Jerusalem’s Ethiopian Compound

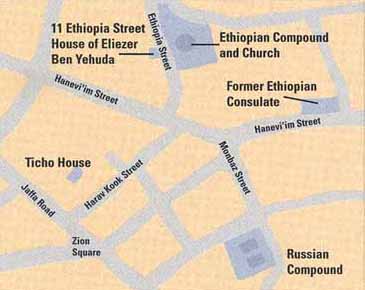

Jerusalem contains a seemingly endless number of fascinating, intimate neighborhoods, many of them little known except to lifelong residents. In a previous issue of BAR, we guided readers on a tour of Jerusalem’s Russian Compound.a Just north of that district is another island in this city where you are transported back to Biblical times and ways—the Ethiopian Compound.

Start your journey into Ethiopian Jerusalem on Hanevi’im Street, or the Street of the Prophets. By itself, a tour of this back road from Damascus Gate would be replete with interest: At the end of the last century it was the center of European activity, with hospitals, religious and educational institutions, consulates and private residences lining its route. These buildings, although not all equally well preserved, have retained their 19th-century form. Apart from the horrendous car traffic, you could easily be back in that cosmopolitan era again.

Intersecting Hanevi’im Street on the north is Rehov Hahabashim—Abyssinia (Ethiopia) Street. Some regard this as the most attractive little street in town, but it is one that Israelis, not tourists, frequent. High stone walls enclose two- and three-story buildings with tiled roofs and courtyards jeweled with flowers. Many of the houses on the eastern side were built by the Arab Nashashibi family for rental at the end of the last century.

At number 10, along this narrow street’s east side, is the gate into the Ethiopian Monastery. On both sides of its lintel, the Lion of Judah flanks an inscription in Ge’ez, the ancient liturgical language of the Ethiopians. It reads “Descendant of the Lion of Judah, Menelik the Second, King of Kings, Emperor of Ethiopia.” The Lion of Judah is the heraldic symbol of the Ethiopian royal house and is said to have been given by Solomon to the Queen of Sheba on her visit to Jerusalem. (Ethiopians believe “Sheba” to be Ethiopia) This gateway leads into a world that enchants all who enter. We lived here with our young family in the 1980s and never thought we would leave.

The Ethiopian monastery of Dabra Gannat (The Monastery of Paradise) was built between 1882 and 1893. It consists of a round church, which stands in a courtyard surrounded by monks’ quarters, a dining room, a bell tower and houses for rental to provide the monks with income.

The story behind this complex has echoes of the Biblical Nehemiah pleading for King Artaxerxes’ commission to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem after the Babylonian destruction. A book that the monks presented to us, called “Know Jerusalem” and written in 1962 by the then Ethiopian Archbishop, Abuna Philippos, reverentially tells the story of Memhir Wolde Samait, a former hermit monk in Jerusalem who had been elected to lead the Ethiopian Monastic Society in the city. As a leader of this society, Samait gained influence with the emperor of Ethiopia, Atse Johannes IV. Samait recounted to the emperor the misery of the monks in Jerusalem who, “besides not knowing the language of the country, lived in extreme poverty by depending on alms and begging from the communities around them during harvest-time.” Samait’s pleading had a similar effect to that of Nehemiah: Atse Yohannes dispatched 31 boxes of gold to the poor monasteries of Jerusalem. This enabled the Ethiopians to purchase a large plot of land and, in 1882, to commence building the church, along with a number of houses for rental. The next emperor, Atse Menelik II, took over the work of building the monastery, and the church was completed in 1893, hence the lintel at the entrance bearing his name. “Know Jerusalem” also describes a gallery of “distinguished ladies” who built houses for rental in the immediate vicinity and donated them to the monastery.

It doesn’t take long to explore the courtyard, but very quickly you leave the noise of the city behind. A visit to the church is worthwhile if it’s open; one of the monks can usually be prevailed upon to let you in. Its black dome, surmounted by the Ethiopian cross, stands out in aerial photographs but is less noticeable from immediately nearby. Inside the church two passageways laden with icons encircle the central “holy of holies.” The church’s round design is meant to deny Satan any corners to hide in. The congregation that gathers here on feast days like Easter—when the ranks of Jerusalem’s Ethiopian residents are swelled by an influx of pilgrims from Ethiopia, all swathed in white—is an enchanting sight.

However, the overwhelming impression we had while living in the Ethiopian compound was that the community that worships here has preserved Jewish customs from Bible times that are not found elsewhere in the Christian world. The names they give their children (Abraham, Solomon, Samuel, Gabriel and Michael were among the names of our children’s playmates) are the least of it: They also practise circumcision of males after eight days. When I gave birth to one of our sons while living here, I was fussed over and told to put my feet up for forty days—a bit unrealistic in my circumstances—but the advice was firmly based on the laws of purification after birth enumerated in Leviticus 12. We also knew a number of monks who had become eunuchs in response to the verses in Isaiah 56:3–5: “Unto them will I give in mine house and within my walls a place and a name better than of sons and of daughters.” Also, they observe the Sabbath on Saturday as well as on Sunday.

But perhaps the single most distinctive trait of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is the belief that the Ark of the Covenant was transported to Ethiopia by Menelik I, son of Solomon and Sheba. All Ethiopian churches have a replica of the Ark at their heart, inside a Holy of Holies. It is reputed that in the 1896 Battle of Adowa, the Ethiopian army under Menelik II (the same emperor who completed this monastery) carried a tabot (sacred replica) of the Ark, in the tradition of Joshua at Jericho. This battle against Italian invaders remains famous today as the first victory of an African nation over a colonial power. Indeed, the fervent dancing that we frequently observed in Ethiopian ritual makes us think of David dancing before the Ark.

Between the church and the balconied houses for rent behind it is a grove of lemon trees. For our family, the smell of citrus blossom in spring is now sufficient to stoke the embers of our memories of this place. Hopefully you will meet one of the black-robed monks who live in simple quarters around the monastery. Our favorite was Abba Abraham, who was never without a beaming smile and a sugar lump for our children in lieu of candy—he brushed away our worries of tooth decay with a wave of the hand.

Very few visitors are likely to speak Amharic, but the monks do speak some Hebrew, although very little English. Ask a monk to show you their Beit Lechem, the free-standing little stone house to the right of the church, in which they prepare the bread used in their Communion Service. The corners and doorways of this hidden courtyard captivate artists, who can often be seen painting a scene that has caught their fancy.

Leaving this oasis under the lintel of the Lion of Judah and stepping back into modern Jerusalem, look across the street at number 11 Ethiopia Street. Although there is no longer a plaque to commemorate him, this was once the home of Eliezer Ben Yehuda, the father of modern Hebrew. It is said that when he moved his wife and family here, his children were delighted by its colored glass windows. The house became the focal point in the war of languages when, just before the outbreak of World War I, Hebrew was in danger of being replaced by German in the country’s schools. Thinking Hebrew should be reserved for prayer and study, the ultra-Orthodox of the nearby Mea Shearim neighborhood still resent Ben Yehuda for reviving it as a language for modern secular Israelis, and have torn off the plaque so many times that the municipality no longer bothers to replace it.

Ethiopia Street is now a stimulating place to live (although the nearby areas have experienced terrorist attacks in recent years). Its residents include diplomats, journalists, writers, translators and artists. In Ben Yehuda’s time however, there must have been an extraordinary meeting of minds. In the book Tongue of the Prophets, a biography of Ben Yehuda by Robert St. John, Hemda Ben Yehuda, Eliezer’s second wife, is recorded as popping across the street to the American School of Oriental Research to confer with Professor Richard James Horatio Gottlieb, the head of the school from 1909 to 1910. She wanted his advice about raising money to finance the third volume of her husband’s dictionary. And in number 5, from 1902–1914, lived Professor Gustav Dalman, director of the German Archaeological Institute in Jerusalem, who wrote so eloquently about the land and specialised in Aramaic. One can only imagine the conversations.

Another corner of Ethiopian life lies hidden nearby. You can find this by retracing your steps along Ethiopia Street and turning east into Hanevi’im Street. A couple of hundred yards down on the north side is a large building whose gable is decorated with a mosaic of a lion on a blue background. This is the former Ethiopian Consulate, built between 1925 and 1928. In contrast to the monastery, this building is home to many of the community’s secular residents, ordinary Ethiopian families who choose to live in Israel. Climb the steps and cross over a dark hall into a large, tiled courtyard. If it’s not school hours, you’ll probably see children playing between the washing lines.

When we lived here for a year (before we moved to Ethiopia Street), we were shown inside the apartment where Emperor Haile Selassie, whom some Ethiopians believe to be the 225th direct line descendant of the son of Solomon and Sheba, lived during his exile in Jerusalem following the Italian invasion of his country in 1935. It’s the apartment with the balcony fronting onto Hanevi’im Street directly underneath the mosaic. This association with the figure Rastafarians worship as their Messiah is just another of the many fascinating links to the past that one encounters when exploring corners of this inescapably captivating city.

Travel Essentials

Food and drink

There is nowhere to dine on Ethiopia Street itself, but another of Jerusalem’s hidden courtyards, just across Hanevi’im Street, offers the promise of some physical refreshment. Walk down Harav Kook Street, just opposite the turn onto Ethiopia Street, to the Ticho House Café (Tel: 02–244186). Here snacks are served on a terrace overlooking a tranquil garden.

Find out about two of the city’s inspiring Jewish residents in the adjacent Ticho House Museum. Abraham Ticho was a Viennese eye doctor who ran an eye clinic in this house from 1924 to 1960. His patients came from all spheres of society. His wife, Anna, was a painter whose Jerusalem landscapes and portraits are in museums all over the world. You can catch a glimpse of their charmed life in the upper story of their home, which retains many of their personal effects. A selection of Anna Ticho’s paintings are exhibited on the ground floor of the museum.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See André Lemaire, “‘House of David’ Restored in Moabite Inscription,” BAR 20:03.