Field Notes

010

Pharaohs Reign Over Washington

Egyptian Artifacts To Tour U.S.

A spectacular exhibit of more than 100 Egyptian antiquities recently opened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The Quest for Immortality: Treasures of Ancient Egypt includes objects that have never been publicly displayed before and many that have never traveled outside of Egypt—all culled from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the Luxor Museum and the archaeological sites of Deir el-Bahari and Tanis.

“The exhibit tells what ancient Egyptians thought was going to happen to them when they died,” says exhibit curator Betsy Bryan, an Egyptologist at the Johns Hopkins University and a member of Archaeology Odyssey’s Editorial Advisory Board. Equally importantly, it explains how the deceased “could ensure the best possible outcome in the netherworld.”

For ancient Egyptians, the afterlife was not simply a metaphor—it was an actual physical place where work was done, meals were eaten and life resumed. Those who were judged by the deities to have led good lives could look forward to a bigger and better version of life on earth. “In the netherworld,” Bryan told Archaeology Odyssey, “wheat grew taller, the Nile stretched wider and everyone was garbed in their best clothing.”

Many of the exhibit’s objects were used in ancient times to assist deceased kings in their journey through the netherworld. Painted wooden boats, such as an 8-foot-long model of a river barge (above) found in the tomb of Pharaoh Amenophis II (1427–1400 B.C.), provided the king with transport through the waters of the afterlife. The sides of the Amenophis vessel are painted with scenes of Montu, the falcon-headed god of war, smiting Egypt’s enemies.

A gold pectoral of King Psusennes I (1039–991 B.C.), shown above, is adorned with images of deities whose divine magic and knowledge were thought to give protection to the deceased. Two goddesses guard a winged lapis-lazuli scarab beetle, symbolizing the rising of the sun. A winged sun disk, one of the 75 manifestations of the sun-god Re, appears in a motif repeated near the bottom of the pectoral.

The Egyptians also believed that the deceased could only be reborn if all his or her physical remains were entombed. In mummifying a body, the embalmers would place the soft inner organs of the deceased in separate jars (usually four in number) along with preservative resin. The gilded and painted wooden chest (below) of Queen Nedjmet (1087–1080 B.C.) contained four canopic jars with the queen’s viscera. A recumbent Annubis, the jackal god who oversaw 011the embalming process, was often incorporated into the design of such funerary objects.

The last room of the National Gallery exhibition contains a life-size reconstruction of the burial chamber of the New Kingdom pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 B.C.)—a warrior-king (above), sometimes called Egypt’s “Napoleon,” who waged successful campaigns in Palestine, Nubia and Syria. His tomb, discovered in 1898 in the Valley of the Kings, was scanned with lasers to create the extremely accurate, life-sized facsimile now on display.

Visitors enter a chamber with a painted ceiling resembling a star-filled sky, enclosed by walls covered with inscriptions from the Amduat (Book of the Secret Chamber), an ancient funerary text intended to be the pharaoh’s guidebook to the afterlife. The Amduat describes the 12-hour journey of the sun from dusk to dawn, from death to rebirth. With the help of over 700 deities (depicted in red and black drawings on the chamber’s walls), the pharaoh’s body and soul were believed to reunite at midnight and then achieve resurrection at sunrise.

The exhibit was originally conceived by the eminent scholar Erik Hornung, professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Basel, Switzerland. It was organized by a private Danish company, the United Exhibits Group, which acts as an intermediary between hosts and lenders, in association with the National Gallery and Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities.

The Quest for Immortality will remain in Washington through October 14, 2002, and then travel for the next five years to about a dozen cities, including Boston, Fort Worth, New Orleans, Denver and Houston.

012

A Message from the Gods?

Axum Stela Struck by Lightning

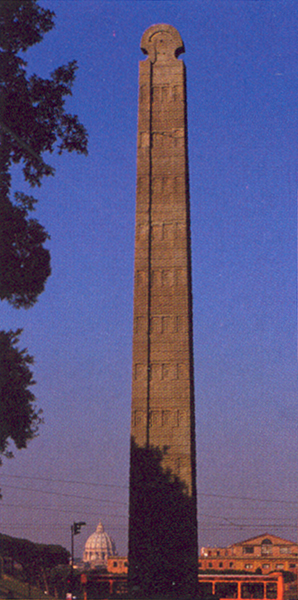

“Ethiopia Demands Its Ancient Stela … Italy Demurs.” Thus ran a headline in Field Notes, AO 05:04, in which we reported on Ethiopia’s efforts to reclaim a 78-foot-tall, 1,700-year-old obelisk (above) removed to Rome after Italy’s 1937 invasion of the African country. Just before midnight on May 27th, as that issue was going to press, the obelisk was struck by a bolt of lightning.

The lightning sheared off several chunks of stone, including a 2-foot-long slab from the top of the stela (below), but appears to have caused no serious structural damage.

Although Italy agreed to return the Axum Stela to Ethiopia in 1947, the monument still stands between Rome’s Capena Gate and the Palatine Hill. In 1997, Italy again agreed to repatriate the ancient obelisk, originally erected in the Axumite kingdom, which controlled a region of east Africa in the first millennium A.D.

This most recent agreement has fallen through principally due to the opposition of Italy’s flamboyant deputy minister for cultural heritage, the art critic and TV personality Vittorio Sgarbi. According to Sgarbi, the 200-ton stela is too heavy to transport and would not be safe in the tension-rife Ethiopian highlands.

On June 19, 2002, however, Sgarbi resigned his post, stating that he no longer shared the ministry’s goals (largely involving its promotion of contemporary art, which Sgarbi has famously called “excremental art”). So the fate of the Axum Stela remains up in the air.

012

Baby in a Bottle

Roman Infant Buried in Shipping Vessel

While excavating Roman and Punic ships in an ancient harbor uncovered in modern Pisa, archaeologists found the remains of a headless newborn baby interred in an amphora.

According to Francesco Mallegni of Pisa University, “This little skeleton had been decapitated in the manner of the ancients, presumably so that it would fit inside the amphora.” Amphoras were frequently used by the Greeks and Romans as containers for the bodies of the dead, Mallegni said. Amphora interments of stillborn infants and babies whose bones showed evidence of malaria (above) were uncovered a decade ago by a University of Arizona team excavating a mid-fifth-century B.C. cemetery 70 miles north of Rome.

Amphoras were the principal shipping containers of the Greco-Roman world, which conducted a prosperous trade in olive oil, wine and garum (fish sauce). The containers were relatively cheap and provided some protection against scavenging animals. According to New Zealand classicist John Hall, large ceramic roof tiles served the same purpose: “A tiny infant could be laid on one inverted roof tile and then covered by a second. Larger tombs were constructed for adults from bigger tiles arranged in a more complex way.”

012

OddiFacts

Mummy Mia!

During the medieval period, Egyptian mummies were shipped across the Mediterranean and ground up into a black, powdery substance thought to have wondrous medicinal properties. Noblemen often carried leather pouches containing the cure-all with them. As recently as 1920, European apothecaries stocked “Mummy Powder” for their dyspeptic customers.

Pharaohs Reign Over Washington

Egyptian Artifacts To Tour U.S.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.