Field Notes

012

Nola: A Prehistoric “Pompeii”

Archaeologists Uncover a Bronze Age Village Buried by Vesuvius

In May, 2001, a construction crew was ready to dig the foundation of a new shopping plaza in the Italian town of Nola, 7 miles southeast of Mount Vesuvius. Following standard procedure, the builders arranged for a preliminary survey to be conducted by archaeologists, who drilled deep beneath the surface in search of ancient remains.

Which, of course, they found. Some 21 feet below ground, they came across traces of a kiln used to smelt metals. In the ensuing excavations, the archaeologists have so far uncovered two elongated, horseshoe-shaped huts from the best-preserved Bronze Age village ever discovered in Italy.

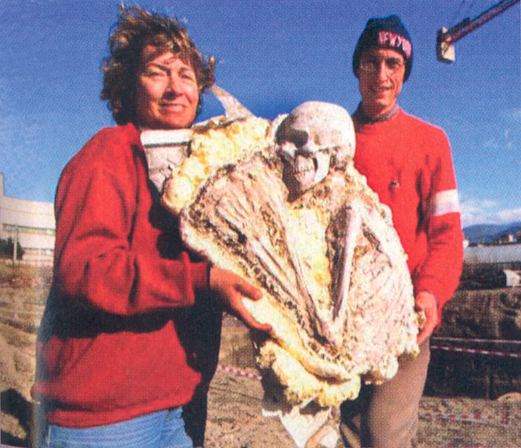

Between 1880 B.C. and 1680 B.C., Mount Vesuvius erupted, covering the prehistoric village with mud, pumice and volcanic ash. (The dates have been determined by carbon-14 analysis of skeletal and pottery remains.) Paradoxically, this destructive explosion preserved many artifacts under the hardened volcanic material. From these remains, archaeologists have even been able to recreate the villages’ huts; for as the timber and thatch of the buildings decayed away, hollow impressions (or “molds”) were left in the volcanic casing. (Similarly, the photo above shows a mold for a sheath of grain.)

To date, five Bronze Age villages have been found near Vesuvius. “Obviously there were more,” said Stefano de Caro, director of the Naples Archaeological Museum. “This shows how densely settled the area was even in prehistoric times.” But de Caro also noted that the Nola site is by far the most complete Bronze Age village yet found: “This is the first time [in Italy] we have found everything together: the dead, dwellings, crafts, customs, food.”

When a fast-moving cloud of poisonous gas and ash reached Nola more than 3,500 years ago, it blew large, hourglass-shaped clay pots of stored foodstuffs toward the back of the villagers’ dwellings. Many of the pots still contain traces of what appear to be foods or other organic substances. Some of the pots have air slits on their lower halves, suggesting that they may have been used as food warmers.

Other finds include ceramic plates and cups, a pot still standing upright in the kiln where it was being fired (see photo, above), and a round terracotta bottle similar to baby bottles used in southern Italy until a few decades ago. Excavators have also found a headdress made of polished bone tiles crowned by a ring of wild boar tusks.

Bronze Age Nola shows not just one but two occupation levels. Claude Livadie (shown above), an archaeologist working at the site, speculated that villagers lived at Nola until its surrounding fields became depleted, and then they moved on. Generations later, they returned to their ancient home, or others settled at Nola, to farm fields that had lain fallow for years.

Judging by a similar village excavated at nearby Palma Campania, Nola’s Bronze Age community probably contained about 30 dwellings, with each housing perhaps ten people. The two horseshoe-shaped huts uncovered so far are more than 50 feet long. An inverted-V-shaped stepladder found in one suggests that the hut may have had a sleeping loft. All of the huts were ingeniously constructed to protect villagers from the region’s weather conditions—chilly and sometimes rainy in winter, sun-drenched and hot in summer. Exterior walls 013were made of a thatching of dried stalks of cereal grasses that were braided, threaded through a lattice of timber beams and then covered by a layer of wet clay. An 18-inch air space between the outer and inner walls (made of plaited reeds coated by a thin layer of mud) provided insulation.

Eerily preserved in one of the village’s paths are fleeing footprints of some of Nola’s inhabitants. Skeletal remains of two trapped villagers have been uncovered at the site; their arms were found clasped over their faces, as if shielding themselves from the volcano’s fury. The villagers’ domesticated animals shared a similar fate. A large cage—raised 6 feet off the ground near one of the huts—was found with the skeletons of pregnant goats and sheep.

013

Current Exhibitions

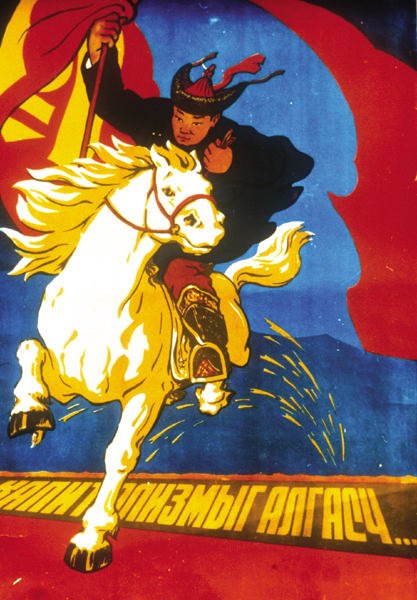

Modern Mongolia: Reclaiming Genghis Khan

Philadelphia, PA

Through June 1, 2002

Three life-size dioramas of a traditional yurt (a circular tent made of skins), along with 192 costumes and 35 archival photographs illustrating nomadic life, introduce visitors to the exotic world of 20th century Mongolian culture. Accompanying the exhibit are four films that shed light on modern Mongolia’s roots in the turbulent period of Genghis Khan (1162–1227 A.D.).

Photographic Explorations: A Century of Images in Archaeology and Anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania Museum

Philadelphia, PA

May 2, 2002–December 2002

Hundreds of photographs are on display from the museum’s 110 years of archaeological field work around the world—including expeditions to the Amazon, Egyptian Memphis, Mesopotamian Ur and Anatolian Gordion.

Ancient Empires, Syria: Land of Civilizations

Atlanta, GA

Through September 2, 2002

Artifacts from 11 museums reflect the scientific, economic, cultural and religious development of Syria’s ancient civilizations. Masterpieces from Mari, Ugarit, Ebla and Palmyra are all on display.

013

OddiFacts

Hatching an Idea

In the first century B.C., the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus reported that the Egyptians were building large brick ovens to incubate eggs. Egyptian chicken farmers checked the temperature in the ovens with only their hands—to maintain the steady, though not overly intense, heat required to hatch the eggs.

Nola: A Prehistoric “Pompeii”

Archaeologists Uncover a Bronze Age Village Buried by Vesuvius

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.