Dining with the Divine

Anyone and everyone could pray to a god in ancient times, but often only family members could join him for meals.

014

Divinity, in antiquity, was local. It attached to places. However gods were imagined, whatever their relation to the upper cosmos, they lived in human society, too. Groves, grottos, mountaintops and springs: Nature provided earthly homes for the divine. Gods, of course, were also urban creatures. Cities held shrines. In Olympus, Delos and Jerusalem, on earth as in heaven, gods dwelled in particular locales, even in particular buildings. The Gospel of Matthew makes this point nicely. “He who swears by the Temple,” Jesus taught, “swears by it and by Him who dwells in it” (Matthew 23:21).

Most specifically, in city and country, gods lived around their altars. This was true of the gods of the Greeks as well as the god of the Jews. Altars were hot zones of divine-human interaction. Of course, encounters with the divinity could and did occur by chance: most commonly, in dreams; but also in sudden epiphanies, visual, aural or even olfactory (the “odor of sanctity” was a dead giveaway of divine presence); and in plagues or earthquakes or floods (usually interpreted as manifestations of divine anger). But altars were the focus of scripted encounters. Around altars, gods and men enacted a fundamental binding social ritual: They ate together. The blood and flesh of offerings provided the medium of this encounter, cautiously governed by purity rules. These rules—which usually had been revealed by the god himself—guaranteed that the human was in the correct state to approach the divine. Mistakes made gods angry; proper ritual and piety, the indices of respect, affection and loyalty, pleased them and disposed them to be gracious. In such engagements, human scrupulousness paid off.

But divinity was local in a second sense, too. In antiquity, religion ran in the blood: Ethnicity expressed religion, and religious practice expressed ethnicity. Myths of primordial breedings between a god and a mortal might account for this connection between heaven and a people or its ruler. Aeneas was related directly to Venus—a connection that centuries later benefited his descendant, Julius Caesar. Alexander the Great, “fathered” by Zeus, was himself isa theou, “also divine.” People or rulers might be adopted by heavenly patrons. Abraham and his family, according to biblical tradition called by the creator, became the people of Israel; this people’s king was their god’s “son.” In 2 Samuel 7:14, God says of Solomon: “I will 062be a father to him and he shall be my son” (see also Psalm 2:7). The adoption might extend to the entire people, who then also became the god’s “sons.” In Exodus 4:22, God describes all Israel as his “first-born son” (see also Romans 9:4). In short: Gods and their worship passed from one generation to the next within the extended family of a people. Cult was a kinship designation.

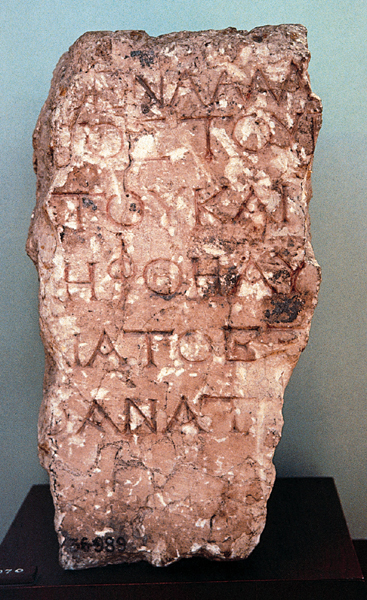

This is the cultural context for two inscriptions from antiquity. Each demarcates the boundary of a sanctuary. The first reads: “It is not lawful for a xenos [foreigner, stranger] to enter.” The second states: “No man of another nation to enter within the fence and enclosure around the temple.”

Both inscriptions come from sites of major religious and civic/political importance to their peoples. However, both sites also attracted huge numbers of foreigners to the shrines of their respective gods. As the two inscriptions make clear, in neither place was a foreigner permitted proximity to the god’s altar: That was the privilege and duty of the god’s people. But visitors were encouraged to worship and to show their respect in other ways. In Delos, home to the first inscription, a special sacrificial officer called the proxenos (the title means “for the stranger”) closed the liturgical gap between non-Delians and the god Apollo, who was worshiped there. In Jerusalem, home to the second inscription, the largest court ringing the sanctuary of the Temple compound was given over to “the nations”: In this court, Gentiles could worship the god of Israel, just not directly at his altar.

The Gospels depict Jesus dramatically disrupting the support services housed in this Court of the Gentiles. He turns over the tables of the moneychangers and pigeon sellers whose stations ringed the court. In relating this scene, Mark and, following him, Matthew, attribute to Jesus a quotation from Isaiah: “Is it not written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer for all the nations?’” (Mark 11:17//Matthew 21:13). This verse, and indeed Jesus’ action, have been interpreted in later Christian tradition as a condemnation of the sacrifices at the Temple. In this view, the offerings and sacrifices occurring there (facilitated by the moneychangers and the pigeon sellers) impeded prayer, the “true” function of the Temple. By disrupting such transactions, Jesus “cleansed” the Temple, which is the traditional title given to this scene.a

However useful such an interpretation might be for later Christian theology, it completely confuses first-century Jewish history. In Jesus’ lifetime as for generations before and for one more generation after, the Temple already was “a house of prayer for all the nations.” At the same time, without mixture or confusion, it was the house of sacrifice for Israel. If Jesus had condemned such sacrifices, his apostle Paul was unaware: He names latreia (“altar sacrifice,” Hebrew avadoah, translated bloodlessly in the RSV as “worship”), along with the people’s “sonship” as two of God’s privileges to his genos (nation, people), Israel (Romans 9:4–5).

In sum, prayer and sacrifice did not compete as modes of religiousness. Everyone could pray, and when at a god’s sanctuary, everyone should pray. But sacrifice, in Jerusalem as at Delos as at countless cult sites throughout the Mediterranean, was often just for the genos. In antiquity, when gods and humans got together, eating was frequently a family affair.

Divinity, in antiquity, was local. It attached to places. However gods were imagined, whatever their relation to the upper cosmos, they lived in human society, too. Groves, grottos, mountaintops and springs: Nature provided earthly homes for the divine. Gods, of course, were also urban creatures. Cities held shrines. In Olympus, Delos and Jerusalem, on earth as in heaven, gods dwelled in particular locales, even in particular buildings. The Gospel of Matthew makes this point nicely. “He who swears by the Temple,” Jesus taught, “swears by it and by Him who dwells in it” (Matthew 23:21). Most specifically, in city […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.