After more than two centuries, the Naples Museum’s Pornography Collection is on display once again

Anyone who doubts the selling power of sex should visit the Naples Archaelogical Museum. For almost five months now, the museum has been attracting enormous crowds with its newly reopened exhibit of ancient erotica.

Formally known as the Pornographic Collection, the museum’s exhibition consists of some 200 sexually explicit paintings, mosaics, sculptures and household items recovered from Pompeii and other ancient Roman sites.

The highlight of the exhibit is a series of murals taken from brothels and private homes in Pompeii. With their graphic depictions of men, women and gods involved in acts of copulation, these scenes (including the first-century A.D. wall painting of Hermaphroditus Struggling with a Satyr shown below) were obviously designed to titillate or amuse their viewers.

But not all of the artifacts in the Pornographic Collection were originally intended as erotica.

“The ancient Romans’ ideas of sex were quite different from ours,” said museum director Stefano De Caro, an archaeologist who has worked for many years at Pompeii. According to De Caro, Christian ethics have tinged aspects of the human body with sin, but that was not the case in ancient Rome; the Romans did not find sexual images sinful, nor they did always associate specific body parts, such as the penis, with sex.

At the entrance of the renovated museum hall, for instance, stands a 2-foot-high stone phallus. The two Etruscan names carved on its side indicate that it was not an erotic statue, but a grave marker. In this case, the large phallus was actually a religious symbol, representing the Etruscans’ belief in the afterlife.

Many other phallic objects in the collection were intended as tributes to the Greco-Roman god Priapus, who was associated not only with fertility but also with good luck and prosperity.

When archaeologists first began excavating at Pompeii in the 18th century, they were shocked to discover a 2-foot-long terracotta phallus protruding from the side of a public building. The presence of the phallus convinced the excavators that the building must have been a brothel, until someone noticed that the building’s main chamber contained a large bakery oven. “The terracotta phallus outside was meant to bring good luck to the bakers, ensuring that the bread would rise and bake properly,” said curator Marinella Lista.

Priapic door chimes, good luck charms and figurines dominate the Naples exhibit. One room contains a 2,000-year-old shop sign emblazoned with an ithyphallic Mercury (above), another symbol of luck in ancient Pompeii. There is even a playful set of 10-inch-high bronze serving platters—sculpted in the shape of well-endowed bread vendors (below). But not everything in the Pornographic Collection is phallocentric. One enormous fresco taken from a house in Pompeii features the goddess of love, Venus, reclining naked on a half shell. Nearby, another statue depicts the same goddess tastefully clad in a delicate gold appliqué bikini.

Most of the artifacts in the exhibit have been in the custody of the Naples Museum ever since they were excavated 250 years ago; but for much of that time they have been considered too shocking for public consumption. The collection was first placed off-limits by Francesco I (1825–1830), king of Naples, after he toured the museum and saw a marble statue of the shepherd god Pan copulating with a goat (below). Scandalized, Francesco decreed that all of the museum’s sexually explicit artifacts should be shut up in a secret room, to which only “persons of mature age and known morals” would be permitted access.

The secret collection was reopened briefly in 1860, and again in 1976, but then was closed down for 24 years while the museum underwent renovations. Finally unveiled to the public this past April, the new and improved Pornographic Collection is a permanent exhibition. It is open to all adults, but children under the age of l4 must have written consent from their teachers or accompanying parents. For information about ticket purchases or group reservations, contact: Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Piazza Museo 29, 80135 Naples. Tel. 39–081-544 1494.

The dean of classical archaeology

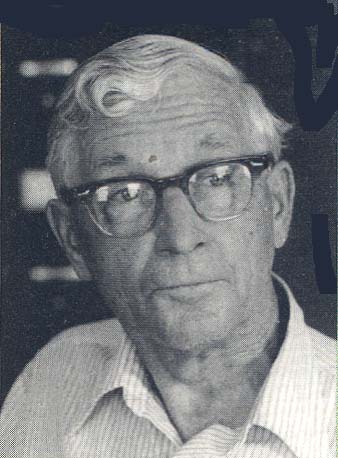

The director of one of the first major archaeological excavations in Athens, Homer Armstrong Thompson, 93, died last May at his home in Hightstown, New Jersey.

After receiving his doctorate from the University of Michigan in 1929, Thompson was asked to become a fellow in an exciting new expedition—the American School of Classical Studies’ excavation of the Athenian Agora. The Agora is often described simply as a market; in fact, for the ancient Greeks the term referred to an assembly place where the citizens of democratic Athens met and conversed with one another. By excavating the Agora, Thompson thought, archaeologists might discover the civic heart of the ancient city. He served as deputy director and director of the Agora excavations for the next 39 years.

By the time Thompson arrived in Athens, the Agora had long been known from literary sources, but no one knew exactly where it was. The expedition required two years of planning before spades struck the ground in 1931. The Agora, moreover, was not only the hub of ancient Athens; it also lies right in modern Athens. Before the dig could begin, 400 houses had to be removed.

When World War II stopped archaeological work in Greece, Thompson served as an intelligence officer in the Canadian Navy. After the war, he became a fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and then in 1949 he returned to Greece to direct the renewed Agora excavations. Among other projects, Thompson was instrumental in the excavation of the Stoa of Attalos, a two-story building that housed shops and civic buildings. (Today, the reconstructed Stoa dominates the Agora and is the site of the Agora excavation museum.)

In the spirit of those ancient Athenians who admired learning, and who no doubt discussed their ideas while strolling through the Agora, Thompson was a cherished teacher and lecturer. In addition to his scholarly publications, he published such popular works as The Athenian Agora: A Short Guide (Princeton, 1993) to pass on to a larger audience the wisdom he extricated from the ancient past.