First Person: Bible and Archaeology

Whether or not archaeology can help us understand the Bible depends on the question.

006

More than 60 years ago, a brilliant lawyer named “Bull” Warren taught at the Harvard Law School. It was said of “Bull” Warren that it was possible to win an argument with him—but never if he put the question.

I use this to stress the significance of the question. What the question is is of utmost importance in determining the relationship of the Bible and archaeology. Whether or not archaeology can help us understand the Bible really depends on the question. In a word, don’t ask the wrong question; if you do, archaeology can be of no help.

Take the wonderful story about Samson in Judges. Born to a previously barren woman from the tribe of Dan, Samson is designated by God to be a Nazirite. No razor is to touch him. And he will deliver the Israelites from the Philistines. After he is born, the story continues almost nonchalantly: “Once Samson went down to Timnah. While in Timnah, he noticed a girl among the Philistine women … She pleased Samson” and he married her (Judges 14:1, 7–8). This unnamed woman is apparently his first wife. She (and her father) are subsequently killed by the Philistines (Judges 15:6). Samson later falls in love with Delilah, also a Philistine woman, and marries her. You know the rest of the story (Judges 16:4–30). She inveigles him into disclosing the secret of his strength (I immediately hear Delilah’s famous aria from Saint-Saens’s opera), and the deceitful woman then calls in the Philistines to cut off his hair while he sleeps. The Philistines gouge out the eyes of the now-defenseless Samson and take him in chains to work as a mill slave, endlessly turning the mill wheel like a tethered mule. Gradually, his hair grows back. His captors take him to a festival at the Gaza temple, where the blind Samson is made to dance to entertain the Philistines. Then they have him wait between two temple pillars. Samson begs the Lord for his strength just one more time. His supplication is granted. With his now-superhuman strength, he pushes the pillars apart and the building collapses. With his death, the text tells us, he killed more Philistines than in his life.

Are these stories true or not? Was there an Israelite hero named Samson or not? Archaeology can provide us with absolutely no help. Most scholars regard these stories as wonderful literary creations. Your faith may tell you that these stories are historical, that there was a Samson and he did what the Bible says he did. Archaeology can provide no assistance in settling the differences between the person of faith and the scholars who say the stories are literary creation.

But archaeology can provide some background to the stories—whether true or not. If we ask the right question, we can get an archaeological answer.

We are told that Samson “went down” to Timnah, where he found a Philistine wife. In the Biblical chronology, Samson lived in the time of the Judges, what archaeologists call Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.). Can archaeologists locate such a place for us? That’s a question we can answer. And the answer is yes.

Timnah is located in the Sorek Valley on the northern boundary of the tribe of Judah, between Beth Shemesh and Ekron (Joshua 15:10–11), both well-known and agreed-upon sites. The only contender for Timnah situated between Beth Shemesh and Ekron is the mound 084of Tel Batash, Biblical Timnah. In addition, the Assyrian monarch Sennacherib left us a cuneiform record boasting that he conquered Timnah, this at the end of the eighth century B.C. The level dating to this time at Tel Batash, excavated by Amihai Mazar of The Hebrew University, revealed a vast destruction (just as with Level III at nearby Lachish, which Sennacherib also destroyed); thus both archaeology and Biblical archaeology confirm that Tel Batash is Biblical Timnah. Archaeologists and Bible scholars alike are agreed that Timnah was located at Tel Batash.

Isn’t it a bit strange, however, that Samson, the Israelite from the tribe of Dan, would simply walk into a city of Philistines, who were the Israelite’s bitter enemies? This is another question to which archaeology might provide an answer.

The archaeologists tell us that, unlike the earliest Philistine settlement at nearby Ekron, where the Philistines first destroyed the Canaanite settlement before building their own city, no such destruction occurred at that time at Timnah. Residents of Timnah apparently “continued their life without disturbance during the first generation of Philistine settlement.”1 That is, the previous inhabitants continued living there alongside the new Philistine settlers.

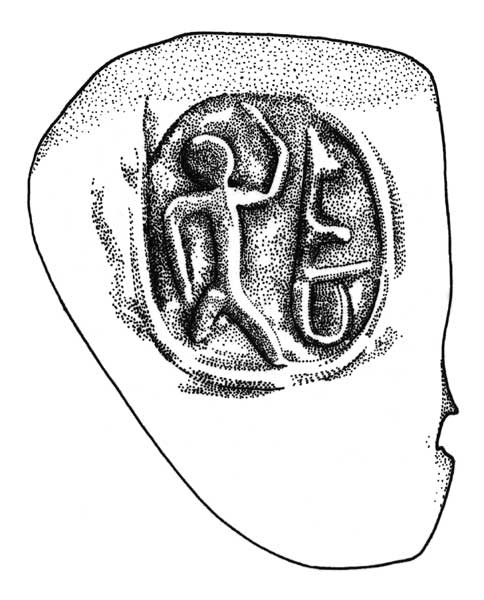

This is reflected in a very recent statistical study of the pottery by Nava Panitz-Cohen of The Hebrew University. One-third of the pottery from this particular stratum at Timnah reflected Philistine forms. The rest was a continuation of basically Canaanite forms. If only the serving vessels are counted, the number of Philistine forms increases to over 40 percent. This suggests a very mixed population in Timnah—of Canaanites, Israelites and Philistines. The Philistine presence has also been confirmed by a Philistine seal, a bulla (seal impression) and the head of a clay figurine perhaps representing a Philistine deity.

So it would seem that at this time Timnah was a mixed city with different ethnic populations living peaceably side by side. In these circumstances it would be quite natural for Samson to go down to Timnah—and to be smitten there by a Philistine girl.

But be careful not to take the next step and say that this bit of background to the Biblical story tends to confirm the Biblical story. It does not. Even modern novelists try to give a realistic context to their stories. Biblical writers did too. As the excavator of Timnah wrote: “Although the Samson narrative … is largely a literary creation, it seems that it was rooted in a geopolitical reality dating back to Iron I.”2

There is much more that archaeology can tell us about the Samson stories, especially about the conflict between the Philistines and the Israelites. But this is enough to make my point. Be careful that the questions you ask of archaeology are questions that archaeology can answer.

More than 60 years ago, a brilliant lawyer named “Bull” Warren taught at the Harvard Law School. It was said of “Bull” Warren that it was possible to win an argument with him—but never if he put the question. I use this to stress the significance of the question. What the question is is of utmost importance in determining the relationship of the Bible and archaeology. Whether or not archaeology can help us understand the Bible really depends on the question. In a word, don’t ask the wrong question; if you do, archaeology can be of no help. Take […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.