Bible Books

046

Snapshots of the Holy

Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America

Colleen McDannell

(New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 1995) 312 pp., $40.00 (hardback), $18.00 (paperback)

Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images

David Morgan

(Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1998) 265 pp., $35.00 (hardback)

American Christians “want to see, hear, and touch God” in ordinary, everyday situations, putting into question the boundary theologians have often insisted separates the “sacred” from the “profane.” Cardboard icons, plaques, plastic buttons, bumper stickers, T-shirts and other mass-produced images have come to feed—and are fed by—the devotional practices and environments of ordinary people. These works by Colleen McDannell and David Morgan are part of a recent movement to open religious studies to a serious examination and appreciation of this “material dimension,” or “visual culture” of religion. Focusing largely on Christianity in the United States, these scholars present some theoretical background and several case histories in their examination of “religious stuff.”

McDannell’s hefty volume, filled with illustrations in both black-and-white and color, is a good place to start. She discusses and illustrates the nature of religious relics, shrines, souvenirs, plaques, pictures, grave markers, toys and more as evidence of an overlooked dimension of religion, the material dimension. Might the Bible be viewed not only as a text to be interpreted, asks McDannell, but as an “artifact” whose very display in the home conveys a message, whose visual illustrations and material presence play a part in constructing our world and establishing our personal identity? McDannell, who holds the Sterling McMurrin Chair of Religious Studies at the University of Utah, provides a chapter on “The Bible in the Victorian Home,” a study of “The Religious Symbolism of Laurel Hill Cemetery” in Philadelphia, a study of the popularity of Lourdes water and of shrines among American Catholics, and a study of the meaning of Mormon “sacred” undergarments.

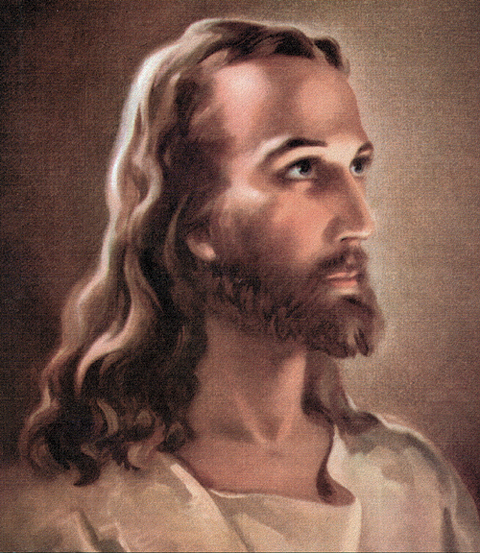

David Morgan’s Visual Piety is more difficult to assess. Morgan placed ads displaying a reproduction of Warner Sallman’s famous painting Head of Christ (at right) in about 20 religious periodicals and asked for readers’ responses regarding the meaning of that image to them. He received and analyzed 531 answers. Morgan here asks how it is that despite the Bible’s lack of any description of Jesus’ physical appearance, Sallman’s Head of Christ is instantly recognized by diverse groups of Christians.

On the one hand, one might accuse the author of squeezing a second book out of a piece of research that had already done its job in a first volume, Icons of American Protestantism: The Art of Warner Sallman (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 1996). Based on the same research project, the earlier book was Morgan’s first attempt to evaluate readers’ responses to his poll. Whether a second volume that continually refers to those same responses is warranted is questionable. One might have expected the incorporation of new studies dealing in depth with African American or Asian American responses, other seminal images, or the like.

On the other hand, Visual Piety does 047provide a fascinating discussion of the power and meaning of religious artifacts, largely paintings and drawings. Morgan is an art historian at Valparaiso University but is quite willing to engage thinkers beyond his field, including thinkers in sociology, theology, hermeneutics and philosophy. Morgan’s themes—the changing views of male friendship (David and Jonathan), the theological roles of empathy and sympathy, feminine and masculine aspects of the portrayal of Jesus, and avant-garde and popular imagery—are bound to stimulate new avenues of study in religion.

Both McDannell’s Material Christianity and Morgan’s Visual Piety provide stimulating reading and point us toward new concerns in religious studies, directions that suggest the need to take into account “image” with the same seriousness we have invested in “word.” The two volumes leave us wishing for greater structure to the discussions, but the lack of structure is perhaps to be expected when new territories in religious studies are being mapped.

Judith: Sexual Warrior

Women and Power in Western CultureMargarita Stocker

(New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 1998) 352 pp., $30.00 (hardback)

Bible criticism over the past century in some ways resembles X-ray technology: Scholars seek to understand what lies beneath the Bible’s skin—what stories from ancient Near Eastern tradition, say, might underlie the tales of Genesis or what fragments of Jesus’ actual words might still be embedded in the highly redacted and embellished gospel accounts.

More recently, however, some biblical scholars have developed a strong interest in the history of biblical interpretation, attempting to describe how the Bible has been understood by exegetes throughout its 2,000-year history. James Kugel, for one, has explored rabbinic, early Christian and Islamic interpretations of the Joseph story in his 1987 book In Potiphar’s House: The Interpretive Life of Biblical Texts, and Gary Anderson has examined early Jewish and Christian interpretations of the Garden of Eden story.

Margarita Stocker’s Judith: Sexual Warrior is in some ways a part of this more recent scholarly trend, as she explores the ways in which Judith, the heroine of the apocryphal book of the same name, has been understood by the Bible’s readers over the last 600 years. At the same time, Stocker’s work is markedly different than, say, Kugel’s or Anderson’s; she does not focus on how Judith has been understood by scholarly commentators such as the church fathers and the rabbis. Rather, she examines the ways Judith has been understood in the wider Western culture: in art, in poems, in novels, in political treatises and even in less exalted cultural forms, such as 16th-century German pottery, Flemish glass, English jewelry and movies.

The Book of Judith tells of a military campaign under the command of Holofernes, a general of the Babylonian ruler Nebuchadnezzar.a When Holofernes threatens the Israelites, Judith, a widow, adorns herself with her finest clothes, enters the enemy camp and beguiles the general with her beauty. After several days of feasting and drinking, Holofernes collapses in his tent at Judith’s feet. The heroine takes Holofernes’s sword and cuts off his head. The invading army, badly rattled by the loss of its leader, is defeated the next day by the Israelites and Judith is hailed as a hero.

Stocker compellingly demonstrates how widespread and varied the image of Judith has been in the history of Western civilization. She was seen as an emblem of the virtues of chastity, temperance, fortitude, wisdom and humility in the Middle Ages, yet as an erotic symbol and even a patron of courtesans in the Renaissance; as a political activist and paragon for the anti-authoritarian ideals of the French Revolution at the end of the 18th century, yet as a figure of unrestrained violence and of women’s murderous impulses in the minds of the 19th-century English Victorians. Stocker makes clear that Judith can represent many things even in the same historical moment: She describes in detail how, after the citizens of revolutionary France split into rival parties, Charlotte Corday, of the Girondin faction, could understand herself as taking a Judith-like stand against tyranny when she assassinated the radical journalist Marat in his bath. For their part, Marat’s allies, of the Montagnard faction, perceived him as the representative of the Revolution’s ideals of liberty and viewed Corday as a Judith-like deceiver and murderess who recklessly claimed the right to pursue justice as she saw fit.

Stocker’s ability to range so widely through time and various media, to tease out nuances as she explores the ever-changing imagery of Judith, makes this book an intellectual tour de force. Still, as is inevitable when one tries to do so much, there are problems. For example, 048Stocker seems so driven to find later cultural manifestations of the biblical Judith that she sometimes appears to force the identification: She identifies Judy, of the Punch and Judy puppet show, as a Judith figure, based on her claim that Punch’s dog, Toby, was named after the apocryphal Book of Tobit. This seems a stretch, even if the Toby-Tobit connection is true. And we can’t be sure that it is, since Stocker offers no documentation in support.

The frequent failure to footnote, in fact, is a problem throughout the book (nor is there a bibliography). Sometimes, the footnotes are there, but they are skimpy. As evidence for one of the facts crucial to her French Revolution argument—that Charlotte Corday understood herself as a Judith figure—Stocker cites only a 1935 biography of Corday and gives no specific page numbers. Elsewhere, footnotes direct the reader to unpublished (and hence unavailable) papers by Stocker. Such failures to document her case adequately often make it seem as if Stocker is simply asserting, rather than proving, a point. Thus, in a discussion of Jan de Bray’s painting of Judith, we read, “the snuffed candle on the table symbolizes…the phallus…the basin next to it encodes both vagina and womb.” Well, maybe—but maybe sometimes a candle is just a candle and a bowl is just a bowl.

American readers might find themselves bothered by the fact that Stocker, who is British, discusses relatively few manifestations of Judith in American culture: Indeed, the first reference to an American work I found was more than halfway through the book, even though the discussion of the period of history in which America emerged had begun almost 50 pages earlier. Jewish readers likewise may find themselves disconcerted by the overwhelmingly Christian focus of the book, as it is only in Stocker’s discussion of the modern State of Israel that she considers how Judith imagery is used in a Jewish context.

Stocker’s language at points is overladen with jargon: The made-up word “acteme,” for example, is used to describe Judith’s murder of Holofernes; the Renaissance images of Judith as a courtesan are called “Judithic” erotica; tyrannicide is described as “Judithically” feminine. This jargon, moreover, tends towards the rather specialized and—to the uninitiated—inaccessible language of postmodernism: “How could women represent the male subject’s transgressive alterity?” Stocker writes.

One other problem: While we owe a great debt of thanks to Yale University Press for undertaking the expense of reproducing 36 of the artistic images Stocker discusses—nine of them in gorgeous color—it is frustrating that there are no references within Stocker’s text that direct us to the relevant reproductions (which are all grouped together at two central points in the book). One suspects the editorial process is to blame here, since a parenthetical note referring to “fig. ?” occurs in Stocker’s discussion of one painting. This suggests that at some point Stocker and the publisher did intend to give the reader plate citations.

Readers of Stocker’s book will find themselves compelled at first by Stocker’s fascinating subject matter and by the enormous range of materials she considers. Ultimately, however, many will find themselves lost along the way, undone by the book’s spotty system of citation, its tendency to assert rather than prove and its Eurocentric, Christocentric and postmodern orientation.

Snapshots of the Holy

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

The Five Scrolls has been published in three editions: The congregational edition (reviewed here) includes both the translation of the five books and prayers to accompany the reading of the books in the synagogue on the holidays when it is traditional to do so; the next version, without prayers, in a larger format than the congregationnal ($60), and the special limited edition in large format printed on rag paper with a hand-pulled Baskin etching, signed and numbered by the artist ($675). In all three versions, Baskin’s 37 watercolor illustrations are included.