Field Notes

012

Built to Last

When the earth shook, ancient Turkish and Greek monuments stood their ground

The ultimate (or penultimate) year of the second millennium A.D., 1999, was a sorrowful one in Turkey and Greece. More than 17,000 people died in the earthquake that struck southeast of Istanbul on August 17. In September and November, thousands of people were killed or left homeless by powerful tremors that ripped through the Greek province of Attica.

Until recently, these Mediterranean nations focused their energies on serious, immediate problems: searching for survivors, caring for the injured, sheltering the homeless. Now the governments of Turkey and Greece are assessing the loss of their cultural heritage. The Greek Ministry of Culture reports that a number of museums and historical sites were damaged in the quake that hit Athens on September 7. The fourth-century B.C. fortress at Phyle and the sixth-century A.D. Church of St. Nicholas in Daphni both suffered major damage and will require extensive renovations before they reopen. The National 013Archaeological Museum in Athens was also forced to close for three days while curators repaired exhibits in the classical pottery collection.

In Turkey, sections of Istanbul’s ancient city wall collapsed, and the famous Mihrimah Sultan Mosque (erected in 1547 A.D. in honor of the daughter of the Ottoman sultan Sulaiman the Magnificent) developed deep fissures in its walls and foundations. It is unlikely the mosque will survive another serious quake.

Nevertheless, archaeologists and civil engineers emphasize that the real story involves not what fell down, but what stayed up. Most of Athens’s classical monuments—including the Acropolis—came through the tremors unscathed. In Istanbul, although scores of apartment buildings and commercial structures collapsed, not a single major Byzantine monument was seriously damaged.

Shock waves approaching 5.0 on the Richter scale rumbled through Hagia Sophia (above) on August 17, but the magnificent sixth-century A.D. basilica (once a church, then a mosque, and now a museum) lost nothing more than flecks of paint and chunks of 20th-century plaster.

According to Ahmet Cakmak, a professor of civil engineering at Princeton University, the great durability of Hagia Sophia and other Byzantine buildings reflects the long-term thinking of their architects. “These were people who wanted their buildings to last forever,” Cakmak told Archaeology Odyssey. “They understood earthquakes, [so they] built on bedrock, and they tried to build everything light.” Hagia Sophia, for example, is constructed of extremely shock-resistant, low-density brick and mortar. More than 1,400 years old, the basilica remains one of the world’s largest domed buildings.

Computer models designed by Cakmak suggest that it would take a severe quake—one striking right in the heart of Istanbul and measuring at least 7.5 on the Richter scale—to badly damage the celebrated edifice.

But this good news is just preliminary, cautions Cakmak. “All the equipment is out in the country saving people’s houses.” It’s still too soon, he said, to make a full accounting of the damage to monuments or to begin restorations.

012

Nero’s Folly

Built on Rome’s ashes, imitated during the Renaissance, the Golden House shines again

It was the late 15th century, in Rome. Pinturicchio, Filippo Lippi and Ghirlandaio were working on frescoes at the Sistine Chapel when news arrived of a cave-in on the Oppian Hill, overlooking the Colosseum. A buried grotto with ancient paintings had been found.

Dropping their brushes, the artists rushed to the site and lowered themselves into the chamber. In the torchlight, they saw magnificent vaulted ceilings, painted with brightly colored mythical scenes bordered by floral and arabesque designs in gold leaf.

This “grotto,” we now know, was a vast hall in the emperor Nero’s Domus Aurea (Golden House), much of which has now been restored and opened to the public after being closed for 20 years. Until the restoration, many of the building’s roofs risked collapse and its paintings were being obliterated by water seepage. Today, 32 of the building’s 200 rooms can be visited.

Following the cave-in 500 years ago, other artists—including Michelangelo and Raphael—visited the building. Soon ceilings throughout Rome were being decorated in the ancient style, called “grotesque,” from the word “grotto” (cave). In fact, the Domus Aurea was not a grotto: Temples and baths had been built over much of it since ancient times. The real floor was over 15 feet below the Renaissance level.

In 64 A.D., after much of Rome was destroyed by a fire, Nero confiscated acres of land right in the heart of the city. There he built a vast complex of structures, including government buildings, a temple to Venus and, on the Oppian Hill, the 013Domus Aurea.

According to archaeologist Adriano La Regina, supervisor of the restoration, Nero probably built the Domus Aurea to house the more than 100 statues he had collected while visiting Greece. “The lack of service rooms, kitchens and latrines suggests this was a museum,” Regina said.

If Nero is famous for his Hellenic tastes, he is notorious for his violent appetites. The emperor had his mother and, most likely, his divorced wife killed; he forced his former tutor, the playwright Seneca, to commit suicide; and in 68 A.D. Nero took his own life. According to the early second-century historian Suetonius, “Many of Nero’s vices were inherited, although indeed he made a ghastly caricature of his ancestors’ virtues.”

But did Nero fiddle while Rome burned? Marisa Ranieri Panetta, author of a new biography, Nerone, il Principe rosso (Nero, The Red Prince), suggests that Nero was also the victim of bad press:

“He loved Greece and its arts. He refused to have his gladiators killed in the arena. He scandalized the traditionalists of the Roman Senate by performing on stage, and by participating in athletic events. He was a pacifist who disliked war. This did not sit well with the warrior tradition of the empire.”

Three decades after Nero’s death, the emperor Trajan sealed the Domus Aurea to build a bath complex over the site—paradoxically preserving Nero’s museum for posterity.

The Domus Aurea, once again a museum, is open daily from 9 a.m.

to 10 p.m. Admission is limited, however, so it is advisable to make reservations by telephone (39–06-481–5576).

014

Boats from Underground

Archaeologists discover a lost harbor in ancient Pisa

It’s not just a cliché: Whenever a shovel pierces the Italian soil, another ancient ruin is uncovered.

In December 1998, as an Italian construction crew sunk the foundations for a new railroad signaling center about a quarter of a mile from the Leaning Tower of Pisa, they found impressive relics of ancient Rome. Archaeologists have now recovered 15 Roman and Punic boats from the site—an ancient port on the river Arno.

Work on the signaling center has been postponed repeatedly, as more than 50 archaeologists and excavators keep uncovering more of Rome’s past.

Ancient ships have been found throughout Europe, including two small barges discovered in Lake Nemi, just east of Rome. But the 15 Pisan vessels account for about a third of all European boats recovered from the deep past, and they are in nearly mint condition, with each containing part of its cargo. Portions of an ancient dock have also been uncovered.

Archaeologists now believe that Roman Pisa was a kind of lagoon city, containing several ports. The port with the 15 boats was probably first built in the fifth century B.C., and it remained in use for about 1,000 years.

The Pisan boats sunk at various times, very likely after storms had ripped them from their moorings. Over the past 1,500 years, the sea has receded three miles, leaving the ships sealed in a bed of clay silt.

Among the cargoes were terracotta amphoras from Spain, North Africa and western Greece containing food remains. Excavators have also found woven baskets, leather pouches and personal possessions of the sailors: cups and dinner plates with the owners’ names scratched on their bottoms, a gold brooch, wooden sandals with leather straps, Egyptian glass, a waxed writing tablet, needles used in mending sails, and animal bones.

The most astounding find: the skeleton of a dog clutched in the arms of a man’s skeleton. The archaeologists suggest that the man was trying to protect the dog from the storm that destroyed the boat.

Plans are being made for a museum to house the boats, but no site has yet been chosen. To preserve the wooden vessels, each must be encased in its own fiberglass cell to keep the humidity level constant; otherwise the boat would dry out too quickly, causing it to warp or to crumble into fragments. The wood is completely saturated with water and weakened from bacteria that attacked it in antiquity, before the wrecked ships were “protected” by the silt. According to Barbara Ferrini, an archaeologist at the site, it may take two years to extricate the ships from the mud.

016

The Mayor’s Digs

Sumptuous living in southern Egypt

At Abydos, on the west bank of the Nile in Upper Egypt, archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania and Yale’s Institute of Fine Arts are uncovering a 4,000-year-old house that once belonged to a town’s mayors.

The name of the ancient Egyptian town is a mouthful: Enduring-are-the-places-of-Khakaure-maa-kheru-in-Abydos. Enduring, one of very few Middle Kingdom (2040–1640 B.C.) towns that have been excavated, was built near the mortuary temple of the 12th Dynasty pharaoh Senwosret III (1878–1841 B.C.). It appears that the town’s entire population worked for the temple, which controlled a network of farms and mines. Huge granaries behind the mayor’s house once contained the community’s food supplies, which the mayor probably portioned out as payment for labor.

Excavators discovered the house in 1994. It turned out to be an immense structure 165 feet wide and 265 feet long. The building had a 14-column hall running its entire width, along with rooms, courtyards and corridors arrayed around a central block of nine rooms.

In 1997, the archaeologists found a number of seal impressions containing the names of four people who bore the mayoral title hatyaa, “foremost one” (the impression at left bears the name of Enduring’s third mayor, Nefer-her). Josef Wegner, an archaeologist with the University of Pennsylvania, told Archaeology Odyssey that the building was probably a civic complex, containing not only the mayor’s residence but also the town’s administrative offices.

Judging from the house’s remains, Wegner said, Enduring’s mayor enjoyed substantial wealth and power. In the residential wing, excavators found statue fragments; cosmetic pots for kohl (a powder used to darken the eyelids); jewelry made of faience, amethyst and carnelian; mirrors with handles of ebony and ivory, some carved in the shape of lotus flowers; and fine ceramic bowls. They also found numerous toys: a number of small clay figurines shaped like humans and animals, and pieces of the board game Hounds and Jackals (similar to Egyptian senet, a game played on a board with 20 squares).

When the Middle Kingdom collapsed in the 17th century B.C., the town of Enduring fell, too—and the site was abandoned thereafter. This neglect, however, turned out to be a blessing in disguise, for modern excavators have found the site extremely well preserved. Enduring, it seems, endures.

016

New Blood at Jordan Antiquities Department

This past summer, Fawwaz Khrayshah took over as Jordan’s new Director General of Antiquities. A former associate professor of archaeology and Semitic languages at Yarmouk University, Khrayshah is a specialist in pre-Islamic-period languages and the archaeology of the Middle East from northwest Arabia to southern Syria. He has published extensively on the Safaitic, Thamudic, Nabataean and early Arabic languages. As director general, he will oversee all of Jordan’s archaeological excavations and supervise the activities of some 450 employees.

Khrayshah took over the position from Ghazi Bisheh. A member of Archaeology Odyssey’s editorial advisory board, Bisheh served as Jordan’s director of antiquities from 1988 to 1991 and from 1994 to 1999.

018

Pepping up Pepi

Curing the world’s oldest metal statues of bronze disease

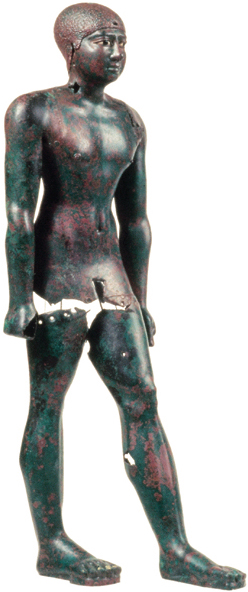

In 1897 the British archaeologist James Quibell began excavating an Old Kingdom temple at Hierakonpolis, some 400 miles south of Cairo. He soon suspected, however, that there was more to this site than met the eye. After cutting through the temple’s original floor, he discovered five underground chambers. In one lay an exquisite gold falcon. Another contained an even greater treasure: a man-size copper statue (above).

Quibell hauled the statue down the Nile to the Giza Museum. As workers began to clean the piece, they found a smaller—20-inch-high—copper statue inside the torso of the larger one. Most Egyptologists believe both statues depict Pepi I (2289–2255 B.C.), the second pharaoh of Egypt’s 6th Dynasty (though some identify the smaller statue as Pepi’s son Merenre). They are the world’s oldest known metal statues.

The problem, however, was that both statues were badly corroded. Over the millennia, much of the original copper had disintegrated into powdery copper oxide.

Unlike more durable metals, such as gold, copper deteriorates significantly over time, at a rate determined by such factors as humidity, temperature and the presence of other elements that react with copper. By the time Quibell opened the Hierakonpolis temple’s underground chambers, the Pepi statues had been undergoing this process of corrosion—and conversion into copper oxide—for 4,000 years.

To make matters worse, over the next century the statues were kept in storage—where levels of humidity and corrosive gasses (such as carbon dioxide) were much higher than they are beneath the desert sands. Big Pepi and Little Pepi were thus further damaged by what metal conservators call the post-corrosion process, in which the disintegration of the copper becomes much more rapid.

In 1996 Christian Eckmann of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum in Mainz, Germany, began restoration work on Little Pepi (above). Eckmann (below), a conservator who specializes in metal and glass, began by analyzing samples of both the corroded and the 019uncorroded copper to determine the composition of the original material. He needed to know, for instance, the amount and kind of salts naturally present in the copper, for such salts are extremely corrosive once exposed to moisture.

Eckmann also took X-ray photographs of Little Pepi to determine whether the original statue had decorations or inscriptions, whether the copper had cracked, and how much of the metal had deteriorated.

Then he removed materials used in previous restorations. Such materials as gypsum (an ingredient in plaster of paris), certain resins and linen are sometimes used to restore and reconstruct ancient artifacts—with the result that elements of the original pieces are obscured. Eckmann had to remove the surface coatings to get at the copper.

The next step was to clean the statue by removing material that had accumulated on the piece through natural processes. Cleaning is irreversible and may damage the original object, however, so it must be done meticulously. Eckmann was unable to use chemical solutions to dissolve this accumulation, for fear that they would also erode the fragile copper. So he used dental picks to remove large masses of accretion and sophisticated ultrasonic devices for the finer, more delicate work.

As the cleaning proceeded, supports were built to hold each statue firmly in a vertical position, allowing Eckmann to join the parts. In places he had to reconstruct missing areas. Because some portions of Little Pepi had been reduced to powder, Eckmann used a special epoxy resin to stabilize these weakened areas.

Even after cleaning, however, chloride ions (salts) remain present in copper, ready to eat away at the metal if it is exposed to humidity. This kind of erosion is known as “bronze disease,” because it is a common scourge of objects made of bronze (an alloy of copper and tin). The cure for bronze disease involves special treatment and appropriate storage. To protect the statue, Eckmann applied a substance called benzotriazole over its entire surface. The statue was then placed in an air-tight, nitrogen-filled case maintained at a constant temperature and level of humidity.

According to Eckmann, both Pepi statues were constructed in the same way: Copper sheets were cut to the sizes needed for specific sections of the body; then the metal was heated and hammered into shape. The sections of each statue were joined together with copper nails, which are still visible today. Little Pepi was apparently made in seven sections, assembled on a wooden armature.

Eckmann’s restoration also revealed traces of gold on Little Pepi’s toenails and fingernails. Gold may also have been used on Big Pepi’s kilt, scepter and uraeus (the cobra insignia of Egyptian pharaohs, worn on the front of the crown). Unfortunately, these parts of Little Pepi are missing. As Old Kingdom statues were commonly decorated with various colors, the two Pepis were probably once gloriously polychromatic, enhanced with reds, golds, blues and other hues.

Today, Little Pepi stands proudly in the central hall of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Without Eckmann’s miraculous conservation work, both statues would soon have been reduced to mere powder.

013

OddiFacts

Gold Rush Fever

With the help of an ancient map, a mining company has struck gold. Or hopes to. The Centamin Mining Company of Perth, Australia, is prospecting in Egypt by using a copy of an ancient papyrus now housed in a museum in Turin, Italy. The papyrus marks the locations of gold mines in the Sukkari region, a strip of desert 500 miles southeast of Cairo, during the reign of Seti I (1318–1304 B.C.). Pharaoh Gold Mines, the treasure-hunting subsidiary of Centamin, says it plans to begin mining sometime in the year 2000.

Built to Last

When the earth shook, ancient Turkish and Greek monuments stood their ground

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.