Ashlars, Bosses, Margins, Headers and Stretchers

Stone, being more plentiful than wood and more durable than mudbrick, always served as a preferred building material in the lands of the Bible. Although the types of stone commonly used in construction varied according to region—limestone in the hill country, kurkar, or sandstone, along the coast and basalt in the Upper Galilee, Golan and Bashan—ancient stone masons frequently utilized uniform building techniques. Although it is not possible to date styles of stone construction with the same precision as pottery forms, styles of stone dressing do offer some information to archaeologists about the possible date of a building.

Ashlar

This term describes building stones that have been smoothly squared on all six sides. Although ashlars were used in the construction of the pyramids and temples of Egypt in the Early Dynastic period (c. 2920, c. 2575 B.C.), their extensive use in the architecture of the neighboring lands began only in the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550–c. 1200 B.C.). In that period, ashlars were primarily decorative, being utilized for door jambs, lintels and, in some cases, for the facing of rubble-filled walls. Among the best examples of Late Bronze Age ashlar work are structures excavated at Kition and Enkomi on Cyprus, at Ugarit on the Syrian coast and at the Canaanite cities of Gezer, Hazer, Jerusalem, Megiddo and Taanach.

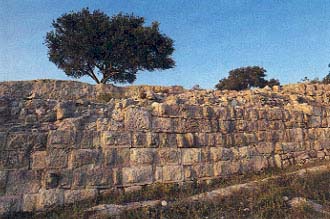

During the period of the Israelite and Judahite kingdoms (c. 1000–586 B.C.), ashlars were also used to reinforce city gates and walls at vulnerable points, as can be seen in Megiddo, Hazer, Gezer and Ashdod. One of the most impressive examples of Iron Age ashlar construction can be seen at Samaria, capital of the northern kingdom of Israel from 876 B.C. to its conquest by the Assyrians in 721 B.C. The inner wall of Samaria’s Israelite citadel is constructed of finely hewn ashlar blocks, fitted together without mortar in a complex arrangement of headers and stretchers (see below).

Ashlars were sometimes used as a strengthening element within walls as well. At Megiddo, as early as the tenth century B.C., piers, or vertical wall sections built entirely of ashlars were placed at intervals in walls built mainly of rubble or small, irregular stones. This construction technique, also discovered at Dor, Acco, Tyre and other sites along the Phoenician coast, remained popular throughout the Persian and Hellenistic periods (c. 538–c. 60 B.C.).

During the Hellenistic period, large public structures were sometimes constructed entirely from ashlars, as was the case with the massive round towers and fortification systems of Samaria and Acco. The most impressive use of ashlar construction, however, came with the building projects of Herod the Great (37–4 B.C.) at, for example, Jerusalem, Hebron, Caesarea, Masada and Herodium. Ashlar construction was also utilized in the architecture of the Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad, Crusader and Ottoman periods.

Headers and Stretchers

These terms refer to the positioning of ashlars within a wall. Since ashlars were often quarried as narrow, elongated tablets, they could be laid either lengthwise or crosswise in a wall. A “header” is an ashlar laid across a wall so that only its narrow end is visible. A “stretcher” is an ashlar laid along the length of the wall so that its long side is visible. Headers and stretchers can be laid in a great number of possible combinations; the excavators of Dor have distinguished at least 12 common patterns.

Margins

Margins are the smoothed edges along the sides of an ashlar, chipped away to provide an easier and more regular joint in wall construction. Some of the earliest examples of this technique of stone finishing can be seen in the foundation courses of the lower Israelite wall at Samaria. Margins were regularly used in ashlar construction in the Hellenistic period (c. 332–60 B.C.) and reached their most stylized form in the Herodian period (c. 30 B.C.–70 A.D.) in the exterior walls of the Temple platform in Jerusalem and the Machpelah cave complex of Hebron.

Boss

The boss is the raised center of an ashlar face, within the margins. Before the Roman and Herodian periods, homes were carved, for the most part, only on the stones of a structure’s lowest foundation courses, which would be buried and therefore not visible. This seems to be the case with the lower Israelite wall at Samaria. Eventually, however, bosses came to be accepted as architectural decoration. Contrasting styles of bosses and margins can be seen clearly in the so-called straight joint in the eastern wall of the Temple platform in Jerusalem, where the Herodian-period ashlars, with their precisely hewn margins and smooth, low bosses, are set against smaller and rougher symmetrical ashlars that were used in an earlier stage of the construction of the Temple platform.

BAR welcomes your ideas for “Glossary” articles. If you would like to write a Glossary, please send the first paragraph and a one-paragraph précis to BAR Editorial Office, 3000 Connecticut Ave. NW, Suite 300, Washington, DC 20008.