Biblical Profile: The Birth of Noah

In the spring of 1947, the first Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered. Among them was a scroll from Qumran Cave 1 that came to be known as the Genesis Apocryphon.1

As 1947 was the year preceding the founding of the State of Israel, these days were neither the most peaceful nor the best suited for archaeological expeditions. Because of the political and military turmoil, four of the first-found scrolls were transported from Jerusalem to Lebanon and further to Syria, before eventually arriving in the United States.

Three of the scrolls could be unrolled rather easily. The fourth scroll, however, was not only very difficult to unroll, but just before scholars would launch this delicate procedure, the then-owner of the scroll, the Metropolitan of St. Mark’s Monastery in the Old City of Jerusalem, withdrew his permission to have it unrolled. His motivation was apparently more financial than scholarly, as he expected that the scroll’s monetary value would be greater in its unrolled state. Obviously, the Metropolitan’s deliberations are understandable in view of the dire circumstances of many of his parishioners at those times.

Only after these scrolls were purchased by the emerging State of Israel for the sum of 250,000 USD could this fourth scroll be opened.

During the reconstruction process, it was found that the fourth scroll contained stories, written in Aramaic, about the patriarchs known from the biblical Book of Genesis. The scroll enhances the biblical narratives with interesting details. Since the first parts of the book have been lost, the reconstructed text begins with the story of Lamech, the father of Noah, and ends right after the story of Abraham freeing the captives of Sodom taken prisoner in the military campaign of the “kings of the east.” As such, the extant part loosely covers the biblical narrative from the end of Genesis 5 through the beginning of Genesis 15.2

Radiocarbon dating indicates that the document originated between 73 B.C.E. and 14 C.E. The content of the book shows familiarity with the tradition found in the Book of Enoch (written between 300 and 100 B.C.E.) and the Book of Jubilees (written c. 160 B.C.E.), both examples of expanded biblical narratives.

The Genesis Apocryphon has most of its personages speaking in direct speech. Fascinatingly, we not only hear the main biblical characters speaking, but also marginal ones, and even some completely absent from Genesis. These added dialogues and details do more than merely satisfy the reader’s curiosity. The author retells the Genesis story in such a way as to explain what could have been seen as flaws of the biblical patriarchs.

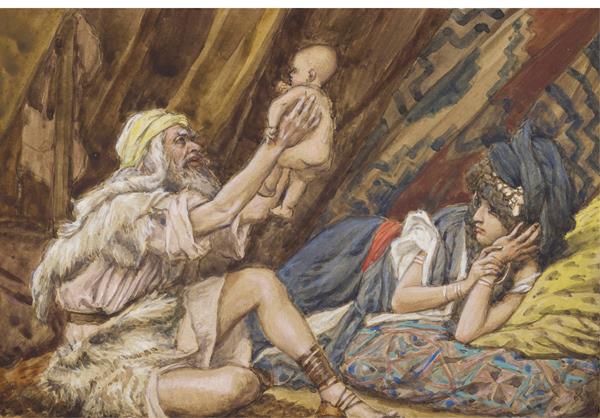

One example of such an expansion of the biblical Genesis involves Lamech, the father of Noah. When Lamech sees his newborn son, he concludes that he hardly can be the father of this child. He thinks that one of the “Watchers,” the “Holy Ones,” or the “Nephilim”—in short, the fallen angels—must have fathered the child.3 This is obviously a reference to the narrative of Genesis 6:1-4, about the “sons of God” who had children with the “daughters of men.”a

But why is Lamech so distrustful? After all, would it really occur to any reader of Genesis that Noah could have been born from a relationship between heavenly or semi-heavenly beings and a human mother? Yet the tradition preserved in the Book of Enoch relates how Noah right after his birth was able to speak and that his eyes were like sunrays, lighting up the whole house.4 So far, we see only a slight, suggestive Enochic embellishment. But then the author provides an elaborately detailed defense of Bitenosh, Lamech’s wife, who assures her husband that he really is the father of Noah. In a graphic retelling of the encounter, Bitenosh reminds Lamech of their sexual intercourse that resulted in the conception of their child (1QapGen 2:8–18).

The whole dialogue between Lamech and Bitenosh about the conception of Noah is a new exegetical addition, found neither in Enoch nor in Jubilees. But why? The answer may simply be hidden in the name of Noah’s mother. Within the Second Temple traditions, and also in the Genesis Apocryphon, she is called Bitenosh.5 Her name means “daughter of man,” something that for Aramaic-speaking readers immediately would have functioned as an allusion to Genesis 6:1-4, where the “daughters of men” enter into relationships with the “sons of God.” This may be the reason that the author of the Genesis Apocryphon adds this dialogue between Noah’s parents. There can be no misunderstanding in the Genesis Apocryphon: Bitenosh, Noah’s mother, was obviously not one of those “daughters of men” mentioned in Genesis 6:1-4.

In contrast, the biblical narrative itself does not seem to care that much about the reputation of its characters, disclosing even their flaws. And, perhaps, readers who live by the guidance of these ancient texts may learn even more from the flaws of biblical characters than from their strengths.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. See Jaap Doedens, Biblical Profile: “Exploring the Story of the Sons of God,” BAR, Summer 2020.

Endnotes

1.

Numbered 1Q20 or 1QapGen. For text and English translation, see Florentino García Martínez and Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar, eds., The Dead Sea Scrolls: Study Edition, vol. 1 (Leiden: Brill, 2005), pp. 26–49. See also Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Genesis Apocryphon of Qumran Cave 1 (1Q20): A Commentary, BibOr, 18/B (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 2004); Daniel A. Machiela, The Dead Sea Genesis Apocryphon: A New Text and Translation with Introduction and Special Treatment of Columns 13–17, STDJ 79 (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

2.

Based on vague traces of numbering of the columns, the scroll must have been much longer, probably missing between 70 and 105 columns. See Fitzmyer, Genesis Apocryphon, p. 38.

3. 1QapGen 2:1 mentions the “Watchers” (Aramaic: עירין) and “Holy Ones” (Aramaic: קדישין). These are the standard designations within the Dead Sea Scrolls for those who are called the “sons of God” in Genesis 6:1–4. The Nephilim (Hebrew: נפלים; Aramaic: נפילין) are most probably to be seen as the offspring of the “sons of God” (Hebrew: בני־האלהים) and the “daughters of men” (Hebrew: האדם בנות).