Expeditions

056

Banias: The Fountain of the Jordan

We were recently devising an itinerary for 44 people—most of them young—traveling to Israel. They felt they simply had to see all the sites associated with the Bible—which meant a lot of ruins! We knew we’d need some relief from the heat and the glare of sun on stone. We wondered, was there a site where we could combine the thrill of Biblical archaeology with some cool shade and the sound of running water? Where, in the words of the Scottish Bible scholar George Adam Smith, whose Historical Geography of the Holy Land (1894) we still treasure, could we give them “a vision of the Land as a whole” and help them “hear through it the sound of living history”?

Then we remembered Banias, located at the foot of Mt. Hermon, in the northernmost reaches of Israel. On our last trip to Israel, a visit to this site with our children revived both our spirits and theirs. Here, you may follow the Hermon River as it gushes forth from the rock, pause to explore the ancient remains it flows past and continue on with the roar of water in your ears as it tumbles down a gorge to what is almost certainly the biggest waterfall in the country. This easy, hour-long hike along one of the sources of the Jordan provides the perfect antidote to archaeology fatigue.

Mt. Hermon, with its three peaks, is the highest mountain (at 9,230 feet) in the Middle East, and it is never without its snowfields, even in midsummer. The mountain absorbs water like a giant sponge, only to discharge it into springs at its foothills. The three main headstreams, which unite to form the Jordan, are the Nahal Snir (in Arabic, Wadi Hatzbani), Nahal Dan and Nahal Hermon (Wadi Banias). Nahal Snir is the longest of the three, its spring being on the western or Lebanese side of the mountain, a popular picnic site for the local inhabitants. Dan has the most powerful spring, which gushes forth at the foot of Tel Dan, a site well documented in the pages of BAR.a But Nahal Hermon, the most easterly source, is located in the country’s loveliest valley, so enchanting that it was dubbed the “Syrian Tivoli” by Dean Stanley in the 19th century.

The Israelis captured the area from the Syrians during the Six-Day War in 1967. Pathways have since been cleared around the “fountain of the Jordan,” as it used to be called and the place has been declared a nature reserve.

The Walk

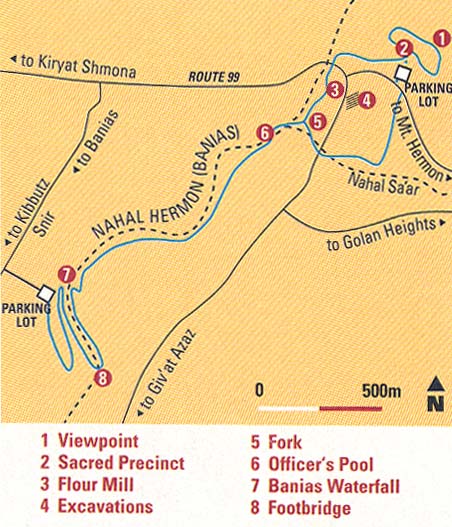

Leave the parking lot and before you get to the cultic site, take the path up to the left to get to a viewpoint (no. 1 on the plan) on the crest of the cliff where you can orient yourself. The Golan lies to the east, on your left, and the stately Mt. Hermon, on whose lower slopes you are standing, rises behind you. The Huleh Valley lies below you to the south, where the hills of Naphtali are also visible on your right. The excavations of the ancient palace of Banias, which you will visit later, lie across the road on the other side of the parking lot. To the right of the parking lot is a turret of a mosque, witness to the 1,300 years of Muslim rule (apart from short periods) of this place. On your right, on a ledge halfway down the cliff, is the wely (a tomb of a holy man) of el-Khader (a prophet who is sometimes associated with Elijah and sometimes with St. George). This site is holy to Muslims and also to the Druse, a breakaway sect of Islam based in the mountains of northern Israel, Lebanon and Syria. Beneath this little white-domed building lie the excavations of a Hellenistic-Roman cult site dedicated to Pan, the god of nature, trees and water. The name of Banias was 057derived from the Greek Paneas, meaning “holy to Pan.” This name has, as George A. Smith quaintly puts it, “survived to the present, only that Arabs, with no “p” upon their lips, spell it Banias.”

The ancient writers suggest that the cult place was built by the Ptolemaic kings in the third century B.C. in order to compete with the ancient Semitic cult place at nearby Dan. The Greek historian Polybius tells us that the Seleucids of Syria defeated the Egyptian Ptolemies here in about 200 B.C. and took control of the country. Retrace your steps down to the terrace at the foot of the cliff, where the sacred precinct (no. 2) dedicated to Pan is located. Moving along the terrace from left to right (west to east), you first encounter the grotto from which the source of the Jordan originally emerged. (Earthquake activity has since shifted the source so that it now emerges from a crack below the grotto.) This is a large cave in front of which Herod the Great (37–4 B.C.) built a temple to his patron, the Roman emperor Augustus. Josephus described this white marble temple in War 1.404 and Antiquities 15.363, and an excavation team led by Zvi Ma’oz found two parallel walls that formed part of this temple. Look for the foundations of these walls running perpendicular to the cliff.

Because the cave is associated with pagan rites, Christian visitors often point to it as the origin of the term “Gates of Hell” used by Jesus during his visit to the site. Here the apostle Peter, when pressed, is said to have made his famous confession, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the Living God (Matthew 16:16), and Jesus responded, “Upon this rock will I build my church; and the gates of Hell shall not prevail against it” (Matthew 16:18).

Immediately to the east (right) of the cave, is a small rock-cut grotto surrounded by niches, which once held cult statues. This was the back wall of an open-air shrine known as the Court of Pan and the Nymphs. It was constructed in the first century A.D., after Herod the Great’s son, Herod Philip, built a pagan city on this site. He named it Caesarea in honor of Augustus Caesar, and it was called Caesarea Philippi to differentiate it from Caesarea Maritima, on the Mediterranean coast.

You have not yet exhausted the site’s riches, as remains of another temple lie just to the east. This is the Temple of Zeus, which the excavators believe was built on the 100th anniversary of the founding of the city by Philip. Along the east side of this temple is a semicircular courtyard facing a large rock niche. An inscription above the niche links this open-air shrine with Nemesis, goddess of justice and revenge.

At the end of the terrace, you can distinguish the remains of a primitive building, which was divided into three halls. This has been dubbed the Temple Tomb of the Goats from the abundance of animal bones, mainly sheep and goat, found here in rectangular-shaped niches. This is a vivid reminder of the sacred goats associated with the cult of Pan, half man, half goat, and the cult’s Dionysiac practices.

To get to the other area of excavations, follow the path from the pool just below the terrace and cross the river via a pedestrian bridge. Soon, on your right, you will pass a water-powered flour mill (no. 3). Of the hundreds of watermills used in the Holy Land in the early 19th century, this is the only one that is still run commercially today. The fragrant odor of baking from the little pita bakery brings back fleeting, nostalgic memories—an example of George Adam Smith’s “living history”!

Cross the road to visit the sumptuous remains of a first-century A.D. Roman city, excavated by Vassilios Tzaferis.b These excavations (no. 4) have uncovered a luxurious palace, with marble still attached to the walls in places. The presence of marble links the palace with Agrippa II (the great-grandson of Herod the Great), as an inscription found in Beirut records his practice of building with marble. This was the Agrippa who heard Paul give his defense plea in Caesarea Maritima (Acts 26) and who made this inland Caesarea his capital for almost half a century (c. 53–93 A.D.). Notable features to look for are the large basilica, or hall, which would have been used for court hearings, the huge round towers that fortified the palace and 058the colonnaded street that bisected the city, running from north to south. Remains of the public bathhouse, built into the palace after the death of Agrippa, are clearly visible in the excavations. You also cannot fail to notice the nearby medieval fortress, with its impressive gate tower.

When you have had your fill of ruins, leave the excavations along a path that follows the Nahal Hermon. At once, you have entered another dimension of woods and water. Cultivated trees—walnut and pomegranate—grow abundantly alongside native willows and plane trees. The melting waters of the Hermon snows dash across huge rocks of shiny limestone. After a short distance alongside the river you come to a fork (no. 5) in the path. Keep to the right, which will soon lead you out of the shade, where the sparkling river rushes to the plain. After a few minutes, this path will lead you past a large, concrete water-filled basin, called the “Officer’s Pool” (no. 6), which was built near a spring by Syrian officers stationed here before the Six-Day War. They apparently chose the spring because the water here is 10 degrees (F) warmer than the waters of Banias. You will also pass by additional flour mills, now forsaken. This is also a good area to spot coneys, the wild rabbit-like creatures that the Book of Proverbs tells us “make their houses in the rocks” (Proverbs 30:26).

The path then leads down to the magnificent Banias waterfall (no. 7), known in Hebrew as Mapal Snir. Continue walking until you can cross the river over a narrow footbridge (no. 8), then go back along the stepped path that leads down to the base of the roaring waterfall. The river descends here with a force unequaled by any waterfall in the rest of the country. Two white cascades fall on either side of an ancient plane tree.

The physical background to Psalm 42 can only be this waterfall: “O my God, my soul is cast down within me: therefore will I remember thee from the land of Jordan and the Hermonites, from the hill Mizar. Deep calleth unto deep at the noise of thy waterspouts, all thy waves and thy billows are gone over me.” Once you associate these words with this place, you will never read them again without the thunder of the water resounding in your ears.

A short walk brings you to the parking lot beside Kibbutz Snir. Ask your coach or a friend to pick you up here, or simply retrace your steps along the path back to the parking lot at Banias.

Travel Essentials

Getting to Banias takes about half an hour along a good road (Route 99) from Kiryat Shmona. Pass by the sign that reads “Banyas waterfall” and take the turn marked “Banyas,” some 3 miles farther on. Banias (Tel: 011–972-6–6902577) is one of 57 sites you can visit on a National Park ticket, which you can purchase at the unbelievably low price of 102 Israeli shekels (approximately $26).

Food and Drink

Nothing could be more delicious than a well-prepared picnic eaten beside rushing water. You can buy fresh pitas at the little bakery and fill them with hummus, cold meats, salads or whatever you fancy. If, however, you have not had time to prepare an open-air feast, there is a restaurant, which also serves cafeteria-style meals beside the falls.

Accommodations

A good place to stay is the Karei Deshe Youth Hostel on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. This is a thoroughly modern hostel whose architecture is inspired by ancient caravanserais. It has its own private beach and offers an excellent value. Tel: 011–972-6–6720601. The closest accommodations to Banias are the nearby Kibbutz Snir Guesthouse, Tel: 011–972-6–6952518 and the Hermon Field School, Tel: 011–972-6951523.

Kibbutz hotels in the area are: Hagoshrim Kibbutz Hotel—Tel: 011–972-6–6816000; Kfar Giladi Kibbutz Hotel—Tel: 011–972-6–6900000; and Kfar Blum Kibbutz Hotel—Tel: 011–972-6–6836611.

Banias: The Fountain of the Jordan We were recently devising an itinerary for 44 people—most of them young—traveling to Israel. They felt they simply had to see all the sites associated with the Bible—which meant a lot of ruins! We knew we’d need some relief from the heat and the glare of sun on stone. We wondered, was there a site where we could combine the thrill of Biblical archaeology with some cool shade and the sound of running water? Where, in the words of the Scottish Bible scholar George Adam Smith, whose Historical Geography of the Holy Land […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

See André Lemaire, “‘House of David’ Restored in Moabite Inscription,” BAR 20:03.

See John F. Wilson and Vassilios Tzaferis, “Banias Dig Reveals King’s Palace,” BAR 24:01.