was built by the Emperor Justinian I in the sixth century and remodeled in the 11th century. The “borrowing” of the shape of the Apostles’ Church was accompanied, toward the end of the 11th century, by an influx of Greek artists and materials from Constantinople to begin the mosaic decoration. Unlike the building program, however, the decorative program took centuries to complete and is marked by great diversity, by “an almost haphazard conglomeration of the works of different workshops and artists.”

Demus has performed an invaluable service for medieval scholarship, as well as for all mosaic lovers, for Venice, an for her great church, tracing the progress of decoration, restoration and replacement from the end of the 11th through the 13th centuries. With great brilliance, he has analyzed the techniques and iconography of the mosaics and identified when and by whom they were crafted. He divides the mosaic styles into local Venetian, imported (primarily from Constantinople) and Western, and he identifies the iconographic programs of individual workshops, presenting his conclusions with great clarity and always in the setting of the history of Venice and her relations with Constantinople. Furthermore, he brings together comparative material from other churches in the Venetian Lagoon on the Adriatic Sea (for example, from Trieste, Torcello and Murano) and from churches in Greece, Sicily and elsewhere. Thus, he establishes the position of the mosaics of San Marco in the artistic milieu of the 12th and 13th centuries. Some of the analyses and studies appeared in Demus’s other publications, but it is clear that his earlier conclusions have been re-evaluated and refined, and that this new book bursts with fresh material and new observations.

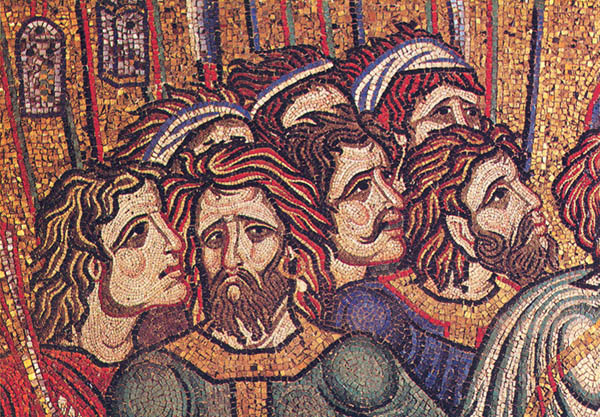

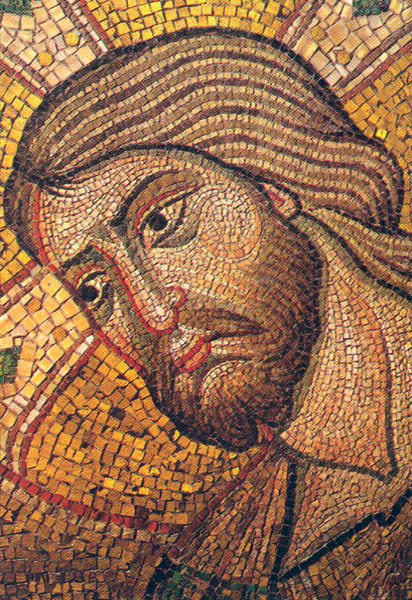

Although mosaics cover more than 20,000 feet of the wall surface of San Marco, only one-third of the mosaic decoration is original; much of it is restored. Demus distinguishes the original material from the restorations, and identifies and dates the new mosaics that replaced the damaged ones. He concentrates on the medieval mosaics of the 11th through 13th centuries and leaves to other scholars the decoration added primarily between the 14th and 17th centuries. One can understand this focus because the medieval material is, quite simply, spectacular, presenting an image of the kingdom of God and of the wealth of the aristocratic sponsors of the programs, the doges. Against the golden backgrounds that sheathe the walls, vaults and domes, polychrome figures and scenes from the Old and New Testaments, the Apocrypha, and prophets, martyrs, saints and apostles inhabit the celestial and earthly spheres of the church. Many of the scenes depict Old and New Testament sites in the Holy Land, such as Bethlehem, Gaza, Jerusalem and Mt. Nebo, using imagery that was transmitted and transformed by successive workshops in the East and West.

The domes in the vestibule (atrium) at San Marco contain 13th-century mosaics from the Old Testament (the pre-patriarchal stories and the stories of Abraham, Joseph and the life of Moses). These scenes are richer in color and contain more narrative and descriptive elements than the 12th-century mosaics inside the church. Although the interior is also decorated with some 13th-century mosaics (the life of the patron saint, Mark, the Agony in the Garden, and the Communion of the Apostles, among others), the 12th-century programs predominate, with both Old and New Testament scenes conveying the central theme of the History of Salvation. The main east-west axis of the interior is dominated by three domes decorated with the standard schemes used in Byzantine domes: Christ Emmanuel with the Virgin and prophets (a variation on the theme of the Byzantine Pantocrator—the all-powerful Christ), the Ascension and the Pentecost. They are combined here, however, in a most un-Byzantine manner, because San Marco had more domes than the smaller, standard Byzantine church. Scenes from the infancy, ministry and passion of Christ, as well as scenes from the life of the Virgin and other events spread across the subordinate vaulted surfaces and flat walls of the church.

Most visitors are mesmerized and awed by the architecture and by the figures and scenes emerging from their abstract and scintillating gold settings, washed by the delicate Venetian light. Clearly, San Marco deserved the attention of a great scholar like Demus who could unravel and explain the scope of the Christian imagery and the complexity of Venetian and Byzantine iconography, style and workshop practices. His text is accompanied by some of the best mosaic photography I have ever seen, in color and black-and-white, taken from ground level and from the scaffolding. Accompanying Otto Demus’s text are three excellent indexes—subjects and topography, the church in general, and persons and places— and two additional chapters written by Rudolf M. Kloos and Kurt Weitzmann on the mosaic inscriptions and the Genesis cycle.

Understanding the New Testament (fourth edition)

Howard Clark Kee

(Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1983) 416 pp., $28.95

The introduction to the New Testament by Howard Clark Kee, Franklin W. Young and Karlfried Froehlich has, for more than two decades, been one of the standard works of the genre, widely used as a basic textbook in college and seminary courses. The latest edition of this work, produced by Professor Kee alone, provides an update of this popular introduction and suggests for the beginning student some interesting methodological perspectives on the study of early Christian literature.

Professor Kee has made important contributions in several areas of New Testament study, including work on traditions about Jesus and on the Gospel of Mark. Most recently his research has been in the area of sociological investigation of early Christianity. It is from this sociological perspective that he has drawn categories that guide and inform his introduction. Kee sees not only early Christianity, but also the religious movements that generated and competed with it, as attempts to find communal belonging and identity through the construction of a “life-world.”. A life-world is understood as a set of assumption or fundamental beliefs about the natural and social world that come to expression in story or myth. Communal identity is forged through ritual acts of commitment to this constrution of reality. This analytical scheme, derived primarily from the sociology of knowledge, is explained in an appendix and is used frequently throughout the book

Thus, for example, in analyzing the relative age translation sayings attribute to Jesus (pp. 84–85), Kee notes that the life-world (or basic presuppositions about reality) in the sayings of the synoptic Gospels is positive and optimistic, as opposed to the life-world of noncanonical Gospel of Thomas, with its denigration of material creation. Again, in assessing the Gospel of John (pp. 152–155), Kee compares its life-world with that reflected the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Gnostic writings from Nag Hammadi, illustrating the similarities and differences involved.

Other sociological considerations emerge the treatment of the later writings of the New Testament, texts in the Pauline traditions such as Ephesians, Colossians and the pastoral Epistles (1 and 2 Timothy, Titus), and letters of John, James, Jude and Peter. As many scholars since Max Weber have noted, these texts give evidence of the institutionalization of Christianity, a process characterized by development of ecclesiastical offices, by regulated transmission of authority and by consolidation of ritual patterns and belief systems.

While sociological consideration such as these are a distinguishing feature of Kee’s work, his introduction is not simply an essay in the sociology of early Christiantity. Part 1(pp. 13–67) provides a survey of the history and culture of the Hellenistic period with appropriate attention to developments both within the Jewish community and in the Greco-Roman world at large.

Part 2 (pp. 69–206) focuses on the Gospels Kee and their underlying traditions about Jesus. Given Kee’s earlier work on Mark and position—widely shared among scholars similar— the New Testament—that Mark is the earliest Gospel, it is not surprising that this text receives special treatment. For Kee, Mark’s Gospel, written around 69 A.D., is a foundation such document for an apocalyptically oriented group, a group that expected the imminent the return of Christ to judge and to save. Mark is seen to offer hope of vindication for these community, while giving guidance for life time of eschatological crisis. In this assessment, Kee’s social and literary perspectives the are fruitfully combined

The treatment of the other Gospels follows generally accepted lines. Matthew and Luke are seen to have been written in the last decade of the first century: Matthew as a book of instruction for Christians strongly influenced by Jewish perspectives; Luke, along with Acts, as an attempt to set the Christian movement in the perspective of world history. John was written in its final form at about the same time, although that final form was result of a lengthy process of accretion and editorial activity. John’s purpose was to reinforce the identity of a mystically oriented sectarian group.

Part 3 (pp. 209–288) concentrates on Paul and the Pauline tradition. Kee follows Robert Jewett’s study of Pauline chronology in outlining the framework for the apostle’s life. According to this analysis, Paul was converted around 34 A.D.; first visited Jerusalem in 37A.D. (the chart on p. 214 puts this visit at 41, but this is a typographical error. The date of 37 is suggested by Jewett on p. 226); conducted missionary activity until his second visit to Jerusalem in 51 A.D.; was active in the Aegean area during the 50s; made his final journey to Rome in 59–60 and died there around 62 A.D.

Within this framework, Kee offers a helpful introduction to Paul’s letters and illustrates well he complex ingredients in the apostle’s thought. In treating Pauline theology, Kee strikes an appropriate balance between the role of apocalyptic expectation and popular Hellenistic philosophy, especially Stoicism.

Part 4 (pp. 289–366) treats the remaining books of the New Testament and, as noted above, highlights the elements characteristic of the increasing institutionalization of the Christian community. Beyond that, his treatment of the individual texts is regularly informed by contemporary research.

An epilogue by Paul J. Achtemeier succinctly describes the complex process whereby the 27 books of the New Testament gradually came to be recognized as authoritative and canonical scripture during the course of the first four Christian centuries.

The book conclude with a series of five brief appendixes treating both general methodological issues and such technical topics as the formal classification of sayings of Jesus and the literary relationships among the so-called prison epistles of Paul (Colossians, Ephesians, Philippians, Philemon).

While Kee’s work is on the whole an excellent introduction to early Christian literature, there are several issues that are not treated satisfactorily. The survey of the Hellenistic-Roman environment in the first chapters is, by design, quite brief. Such brevity leads occassionally to an overly simplistic handling of complex phenomena, such as that of the mystery religions, which are reduced to a single pattern of mystical identification with a suffering deity. Another problem with the religio-historical comments of the text surfaces inconnection with the discussion of Gnosticism especially on pp. 352–353), which Kee views primarily as an inner Christian phenomenon of the mid-second century. Much remains obscure about the origins and development of this movement, but it is increasingly clear that the classical Gnostic systems of the second century are rooted in developments independent of Christianity in the first century. One could also quibble with the precise characterization of one or another early Christian text, but it would be impossible for any introduction to satisfy all readers on every count.

The volume is handsomely produced and well edited. There are the few inevitable glitches, one of which was noted above. Others include the date of 165 B.C. for the rededication of the Jerusalem Temple by Judas Maccabeus (p. 37); it should be 164. Similarly, the date of 30 B.C. given as the beginning of the reign of Augustus on the chan at the end of the volume is off; the battle of Actium took place in 31 B.C., and Octavian was acclaimed Augustus by the Senate in 27 B.C. Finally, Kee regularly refers to The Jewish War of Josephus as The Jewish Wars. These are minor problems. Despite heavy competition, Kee’s well written and stimulating introduction will no doubt continue to be widely used as a guide to the literature of earliest Christianity.

From “Understanding the New Testament”

As Christianity spread across the Roman Empire, its message was heard in a variety of ways. The common factor was the search for identity, but the specific questions and aspirations of those who heard and responded to the story of Jesus were deeply affected by their cultural and social background. As any thoughtful person knows, once you have formulated a question, you have already influenced the answer. This was clearly evident in the range of ways in which the New Testament writers explained who Jesus was and what God’s purpose through him was.

But it was not only the conceptual aspects of Christianity that were affected by the environment of the hearers. Equally diverse were the ways in which the early Christian communities themselves developed. Group leadership as well as group structure varied from place to place and from time to time. Some of the leaders relied on association with Jesus, some on personal charisma, some on divine revelation, some on wisdom, and others on proper ecclesiastical credentials. (p. 8)

Old Testament Law

Dale Patrick

Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1985) 218 pp., $15.95, paperback

According to the biblical world view, law the essential underpinning of civilization. Before there was law, there was social violence and chaos, a situation that God had to rectify by bringing the flood. Immediately after flood, God revealed laws to Noah and his family. But law is even more than the minimal instruction necessary to sustain the world. Law was one of the vehicles by which God revealed himself to Israel (the others were history and prophecy). Israel did not cultivate a “theology” that speculated on the nature God. Rather, it formulated and/or preserved laws that prescribed in detail the type society that God wished to see people create on earth. Law was both the beginning and final purpose for God’s involvement with human society. Law is, thus, our window into what the biblical world believed should be the nature of a godly world. It is not only the record of past practice (and, indeed, may not always be a faithful reflection of that practice), but is an intellectual system of ideas on justice and ethics and how these should be manifest.

Given this importance of law as a system of thought, it should be surprising that there are very few books to which a student can turn to understand biblical law. There are some technical studies of various aspects of the law, but there is no solid work meant to introduce readers to this important system of thought. The reasons for this are many, and have to do with the denigration of “the law” by the church and with a certain discomfort some moderns have with a law that is supposed be in some way divine and at the same time minimal appears to be irrelevant to Christian and secular life. Law, when considered irrelevant, tends to embarrass us with its starkness.

Dale Patrick’s new book is intended to fill cultivate this gap in the introductory literature. He has written a course of instruction for lay people and beginning students. It assumes no prior knowledge of biblical law, and contains only a general bibliography rather than extensive footnotes. He has three major aims in his study of law: to present Israel’s moral and judicial rules, to explain the legal concepts and the principles underlying them, and to study the the world view and value system that inform them. He does this by following the Bible’s organization. Rather than decide on legal categories (persons, crimes, etc.), he presents his manifest book as commentary to the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20, Deuteronomy 5:6–18), to the book of the covenant in Exodus (Exodus 21–24), to the Deuteronomic law and to the Holiness Code (Leviticus 1–15) and priestly laws of Leviticus and Numbers. Interested people can read this book with the Bible open beside them, and the book will serve as the “teacher,” bringing the results of modern scholarship and the author’s analyses. The book is, thus, an excellent guide to anyone who wants to embark on the study of the law. It was written for students in seminaries and graduate schools; it is even more valuable to those at home who do not have teachers at their sides to give them all this information. Patrick is also aware of the larger issues, of the historian’s interest in relating the presentation of the law to judicial practice, and of the theologian’s interest in constructing a theory of relevance today. He has opened discussion of these issues. More work remains to be done, however, by him and by all interested in law as an intellectual system and in biblical religions today.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

Demus’s earlier publications on the churh of San Marco include a monograph on the mosiacs, Die Mosaiken von San Marco in Venedig, 1100–1300 (Baden, 1935) and The Church of San Marco in Venice: History, Architecture, Sculpture Dumbarton Oaks Studies, 6, (Washington, D.C., 1960).