First Person: A Scepter from the Temple?

006

In the previous BAR, we discussed at some length whether the inscribed ivory pomegranate was authentic, and we concluded that it was.a We will not repeat that here. This article will be confined to the reasons we are confident that it is authentic.

But first a note on authenticity. To be precise, we should say we are confident it is not a forgery—for no inscription can ever be proven to be authentic. Or to put it slightly differently, an inscription can never be proven to be authentic. There is always some as-yet unknown test that would unmask the forger. Even an object excavated in a professional excavation can be a forgery; some worker, for example, may have salted the forgery in an excavation. Or it is even possible that the archaeologist who heads the excavation is a forger who planted the forged object in an excavation square to gain fame.

But let’s be reasonable. There is always a technical 007 possibility that an excavated inscription is a forgery. But that’s highly, highly, highly unlikely. So we will speak loosely—and when an object is shown beyond a reasonable doubt not to be a forgery—we will say that it is authentic even though there is this remote chance that it is a forgery.

The first reason I believe the inscribed ivory pomegranate is authentic is that experts tells me so. André Lemaire, Ada Yardeni, Robert Deutsch—internationally recognized paleographers—tell me so. Few, if any, of our readers are equipped to make an independent judgment on this. So we must rely on experts. It is relevant that no paleographer (ancient writing expert) has come out and declared the inscription to be a forgery.

Interestingly enough, the two experts in reading scripts (but not in detecting forgeries)—Shmuel Ahituv and Aaron Demsky—have declined to return to the Israel Museum to re-examine the pomegranate inscription after Ada Yardeni, André Lemaire and Robert Deutsch all have agreed that the inscription is authentic.

Although few of us can make an independent judgment, we can attempt to follow the experts’ reasoning.

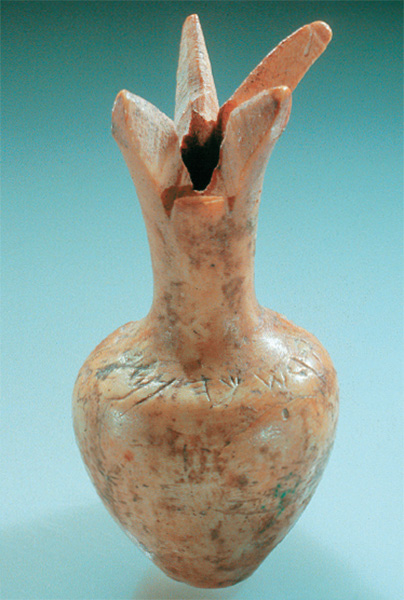

The inscription sits on the shoulder of the pomegranate ball (or grenade, as scholars call it). The inscription is only partially preserved, however, because about a third of the ball of the pomegranate has been broken off—and, of course, with it, the part of the inscription sitting on the shoulder of this part of the pomegranate ball. Actually, there are three breaks—two modern and one ancient—that have been chipped off the pomegranate ball. As a result of these breaks, several letters of the inscription are not there. And three letters of the inscription are only partially there. The original inscription, as partially reconstructed, reads as follows:

lby[t yhw]h qdsû khnm

008

“Belonging to the Tem[ple of Yahwe]h, holy to the priests.”

Here is another drawing showing the letters in a circle around a restored shoulder.

As you can see, three letters are entirely missing, and three letters are partially missing (and partially preserved). One of these letters (no. 3—yod) goes into a modern break, so it is irrelevant (this proves only that the letter was engraved before the modern break, not that it was ancient). That leaves two letters that go into the old break—or do they?

This turns out to be a crucial, determinative question. If they go into the old break, they were there before the old break and therefore the inscription must be old or, rather, ancient—and not a forgery. On the other hand, if they stop before the old break, the forger—yes, the forger—did not want to go into the old break and stopped just before reaching the break.

So the central question became whether these two letters stop before the break or go into the break.

As to the letter on the left (no. 8—a heh) the answer is still unclear. So all attention focused on the other partial letter in question—letter no. 4, a taw.

The answer is now clear. After much back and forth—as described in the previous issue of BAR—all agree that this letter does go into the old break, and therefore it provides no evidence for forgery. On the contrary, it demonstrates the opposite. The inscription is authentic.

If this is so, then there is a good chance the tiny pomegranate is the head of a scepter (there is a hole in the bottom of the pomegranate to insert the scepter rod) that was used in the Temple. The inscription (as restored) contains a mention of “Yahweh,” the Israelite God.

That this pomegranate was intended as the head of a scepter for use in a temple is suggested by the numerous similar-sized ivory pomegranates recovered elsewhere from excavations of this time period. Rods for the pomegranate scepter head have also been recovered archaeologically. An additional number of rods have been found without their pomegranates.

My own speculation is that this pomegranate was recovered in an archaeological excavation adjacent to the Temple Mount and then quickly pocketed by a workman. Or perhaps it was recovered by someone on the Temple Mount itself.

In the previous BAR, we discussed at some length whether the inscribed ivory pomegranate was authentic, and we concluded that it was.a We will not repeat that here. This article will be confined to the reasons we are confident that it is authentic. But first a note on authenticity. To be precise, we should say we are confident it is not a forgery—for no inscription can ever be proven to be authentic. Or to put it slightly differently, an inscription can never be proven to be authentic. There is always some as-yet unknown test that would unmask the forger. […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

1. Hershel Shanks, “Ivory Pomegranate: Under the Microscope at the Israel Museum,” BAR 42:02.