Egypt’s First Kings Had Company in the Afterlife

Guided by magnetic surveys that reveal structures buried beneath the desert sands of Abydos, Egypt, 300 miles south of Cairo, American archaeologists have uncovered a First Dynasty (2920–2770 B.C.) mortuary enclosure surrounded by subsidiary graves that show strong evidence of human sacrifice.

Egypt’s earliest historical kings are buried about a mile south of this monumental enclosure, which is one of two large, open ritual spaces enclosed by mudbrick walls being excavated by a team from New York University, the University of Pennsylvania and Yale University. The smaller of the two enclosures (shown) belonged to Aha, the first king of the First Dynasty.

Archaeologists have excavated five of the six subsidiary graves surrounding Aha’s enclosure. Jar-sealings and other artifacts bearing Aha’s name were found in some of the burials; others contained jewelry made of imported lapis lazuli and ivory and the remains of strongly built wooden coffins, suggesting that the graves’ occupants were probably courtiers.

Although the subsidiary graves at Aha’s enclosure were physically separate from each other, they were covered by a continuous mud plaster floor that was created soon after the enclosure was built, indicating that the burials were all made at the same time. The archaeologists believe that various officials, artisans and servants were killed at the time of Aha’s funeral to ensure that the king’s needs would be met in the afterlife.

According to the excavation’s co-director, David O’Connor of New York University, “This rare custom [human sacrifice] is attested only for the First Dynasty and is dramatic proof of the great increase in the prestige and power of both kings and elite that occurred at this time.”

3,000-Year-Old Temple Uncovered in Syria

Syrian and German archaeologists excavating in Aleppo, Syria, have discovered 34 extraordinarily well-preserved relief panels dating to around 1000 B.C.

Images of the storm god Teshub (the head of the Hittite pantheon during this period), sparring lions (visible at right in the photo) and at least one king were carved along the northern wall of a 87- by 55-foot temple dedicated to Teshub.

The Hittites conquered Aleppo at the beginning of the 15th century B.C. and remained in control of the city at the end of the first millennium B.C. Excavation of the Hittite temple should be completed by 2005.

C-Sections

Many people mistakenly assume that the term “cesarean birth” commemorates the way the Roman dictator Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.) entered the world. But during Roman times, such surgeries were performed only if a pregnant woman were dead or dying—and Caesar’s mother Aurelia lived until 54 B.C. The term likely derived from caedare, Latin for “to cut open.”

Archaeologists Discover Ancient Lecture Halls

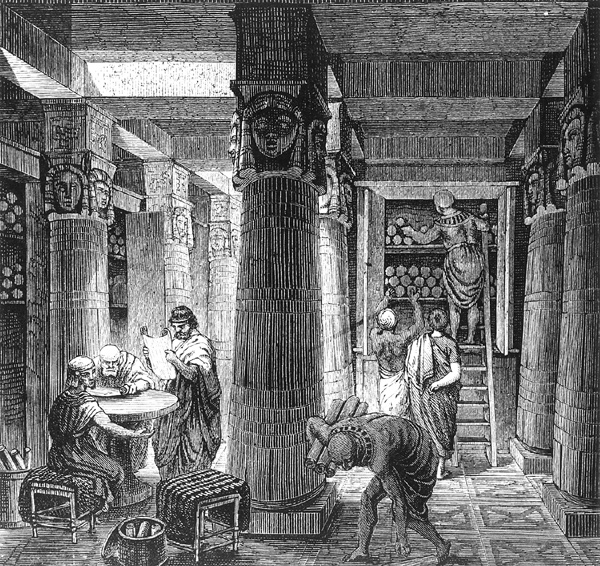

The Alexandria Library, built by the Greek-Egyptian king Ptolemy I around 300 B.C., was the greatest center of scholarship in the ancient world. The library was not only a repository of hundreds of thousands of papyrus scrolls (ancient books), but it was a research center where scholars compiled editions of Homer’s epics, scientists measured the size of the earth, and Euclid discovered the rules of geometry.

Until recently, however, all traces of the library remained hidden. Earlier this year, a Polish-Egyptian team of archaeologists excavating in the Bruchion section of Alexandria—where the royal compound of the Ptolemaic Dynasty was located—uncovered 13 large rooms, each equipped with an elevated podium. Archaeologists believe that these chambers functioned as lecture halls within the Alexandria Library.

In 48 B.C. a fire destroyed 400,000 of the library’s papyrus scrolls. In 30 B.C. Octavian (renamed Augustus by the Roman senate) conquered Alexandria and shifted the center of intellectual life to Rome. Although the Alexandria Library was never again the focal point of Western learning, it remained in use until the mid-seventh century, when it was destroyed by Arab Muslims.

Headdresses from Ancient Ur Re-discovered in British Museum Storeroom

When British Museum officials recently x-rayed two blocks of wax labeled “crushed skulls”—stored with other relics from Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavation of the royal tombs of Ur in southern Iraq—they discovered a glittering surprise. Gold and silver hair adornments, once worn by two handmaidens who were buried with their king 4,500 years ago, were embedded in the paraffin.

Because many of the grave goods uncovered by Woolley and his team from the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum were extremely fragile when they were uncovered in the 1920s and early 1930s, the archaeologists removed large blocks of material from the ground and poured melted candles over the artifacts to preserve them. Over time the wax blackened, completely obscuring the contents of the blocks.

X-rays revealed headdresses consisting of wreaths of gold leaves held together by strings of lapis lazuli beads, gold and silver ribbons, and three-pronged gold and silver combs. The reconstruction, created from other jewelry pieces found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, shows how the hair combs may originally have been worn.

Woolley recovered these objects from Ur’s “Great Death Pit,” where the remains of 68 richly attired, bejeweled women, guarded by six armed men, were uncovered. Small jars found next to some of the bodies suggest that members of the royal household willingly took anesthetics or poison before being buried along with their master.

Lattes Warrior

Lattes, France

5th century B.C.

Limestone

Life-size

The torso of a warrior, wearing a finely grooved pleated skirt, was recently uncovered in a mid-third-century B.C. house excavated near Montpellier, France. Archaeologists believe the so-called Lattes Warrior was made by indigenous Celtic-speaking people in the fifth century B.C. and reused as a doorjamb 200 years later. The figure’s body armor (two round disks can be discerned on the warrior’s chest and back, as well as the tail of a crested helmet) suggests Etruscan influence. Etruscan settlers may have resided in Lattes 2,500 years ago as part of a trade enclave.

A Hoard of Cuneiform Tablets Goes Back to Iran

The University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute recently returned a collection of 2,500-year-old Persian tablets to the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization. This repatriation of Iranian archaeological items is the first to occur since the Iranian revolution of 1979, when the shah was overthrown.

The 300 clay tablets—most of them no larger than a credit card—record administrative and legal transactions occurring during the reign of king Darius I (509–494 B.C.). Some even detail the rationing of barley and beer to adult male workers living in Egypt, Syria and Babylonia, at the far reaches of the Persian empire.

Oriental Institute scholar Richard Hallock spent 40 years translating the tablets, which are written in Elamite, an early Iranian language, in cuneiform script. Only one other person on the institute’s staff and one person in all of Iran are presently able to translate Elamite. The university hopes to establish a research agreement with that country enabling Iranian scholars to study Elamite and assess other tablets in the museum’s collection.

During the 1930s, a University of Chicago archaeological expedition to the ancient Persian capital of Persepolis returned with 15,000 to 30,000 tablets and fragments. In 1948, 179 complete tablets were repatriated; in 1951 a second set of 37,000 fragmentary tablets were returned.

Art in Roman Life: Villa to Grave

Cedar Rapids, Iowa

(319) 366–4111

through August 25, 2005

Over 200 ancient objects assembled from museum collections all over the country bring the daily lives of ancient Romans into sharp focus. The exhibit showcases Etruscan and Roman sculpture, decorative arts and frescoes in galleries designed to resemble a Roman villa.

In Stabiano: Exploring the Ancient Seaside Villas of the Roman Elite

Washington, DC

(202) 633–1000

through October 24, 2004

Exhibited for the first time outside of Italy are 72 objects from the wealthy Roman seaside resort of Stabiae, not far from Pompeii. These marble statues, wall stuccoes and ceiling frescoes were excavated 50 years ago from the volcanic ash that buried the ancient city during the 79 A.D. eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Palace and Mosque: Islamic Art from the Victoria and Albert Museum

Washington, DC

(202) 737–4215

July 18, 2004-February 6, 2005

Over 100 works of Islamic art from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London are on display; highlights include beautiful calligraphic writing from the 10th to 18th centuries and a 20-foot-high minbar (pulpit) made for a 15th-century Cairo mosque.

Games for the Gods: The Greek Athlete and the Olympic Spirit

Boston, Massachusetts

(617) 267–9300

July 21-November 28, 2004

The events of the ancient panhellenic games—such as running, discus throwing, boxing and chariot racing—are illustrated on ancient Greek vases, marbles, bronzes and coins. Artifacts from the MFA’s own collection and other museums are presented alongside photographs and videos of athletes competing in the modern games.