“To the prophets, God was overwhelmingly real and shatteringly present.”

—Abraham J. Heschel

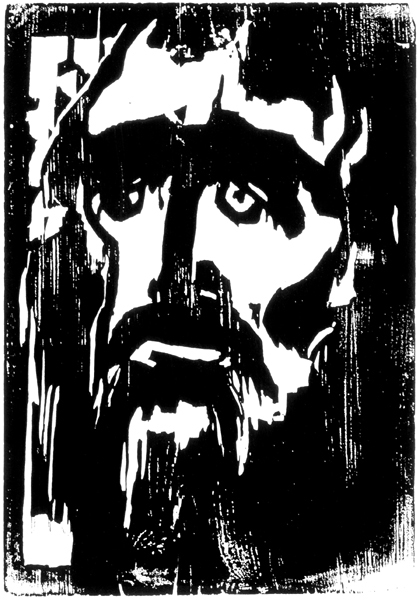

The sad eyes of the prophet—one dark, as if turned inward in deep reflection, one light, focused on the world—dominate this 1912 woodcut, titled simply “Prophet,” by the German artist Emil Nolde.

In the Bible, prophets are messengers selected to communicate God’s word—which they receive through visions, voices and dreams—to other human beings. Although they are most often called navi (translated “prophet”) in the Hebrew Bible, other titles like “seer” (ro’eh, 1 Samuel 9:9) and “visionary” (hozeh, 2 Samuel 24:1) refer to their special ability to view things that remain invisible to most people. God tells Jeremiah to direct his prophecy to those who do not have his vision: “Declare this in the house of Jacob, proclaim it in Judah: ‘Hear this, O foolish and senseless people, who have eyes but do not see, who have ears but do not hear’” (Jeremiah 5:20–21).

Some prophets eagerly accept their role as conduit of God’s message: When God asks, “Whom shall I send?” Isaiah answers, “Here am I; send me” (Isaiah 6:8). Nolde’s introspective portrait captures a more reluctant prophet, however; greatness has been thrust upon him. He is more like Jeremiah, who responds to God’s command, “Truly I do not know how to speak, for I am only a boy” (Jeremiah 1:6). Jeremiah seems to fear the visions he will be called upon to communicate. As an artist who shares this vatic ability to observe and convey, Nolde portrays the prophet’s impossible position between two worlds—seeing the divine and suffering the human.