Field Notes

012

Wyattville’s Folly

Leptis Magna in Surrey

Ruin-hunters disinclined to travel to Libya’s Mediterranean coast to visit ancient Leptis Magna might prefer a sojourn in England’s green and pleasant land. Corinthian columns and architectural fragments from the Roman city now stand along the shore of a large man-made lake, called Virginia Water, south of Windsor Castle.

Just how did these 2,000-year-old ruins wind up as a royal garden folly?

Back in 1816, a Colonel Warrington—the British consul-general to Tripoli—and Augustus Earle, a noted artist, visited Leptis, a former Punic caravan city rebuilt by the Roman emperor Septimius Severus around 200 A.D. The men discovered that the ancient ruins were largely covered by sand dunes, as captured in Earle’s watercolor. Warrington persuaded the Bashaw (pasha) of Tripoli to present Britain’s prince regent (later George IV) with a most unusual gift: all that could be readily extracted from the sands of Leptis Magna.

Two years later, capitals, cornices, columns and pedestals were shipped to England—where no one knew what to do with them. The ruins lay in the forecourt of the British Museum for eight years; at one point it was proposed that they be re-erected as the building’s portico. In 1826 they were transported to George IV’s private estate near Windsor, where the king’s architect, Sir Jeffrey Wyattville, created the romantic folly that still stands today on the banks of Virginia Water.

013

Hedgerows at Heathrow

The First Farms in Ancient England

A team of 80 archaeologists working near London’s Heathrow airport has uncovered evidence that early Britons began to sow their own fields as early as 2000 B.C.

Their findings push back the date that Bronze Age farmers began to fence off their own fields by 500 years, according to Tony Trueman of Framework Archaeology, a joint venture between Oxford Archaeology and Wessex Archaeology.

The archaeologists have recovered pollen from long-vanished hedges, which served as ancient field markers on the 250-acre site. By 1500 B.C. these fields cut across the Stanwell Cursus—a ceremonial pathway 2.5 miles long and 65 feet wide, which dates back to 3800 B.C. Scholars believe that this pathway linked the region’s sacred locations.

“Land was needed so much that the Cursus was used for growing crops,” said Ken Welsh, the Framework Archaeology project manager.

More than 80,000 objects representing 8,000 years of human activity have been unearthed, including 18,000 pieces of pottery, 40,000 pieces of worked flint and the only wooden bowl found in Britain dating to the Middle Bronze Age (1500–1100 B.C.). Other finds include a Neolithic stone axe, a Bronze Age log ladder and wooden bucket, and Iron Age pottery cups.

013

Current Exhibitions

The Etruscans: An Ancient Culture Revealed

Atlanta, GA

(404) 929–6300

October 4, 2003–January 4, 2004

Culled from the largest private collection of Etruscan art in Italy, this exhibition of more than 500 artifacts—including pottery, tools, games, jewelry, funeral masks and urns—explores the Etruscans’ daily life and religious beliefs.

Petra: Lost City of Stone

New York, NY

(212) 769–5100

October 18, 2003–July 6, 2004

This exhibit marks the first major cultural collaboration between Jordan and the United States, featuring more than 200 objects from overseas collections. In addition to stone sculpture, stuccowork, reliefs, ceramics and metalwork, two new finds will be exhibited: an elephant-headed capital from Petra and a frieze from a Nabataean temple at Khirbet Dharih.

From Ishtar to Aphrodite: 3200 Years of Cypriot Hellenism

New York, NY

(212) 486–4448

October 22, 2003–January 3, 2004

This exhibit takes its name from its signature piece: Aphrodite Anadyomene (Aphrodite Emerging from the Sea), a torso of the goddess excavated in 1956. The exhibit highlights the influence of Greek culture on Cyprus’s cultural development and includes 85 sculptures and terracotta, copper and marble artifacts.

014

Trimontium Man

A Skull Gets Fleshed Out

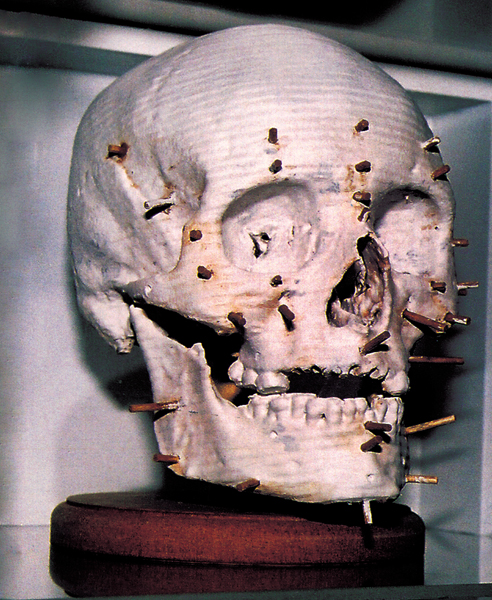

More than 150 years after being discovered by workers building a railway line close to Trimontium, a Roman fort near Melrose, Scotland, a Roman soldier has had his face reconstructed.

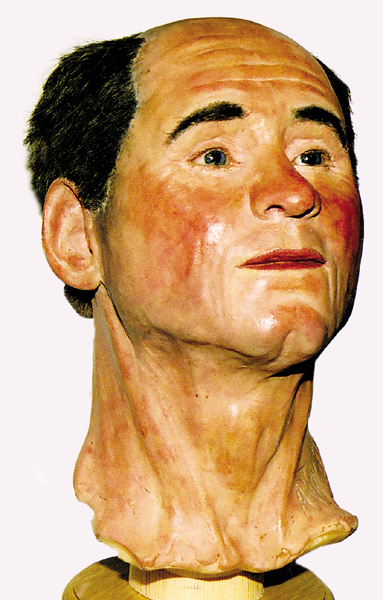

Caroline Wilkinson, of the medical art department at the University of Manchester, used a combination of forensic science and sculptural modeling to flesh out the soldier’s features. His skeleton indicated, for instance, that he was about 45 years old, and his teeth suggested that he favored the left side of his mouth for chewing and that he had thinnish lips.

The face of Trimontium Man, as the soldier has come to be called, was created using techniques originally developed to identify crime victims. After a plaster cast of the skull was produced, pegs were inserted at various anatomical points on the surface of the skull to represent average tissue depths, which are determined by an individual’s age, sex and race. Using clay, muscles were laid on one-by-one over the skull, and then the nose, ears and mouth were sculpted. After a layer of clay skin was molded over the muscle structure, the plaster-clay model was cast in wax, and the wax head was painted.

Curiously, the skeleton of Trimontium Man was found standing nearly erect in a 12-foot-deep pit, a spear by his side. Did he accidentally tumble into the pit after a night of carousing? Or was Trimontium Man a victim of foul play?

No less an expert in mystery than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was intrigued by the soldier’s death. In 1929 he wrote an eerie short story about Trimontium, entitled “Beyond the Veil.” In the story, an old farmer escorts a young couple to the excavation site and then speculates about the Roman soldier’s death:

“‘That pit was fourteen foot deep,’ said the farmer. ‘What d’ye think we dug oot from the bottom o’t? Weel, it was just the skeleton of a man wi’ a spear by his side. I’m thinkin’ he was grippin’ it when he died. Now, how cam’ a man wi’ a spear doon a hole fourteen foot deep. He wasna’ buried there, for they aye burned their dead. What make ye o’ that, mam?’

‘He sprang doon to get clear of the savages,’ said the woman.

‘Weel, it’s likely enough, and a’ the professors from Edinburgh couldna gie a better reason.’”

015

Dutch Treat

An Ancient Roman Barge Takes a Bath

Last spring, six years after it was uncovered in a construction site near the Dutch city of Utrecht, a 1,800-year-old Roman barge set out on its final journey.

After being encased in a huge steel frame, the flat-bottomed riverboat was slowly transported to the Institute of Maritime Archaeology in Lelystad. There the barge was submerged in a tank containing a chemical solution meant to preserve the ship’s waterlogged wood. In 2005, after a two-year-long bath, the boat will go on display.

The 82-foot-long, flat-bottomed vessel was remarkably intact, having been completely encased by silt in a former course of the Rhine River. The moist soil preserved not only the ship’s oak hull but also a full complement of tools and equipment: the captain’s bed and carved chest, a writing instrument with a very fine point, cooking pots and dishes. Military-issue leather sandals with spiked soles, lance points and axes were also uncovered at the site, suggesting that the barge carried a crew of two or three soldiers.

The barge’s crewmen probably supplied and maintained Rome’s fortresses and watchtowers along the Rhine—the northern fringe of the empire. Archaeologists have determined that the vessel was built in 180 A.D., when the 18-year-old Commodus became Rome’s emperor following the death of his father, Marcus Aurelius. The ship’s crew was well-equipped: iron crowbars, shears, two-handed saws and four woodworking planes have been recovered from the site.

Apparently all hands did not go down with the ship. No human remains were found anywhere near the barge.

015

Curator’s Choice

Ancient “Nails”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Glass

1st/2nd century A.D.

Two objects in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Greek and Roman Art look for all the world like modern nails.

Similar objects have been described as “pins” or “hairpins,” but it is unlikely that these items were used as either dress or hair ornaments—and they certainly were not used as nails. Their closest parallels, both in manufacturing technique and in function, are glass stirring or dipping rods that were used as cosmetic applicators throughout the Roman world.

These items were often made by twisting a rod of molten glass, though the examples in our collection don’t exhibit the spiral twist characteristic of stirring rods. The flat heads of the two Met pieces, however, do closely resemble the stud end of some stirring rods.

Our glass “nails” probably date to the first or second century A.D. Gladys Davidson Weinberg published a similar “pin,” or pointed rod, found at Jalame, the site of a glass factory in Late Roman Palestine. The Met’s two pieces, acquired in 1914 as part of the Mary Anna Palmer Draper Bequest, are said to have come from Beth Shean (ancient Scythopolis), just to the west of the Jordan River and south of the Sea of Galilee. Other pointed rods were recovered from excavations in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem in 1971.

Nails—real nails—are among the most common finds at archaeological sites, though they are rarely published. In Roman times, iron nails were normally used in timber construction work. Some ancient bronze nails recovered from Cyprus have convex circular heads that were apparently never hammered, suggesting that they, like our glass “nails,” may also have served as cosmetic applicators.

016

The Grandaddy of Mummies

Egyptian Sarcophagus Yields 5,000-Year-Old Human Remains

Earlier this year, an archaeological team headed by Zahi Hawass, head of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, discovered the oldest evidence of ancient Egyptian mummification in Saqqara, 25 miles south of Cairo. The mummy was found in a mudbrick tomb dating to Egypt’s First Dynasty (3100–2890 B.C.).

The archaeologists also uncovered 20 other mudbrick tombs nearby.

Although the ancient Egyptians were known to have embalmed dead bodies by the mid-third millennium B.C., the discovery of the Saqqara mummy reveals that human mummification in Egypt wsa practiced at lesat 500 years earlier. (The world’s earliest-known mummies were embalmed by the Chinchorro tribe of northern Chile more than 7,000 years ago.) These first Egyptian attempts at mummification were only moderately successful; remnants of skin were found in the cedar coffin that held the mummy.

016

Recent Finds

Roman Cosmetics Box

London, England

Tin

1st century A.D.

This summer, archaeologists uncovered a tin cosmetics container from the site of a major Roman temple in London. The cylindrical box was half-filled with a white cream, still imprinted with finger marks—perhaps of a Roman-British matron who used the unguent nearly 2,000 years ago. Museum of London conservator Liz Barham, seen holding the box, describes the cream as smelling “sulphurous” and “cheesy.” The year-long excavation of the temple site—located where two major Roman roads once converged—will soon conclude, clearing the way for the construction of a shopping and housing complex.

017

Sweet Tooths in the Stone Age

Did Civilization Begin with Malted Milk?

Some of the world’s first farmers may have cultivated amber fields of grain not to make bread, as the conventional wisdom goes, but malt.

University of Manchester scholar Merryn Dineley speculates that sweet malt—sprouted grain that has been toasted—may have been a welcome addition to the Neolithic diet when added to milk, which would probably only have become available once animals were domesticated about 10,000 years ago.

Last year British archaeologist Andrew Jones reported that traces of milk, barley and unidentified sugars were found in pieces of large bucket-shaped vessels at Barnhouse, a Neolithic village in Britain’s Orkney Islands.

Dineley plans to scan ancient grain samples under an electron microscope to confirm her hypothesis that the kernels were subjected to a malting process. She has a few carbonized grains from Balbridie, a Neolithic site in Scotland, and is seeking ancient Near Eastern grains as well.

Although the biochemistry behind malting has only been understood for about a century, people have made malt for millennia. The process begins when grain is steeped in water, which allows its growth hormones to activate enzymes that convert starch into sugars. The germinating grain is then toasted in an oven, which abruptly halts the germination process and creates malted grain, or malt. When malt is gently heated with water, a process known by brewers as mashing, it produces a sweet liquid.

“People began to gather wild grains and process them around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago in the Near East,” Dineley told Archaeology Odyssey. “From 4000 B.C. we have chemical evidence for beer [a main ingredient of beer is malted grain]. At some point in between, they must have worked out the various steps for making beer.”

A half century ago, the American anthropologist Robert Braidwood suggested that thirst for beer rather than hunger for bread may have been the reason our Neolithic forebears began to cultivate grain. In 1996 British archaeologist Delwen Samuel used microscopic evidence from 4,000-year-old malted-grain samples to show that Egyptians used barley to make malt for brewing beer.

Near Eastern Neolithic sites show signs of the tools needed for malting—ovens and flat surfaces to spread germinating grain.

In studying various excavation reports, Dineley has found that smooth, level floors were made as early as 10,000 years ago. She suggests that these floors may be malting floors, which might be proved with further examination. “If you find grain in association with a smooth level floor and vessels,” Dineley said, “you’ve got to start thinking that these aren’t the tools needed to make bread.”

017

OddiFacts

Siriusly Sultry

The expression “dog days of summer” evokes images of weather so scorching that panting dogs seek the shade. But the term actually refers to the Dog Star, Sirius—the brightest star in the sky. Sirius rises in near-conjunction with the sun in July and early August, leading the ancients to conclude that the combined light of these two luminaries caused the searing heat of mid-summer. In pharaonic Egypt, the annual reappearance of Sirius in the dawn sky heralded the rising of the Nile.

018

Olympic Watch 2004

Greco-Roman Sports in the Colosseum

An elegant exhibition documenting the world of sports from Homer’s Greece through imperial Rome opened last July in Rome’s Colosseum. Running through January 7, 2004, the exhibit—called Nike, after the Greek goddess of victory—features artifacts culled from Italian, German and French museums and private collections.

The Colosseum itself is an integral part of the exhibition. Until the reign of Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.), foot races and equestrian competitions were simply held in open spaces in Rome’s Campus Martius district; in later years, sports competitions were held at the Colle Oppio by the Colosseum, which was built by the emperors Vespasian and Titus from 75 to 80 A.D.

The Colosseum became the centerpiece of Rome’s first large, planned sports complex after the emperor Trajan (98–117 A.D.) demolished parts of the Domus Aurea to add extensive baths. An association of Greek athletes in Rome had their headquarters by the baths, and gladiators were barracked near the Colosseum.

The later Romans preferred spectator sports, but they also partly adopted the much older sporting tradition of Greece. Athletics lay at the heart of ancient Greek education. The first games were held in 776 B.C. in Olympia, Greece, and probably lasted just a single day. Later, competitions also took place at three other sites: Delphi, where the games were associated with religious festivities, and Nemea and Corinth, where the games were simply athletic events.

By the fifth century B.C., Greek athletic competitions had become largely formal, regularized affairs held over a six-day period. The first day was devoted to a religious procession, the ancient equivalent of modern opening-day ceremonies, and the second day to racing and wrestling events for youths. On the third day came horse races, chariot races and the pentathlon, in which contestants vied in five track-and-field events. Foot races were scheduled for day four, and on the fifth day were races for armor-clad men—vividly demonstrating the close relationship between athletics and military training. The sixth and last day was given over to festivities and award ceremonies.

At Olympia, victors tied a red band around their foreheads and donned a crown of laurel, while at Delphi, Nemea and Corinth, victory crowns were made of woven olive, 019pine or wild celery leaves.

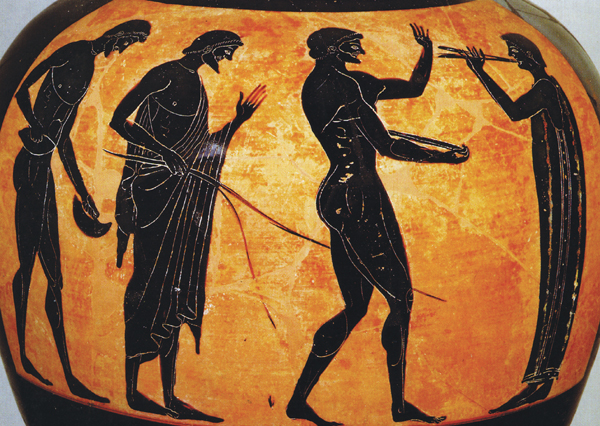

Successful athletes were idolized by the public and immortalized in sculpture. Nike showcases such magnificent life-size sculptures as the Discus Thrower (above, top), a Roman copy of a bronze by the fifth-century B.C. Greek sculptor Myron. In a 500 B.C. black-figured Attic vase (above, bottom) by the artist Kleophrades, a piper plays a double flute to facilitate the rhythmical hurling of the discus. Also depicted on this vase is a long-jumper carrying lead or stone weights, which were thought to enhance balance and increase distance. A judge standing next to the athletes holds a long stick used to measure the length of the jump.

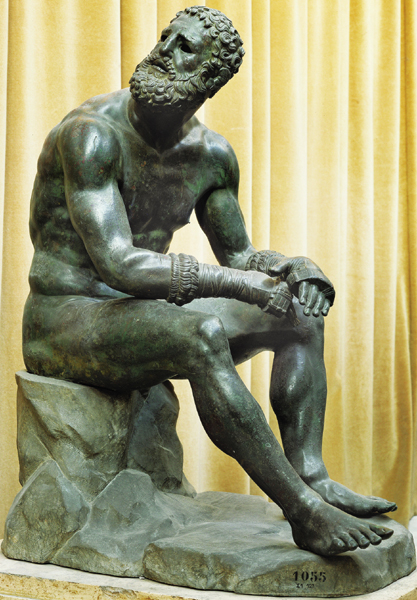

A fourth-century B.C. Greek bronze statue of a boxer (above), known as the “Puglist of the Baths,” was found on a slope of the Quirinal hillside in Rome. The pugilist is shown wearing typical boxing gloves, called himantes (detail, above). Another boxer is depicted in a third-century A.D. Roman mosaic (below); this athlete, with his thick neck and bulging muscles, was found on a floor pavement in the gymnasium at Rome’s Baths of Caracalla.

The many artifacts on display at the Colosseum bring 2,500 years of Olympics history to life. Nike should be a stop on any tourist’s upcoming Roman holiday.

Just do it!

Wyattville’s Folly

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.