Bible Books

010

Sex, Violence and Greed

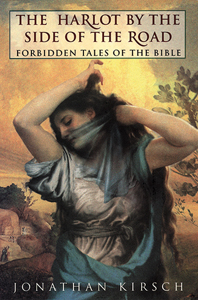

The Harlot by the Side of the Road: Forbidden Tales of the Bible

Jonathan Kirsch

(New York: Ballantine Books, 1997), 378 pp., $27.00 (hardback)

Many modern readers think of the Bible as a “dry and preachy” book, not having much sympathy for the all-too-human passions of sex, violence and greed. In this book, Jonathan Kirsch, author, book columnist for the Los Angeles Times and practicing lawyer, attempts to change that impression, to reveal the Bible’s fullness in recounting human complexity. In the process, Kirsch hopes “to take back the Bible from the strict and censorious people who wave it in our faces and to restore it to the worldly man or woman who will appreciate the flesh-and-blood passions that are described in the Holy Scriptures.”

Unlike most books about the Bible, this one begins with a warning: “The stories you are about to read are some of the most violent and sexually explicit in all of Western literature. They are tales of human passion in all of its infinite variety: adultery, seduction, incest, rape, mutilation, assassination, torture, sacrifice, and murder. And yet every one of these stories is drawn directly from the pages of the Holy Bible.”

“Hidden away in the odd cracks and corners of Holy Scriptures,” these stories have been overlooked because their contents are often shocking. Religious authorities, according to Kirsch, have smoothed over, euphemized away, and just plain ignored these stories, leaving most readers unaware of their existence.

Kirsch draws attention to the lesser-known accounts of Lot and his daughters (Genesis 19:1–38), the rape of Dinah (Genesis 34:1–31), Tamar and Judah (Genesis 38:1–26), Zipporah and Moses (Exodus 4:24–26), Jephthah and his daughter (Judges 11:1–40), the traveler and his concubine (Judges 19:1–30), and Tamar and Amnon (2 Samuel 13:1–22).

Kirsch treats each story in two or three chapters. The first chapter retells the story in modern English, expanded and embellished with details not found in the biblical text. As a check on his creativity, Kirsch includes the biblical story in boxes alongside his retold story. For this purpose, Kirsch uses the 1917 Jewish Publication Society translation—one of the few weaknesses of the book: This archaic translation will be difficult for the average reader to comprehend easily. Kirsch would have been better served by using a more modern translation, for example, the New Jewish Publication Society translation, published in 1985.

In his expansions and embellishments, Kirsch draws on extrabiblical retellings of the stories, such as rabbinic midrash, as well as his own imagination. For example, in the story of Jephthah and his daughter in Judges 19, the daughter is nameless. However, when Pseudo-Philo, a first-century C.E. Jewish author, retold the tale, he gave the daughter’s name as Seila, and Kirsch reuses this name in his version.

Following the retelling, Kirsch devotes a chapter to explaining the story and why it has been so difficult for believers to accept this tale as part of the Bible. Kirsch includes a very readable discussion of contemporary scholarship on the passage and then draws his own conclusions. For example, in the story of Zipporah and Moses (Exodus 4), the text seems to say that God attacked Moses on his way back to Egypt and attempted to kill him! Kirsch 012notes that Moses appears to be saved by Zipporah’s action when she circumcises her son and then smears the blood on somebody’s (God’s or Moses’) feet (or genitals). He attributes this story to an ancient tradition of the need to appease the deity by bloodletting. This may be uncomfortable for our contemporary theological notions (a God who demands human blood and threatens to kill his prophet would seem to contradict a portrait of God as all-loving and merciful), but it is based on sound scholarship. These chapters illustrate the thoroughness of Kirsch’s research in preparing this book, both through the endnotes and the extensive bibliography, which lead the interested reader to further research.

The Harlot by the Side of the Road would be an excellent addition to the library of the interested layperson or a valuable supplemental text in an undergraduate course. Jonathan Kirsch has produced a book that is a responsible treatment of some rather shocking and sensational biblical stories, and I recommend it to the readers of BR.

Families in the New Testament World: Households and House Churches

Carolyn Osiek and David L. Balch

The Family, Religion, and Culture series, ed. by Don S. Browning and Ian S. Evison

(Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1997) 329 pp., $25.00 (paperback)

“Family values” has recently become a catchword among traditional Jews and Christians, especially politicians. Many proponents cite the Bible in support of these values. Yet how much do we really know about family values in the biblical world?

The study of the social world of the ancient Near East began fairly recently. In the 1950s, social historians fused two fields that had been traditionally antagonistic: sociology-anthropology, which attempts to explain present-day human groups and their activities in general; and the historical sciences, which interpret past human beings and their activities in particular. Armed with basic social-scientific theory, Bible scholars soon followed suit. Working with archaeological remains and ancient literature, they began asking hard questions about ordinary, everyday life in biblical times.

More than two decades of research has produced a great deal of information about both the rich and the poor, males and females, husbands and wives, parents and children, masters and slaves, and the literate and illiterate in the ancient world. Now Carolyn Osiek of the Catholic Theological Union and David Balch of Texas Christian University have gathered the results of this research in one handy volume. Theirs is the first comprehensive synthesis and discussion of archaeological, classical, social-historical and cultural-anthropological research on houses, households and family life among ancient Greeks, Romans and Christians from the fourth century B.C.E. to the fifth century C.E.

To illustrate Osiek and Balch’s approach, let’s examine how they approach relationships between men and women.

014

The authors accept the cultural-anthropological generalization that human societies normally separate space according to gender and that, in more traditional societies, male space is public and political while female space is private and domestic. But they go beyond this level of generalization to examine specific regional and subgroup variations, looking at archaeological remains and ancient literature, and modern interpretations of them.

A modern example illustrates some of the kinds of information that may be discovered about a society from its homes. Today northern European and North American homes have doors (often locked) on the outside. These homes are designed to provide shelter in cold winters. This indicates that the residents place a premium on indoor living. While certain values about a woman’s place being in the home still linger, male space and female space are no longer rigidly separated. In contrast, ancient Mediterranean homes were designed with the rooms facing inward towards a central open courtyard, normally colonnaded (known as a peristyle), an enclosed space that allowed for much private yet outdoor living in a mild-to-hot climate. Generally, men and women were spatially segregated at home, in a way that indicates male dominance. For example, Greek homes, at least those belonging to the affluent, had rooms in the front in which the male head of the household received guests and did business; women’s quarters (gynaikonitis), used for domestic activities, were in the back.

Roman residences usually had an atrium in the front for receiving guests and doing business, which was used mostly by men, although men’s and women’s quarters were not as neatly separated as in Greek homes. The same was true later in the Greek East. Wealthier homes in Roman Palestine and Syria also had a central courtyard, generally without a peristyle; Osiek and Balch do not explicitly comment on male and female space in these homes.

The authors discuss other matters related to household space and social relations in the Greco-Roman world, for example, the lack of privacy and segregated slave quarters. However, since the early Christians met, worshiped and socialized in “house churches” with the same sort of floor plan as those described above, the central question is, How did the homes and families of this subgroup compare to those in the wider cultural environment?

The second part of the book (about two-thirds of it) deals with Christian beliefs, norms and values concerning social status, gender roles, marriage, celibacy, education, slavery, family life, meals and hospitality as reflected in the New Testament and other early Christian literature.

Again, their approach can be illustrated by their commentary on gender roles and male dominance. The authors describe commonly held cultural views on promoting sexual asceticism and denouncing male sexual promiscuity. They show how the Corinthian Christians held such views, claiming that “it is well for a man not to touch a woman” (1 Corinthians 7:1), and that Paul rejected such views as too extreme (1 Corinthians 7:2–6), transferring Stoic mutuality in friendship among men to mutuality in sexual obligations between men and women. Paul wrote, “The husband should give to his wife her conjugal rights, and likewise the wife to her husband. For the wife does not have authority over her own body, but the husband does; 015likewise the husband does not have authority over his own body, but the wife does” (1 Corinthians 7:3–4). The authors also show how Christianity after Paul became acculturated to the norm of male dominance, for example, in the traditional household codes: “Wives, be subject to your husbands as you are to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife just as Christ is head of the church” (Ephesians 5:22–23; see also Colossians 3:18–4:1; 1 Timothy 3, 5; Titus 1). In short, some early Christians like Paul were “countercultural” and others assimilated to the culture. With occasional attention to noncanonical books, the authors move from one New Testament text to another, attempting to indicate their relative degree of assimilation or lack thereof.

No book can do everything. This one focuses on the larger Greco-Roman world, which necessitates somewhat less attention to Judaism. On status questions, it accepts the “new consensus” among Pauline scholars about the importance of high-status leaders in the urban world of Paul, that is, in the Pauline letters and Acts, where the data are more explicit than in the gospels because Paul is directly expressing early Christian problems. Thus the authors give comparatively less space to rural peasant homes and families in the Palestinian world of Jesus described in the Synoptic Gospels, where the data are more implicit (for example, in the parables). They also tend to romanticize gender roles in the Gospel of Matthew, which, despite some other countercultural trends in this gospel, is in my view still predominantly patriarchal. On at least one occasion, the authors shift from social description of gender roles to theological and moral “outrage” over these roles, which, while understandable according to modern Western values, and while perhaps appropriate for the series, is nonetheless surprising for a social-historical work.

Yet these few limitations, mostly self-imposed, are minor in comparison with the book’s impressive achievement. No other work brings together such wide-ranging research on households and the family in the world of early Christianity. The study is timely, well written, well documented, and highly informed and informative. It will be very valuable for scholars and students of the social history of the New Testament and thus for courses in this area. It should be “required reading” for any person who wishes to know more about households, families and family values in both the world of the New Testament and in the New Testament itself.

Many scholars (unlike some politicians) claim that biblical values are remote from modern values; thus, they seek to distinguish what is permanently valid and what is “time-bound.” Osiek and Balch do not attempt to answer such theological and moral questions definitively. However, they do highlight some striking differences between ancient Mediterranean and modern Western values about home and family. Anyone who understands these differences will hardly appropriate New Testament values without serious reflection and interpretation.

Sex, Violence and Greed

The Harlot by the Side of the Road: Forbidden Tales of the Bible

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.