Bible Books

010

Torah as Therapy

Self, Struggle & Change: Family Conflict Stories in Genesis and Their Healing Insights for Our Lives

Norman J. Cohen

(Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing, 1995) 209 pp., $21.95

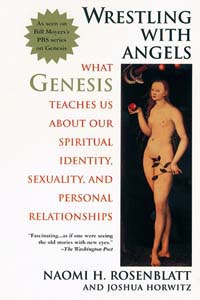

Wrestling with Angels: What Genesis Teaches Us About Our Spiritual Identity, Sexuality and Personal Relationships

Naomi H. Rosenblatt and Joshua Horwitz

(New York: Delta, 1996) 386 pp., $12.95 (paper)

Both of these books share the conviction that the Bible contains wisdom both applicable and necessary for solving today’s problems, despite the fact that these solutions have been largely overlooked in secular society. The authors propose, explicity or implicity, midrash as a mode for uncovering the psychological teachings of the Bible. Naomi Rosenblatt.1 a psychotherapist, alludes to the midrashic approach without specifically naming it: “In narrating the story of Genesis we have followed the example of rabbis and poets of every generation who have added narrative details to the original canon as a way of fleshing out its often sparse outlines.” Norman Cohen, who is a professor of midrash at Hebrew Union College—Jewish Institute of Religion, in New York, defines the midrashic tradition as “the attempt to find contemporary meaning in the biblical text. The term midrash comes from the Hebrew root darash which means to seek, search or demand.”

One convincingly nuanced reading by Cohen that draws on midrashic sources is his suggestive portrait of Leah as “sensitive and kind” and as a woman whose “purity of spirit is deemed more substantive” than Rachel’s “barren” beauty. While he cites some lovely interpretations that focus on Leah’s efficacy and innovation in prayer, he wrenches the text to read Rachel’s infertility psychologically, representing her as “‘being void’ of concern and sensitivity,” ignoring the tradition of Rachel’s supplicatory power: “A voice is heard in Ramah…Rachel is weeping for her children” (Jeremiah 31:15).

The main theme Cohen sees in Genesis is the repeated conflict of opposites within and between individuals. This may be a useful way of thinking about Genesis; its application to contemporary conflicts, however, ranges widely from the personal to the social and political: parent-child relations, sibling rivalry—with repeated emphasis on challenges faced by blended families—homelessness and Palestinian-Israeli relations.

Rosenblatt, on the other hand, brings her psychological training to bear in her retelling of Genesis to present a more comprehensive and interesting discussion of contemporary issues—not always with satisfying results, however.

Her analysis of Jacob’s relationship with his parents, Isaac and Rebecca, represents the family as deeply dysfunctional; but by focusing on the family dynamic, Rosenblatt loses sight of the larger pattern of ethical concern in Genesis (and Exodus, for that matter): the repeated preference for the younger son over the older as a critique of physical power. The system of primogeniture is undermined by the text’s refusal to transmit paternal authority to murderous, physically threatening or lawless older sons: Cain, Ishmael, Esau and, to a certain 012extent, Reuben, Simon and Levi.

While both authors present genuinely penetrating readings of Genesis, they often flatten and simplify their interpretations to permit pragmatic suggestion. This is not to say that the Bible holds no contemporary significance; individuals can find valuable personal insights by reading and thinking deeply about biblical texts. But when biblical authority is harnessed to the insights of a specific individual, no matter how gifted, who presents these ideas as generally applicable therapeutic advice, I question the benefit. I admire these authors’ love for and years of study of Genesis, and applaud their exhortation of contemporary readers to take the Bible seriously as a source of wisdom and inspiration. Nevertheless, I worry that their psychological readings of such a rich and elusive text might inhibit readers from bringing different but equally valid and valuable personal perspectives to the text.

The Truth About the Virgin: Sex and Ritual in the Dead Sea Scrolls

Ita Sheres and Anne Kohn Blau

(New York: Continuum, 1995) 236 pp., $27.50

A book about gender in the Dead Sea Scrolls is long overdue. For many years, the scholarly consensus that Qumran (where the scrolls were found) was inhabited by an isolated Jewish sect of celibate “monks” made the subject of gender, and particularly the female gender, peripheral at best. With that consensus increasingly called into question, more writers are discovering material about women in the scrolls (see, for example, the excellent work of Eileen Schuller). A book that brings this material together is therefore very desirable. Unfortunately, this is not the book.

Authors Sheres and Blau fall into an all-too-common trap among interpreters of the scrolls: They assume that something mysterious or esoteric lies hidden in the scrolls and needs to be uncovered. 014They begin with several chapters of introductory material explaining the corpus of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Greco-Roman cultural milieu and its misogyny. These chapters are well researched and documented, although I did find it disturbing that the authors do not differentiate between various “schools” of scroll scholarship. It is unusual, to say the least, to find Robert Eisenman and Lawrence Schiffman footnoted in the same paragraph, as if their conclusions concerning the scrolls were in any way compatible!

It is in the later chapters that Sheres and Blau embark on their dangerous journey into the realm of speculation. Their main thesis, contained in chapters 4 through 7, is that the male covenanters at Qumran practiced an elaborate ritual of castration, which left them incapable of participating in sexual acts, any and all of which the sect considered polluting.

However, since the sect was also eager to bring about the birth of the messiah, they engaged in a parallel ritual: the artificial insemination of a young virgin girl with semen from a chosen male member of the sect. They base these rather astonishing conclusions on an interpretation of a supposed “secret ritual” described in the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice (4Q400-405, 11Q17) and another “secret ritual” discovered in 4Q502, a Ritual of Marriage. In no way do the authors offer any convincing proof for their speculations. In both cases, the material can be adequately explained as liturgical texts accompanying worship and marriage (as Carol Newsom has done in her edition of the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice). There is no justification for forcing an esoteric interpretation upon these texts: there is enough unclarity in even the most banal interpretation to keep researchers busy for a long time to come.

Though it addresses a worthy topic, The Truth About the Virgin is not a work of serious scroll scholarship.

Children of the Alley

Naguib Mahfouz

(New York: Doubleday, 1996) 449 pp., $24.95

The people live in squalor along the narrow streets of the alley. Local gangsters beat them and demand protection money, while the corrupt overseer siphons off the income from the mansion at the end of the alley. Why do these injustices prevail? Ask the awesome ancestor of the alley who lives in the mansion, but whom no one has seen since the days of the great men of the alley’s past—Adham, Gabal, Rifaa and Qassem.

Who are these great men of the alley’s past? None other than Adam, Moses, Jesus and Muhammad. Who is the ancestor, so distant, feared and loved? He is called Gabalawi, “the Mountain Dweller,” but is better known to us as God Most High. Where is the alley? Egypt—and everywhere.

In this sublime novel, Naguib Mahfouz, winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1988, has crafted a wondrous and tragic story of the alley that resonates with the drama of the Bible. The story is told in a mesmerizing style that blends the natural and the supernatural, creating an effect that recalls the modern realist novel and The Thousand and One Nights. Mahfouz is an Egyptian, writing in Arabic, and seems 016to have found a new way of retelling the old, sacred stories.

These beautiful tales of Adham, Gabal, Rifaa and Qassem and their encounters with the gangsters and the mysterious ancestor originally appeared in serial installments in a Cairo newspaper in 1959. The public was so shocked and the local religious authorities so outraged that no Egyptian publisher dared to publish it (an expurgated Arabic edition was published in 1967 in Lebanon). Mahfouz still receives death threats from Muslim fundamentalists nearly 40 years later. Mahfouz is the original Salman Rushdie, but Mahfouz is the greater writer, and this is one of his truly great books.

The storytellers tell their stories each night at the coffeehouses of the alley. The people of the alley love their stories and can never hear them enough. Perhaps another great one will come, inspired by the stories, and defeat the gangsters once and for all, returning them to the ways of Gabalawi and his chosen ones. Perhaps they may even realize the unfulfilled dreams of Adham after he was expelled from the mansion. The people’s lives are harsh, but no one can extinguish their hopes, which are nourished by the wondrous stories of the alley’s past.

The Mystery of Romans: The Jewish Context of Paul’s Letter

Mark D. Nanos

(Minneapolis: Fortress, 1996) 448 pp., $25

Mark Nanos proposes a provocative new reading of Romans that describes “a thoroughly Jewish Paul, functioning entirely within the context of Judaism.” The book is a bold revision of the usual view of Paul’s mission and the social settings of the communities he founded and/or nurtured.

Like many recent interpreters Nanos reads Romans as a letter that addresses specific Jew/gentile issues in Rome. Howeve, for Nanos, it is the relation of Christian gentiles to non-Christian Jews that Paul is concerned about, not their relation to Christian Jews, as many hold. Nanos’s interpretation of Romans is based on the premise that Paul’s ministry and even the churches he planted operated entirely and unambiguously in a Jewish context, under the authority of Jewish synagogue leaders. The letter to the Romans was occasioned when a minority of Christians gentiles-misguided 053by what Nanos identifies as the libertines of Romans 16:17–20-threatened to reject Jews and the behavorial norms Jews expected of “righteous gentiles.” Paul confronted this development in Romans lest the Jewish community (or communities) reject the Christians prior to Paul’s arrival. If that were to happen, the apostle would not be able to preach in the synagogues and fulfill the “divine two-step pattern” (offering the gospel to Jews before gentiles) required for the restoration of Israel and the fulfillment of his mission.

Nanos’s book is an extension of a trend that has been developing in the study of Romans-and in Pauline studies more generally—for decades now. Krister Stendahl, with his 1963 essay “Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West,” inaugurated the search for a less “Lutheran” Paul. Another scholar, E.P. Sanders, has played a leading role in freeing Paul from reformation dogmatics and positioning him in his own Jewish context. The interpretive trend that finds a more “Jewish” Paul in the context of a less “legalistic” Judaism has come to be called the “New Perspective” on Paul. Nanos thinks that Sanders was successful in freeing Pauline exegesis from its “sixteenth-century blinkers,” but he does not think Sanders has described a Paul who would have made sense to his fellow Jews. It is this deficiency that Nanos intends to correct.

Nanos first introduces the reader to an overview of the book’s argument and Paul’s purpose for writing. He then focuses on the situation in Rome, especially on the relation of Christian gentiles (and of Jews) to the Jewish community(s) in Rome. Nanos argues that the “weak” in Romans 14:1–15:13 are not Christian Jews who continue to observe ritual purity laws but rather non-Christian Jews who are labeled “weak/stumbling” because of their lack of faith in Jesus as Christ. He next explores the phenomenon of “righteous gentiles” and the behavior that was expected of them by Jewish communities and then investigates Paul’s view of the restoration of Israel and its relation to his missionary plans for Rome. In his final chapter, Nanos suggests that Romans 13:1–7, on obedience to governing authorities, refers not to Roman rulers, as is usually held, but to Jewish synagogue leaders.

There are a number of fascinating and controversial aspects to Nanos’s study. First, it is one thing to locate early Roman Christians unambiguously in Jewish synagogues. It is another, however, to suggest that this pattern reflects the typical way Paul and Pauline communities operated vis-à-vis Jewish communities. In recent years scholars typically have been impressed by the lack of evidence in Paul’s letters for interaction with organized Jewish communities. For example, the letters never mention synagogues (contrary to Acts) and Wayne Meeks has argued emphatically that Pauline groups were organized independently of Jewish associations from the start, and thus were never really sects of Judaism. Of course, Nanos could have argued that because the Roman Christians were not the result of Paul’s mission work, his pattern of community formation is not relevant to interpreting the socialization of Christians in Rome. But, this is precisely what Nanos does not do! He sees the situation in Rome as typical of the Pauline mission.

Second, much of the force of Nanos’s argument rests on his reading of the infamous “weak” and “strong” passage (Romans 14:1–15:13). If the “weak” are in fact Jews who have not yet accepted Jesus as their Christ, Nanos has a compelling case. If not, he lacks evidence for his thesis. Nanos believes that readers have almost no choice but to accept his identification because otherwise they fall into “Luther’s trap:” If Paul forbids the “strong” to judge the “weak” in Romans 14:1, you 054cannot have Paul in the same text judging negatively the faith of a Christian as weak (that is, immature because of continuing to observe the Jewish Law).

Third, making the “authorities” of Romans 13:1–7 Jewish synagogue leaders rather than Roman administrators is intriguing. This reading does solve some of the problems scholars have encountered connecting the passage to the rest of Romans, but it has little else to commend it unless you accept beforehand Nanos’s thesis, namely, the socialization of Christians entirely within the synagogues. Even then, it is difficult to account for Paul referring to synagogue leaders as authorities who “do not bear the sword in vain.” Moreover, Nanos’s detailed description of the role of synagogue leaders and how they would have affected the Christians is based largely on late evidence (catacomb inscriptions from the third century or later) and on considerable speculation.

Fourth, in recent years scholars increasingly have considered the Claudian Edict—an order that evicted (some) Jews, possibly including Christians, from Rome in the 40s C.E.—to have been a Roman administrative action that exacerbated tensions between Jews and Christians in Rome. Nanos, however, plays down any such tensions and completely ignores the edict in his reading of the letter.

Finally, Nanos argues for overlap between Acts and Romans where many scholars have found contrast: The “Restoration of Israel” is pursued on the basis of a “divine two-step pattern” by both Luke and Paul, and the “Apostolic Decree” of Acts 15 is faithfully implemented by Paul in Romans 14. Interestingly, Nanos makes a strong case for not interpreting Romans in light of Paul’s other letters, but then spends an unusual amount of time interpreting Romans in light of Acts. His attraction to Acts is understandable. Nanos wants to do for modern readers what Luke sought to do for his readers: provide a more “Jewish” Paul.

As promised, Nanos has offered his readers a new lens to view Paul. Whether the Paul one sees through this lens is the Paul who wrote Romans is, however, another question. Because Nanos has developed a coherent alternative to common assumptions regarding Paul and has argued his case with rhetorical skill, he may encourage Pauline scholars to revisit the whole question of Paul’s “Jewishness” and its import for Paul’s theology and mission.

Torah as Therapy

Self, Struggle & Change: Family Conflict Stories in Genesis and Their Healing Insights for Our Lives

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.