Glossary: Tools of the Archaeological Trade

068

Few of the tools used by archaeologists are exclusive to archaeology in the way a stethoscope is to a physician. Some are simple garden-variety solutions to straightforward problems. Others, especially in recent years, apply modern technology to record-keeping and to “seeing” beneath the surface of the ground.

Archaeological tools serve three objectives: to identify a place to dig; to expose structures and artifacts belonging to different strata occupied at different periods; and to record the location of all finds so that exact reconstruction is possible when all physical evidence is removed from the dig site. Let’s look at some tools used to meet these three objectives.

Searching

Ground penetrating radar (GPR): This sophisticated technology, an outgrowth of space exploration, is a relatively new—and expensive—addition to the archaeologist’s arsenal. It operates on the same principle as police radar and was used for quite some time by civil and soil engineers to “look” into the ground in search of buried pipes, soil and rock formations, water sources and the like. The American military used GPR in Vietnam to pinpoint land mines. In archaeology GPR is used not only to locate buried features such as walls, tombs and cisterns, but also to detect changes in soil layers or cavities in rocks. GPR does not replace digging, however, because it helps only in locating—but not in identifying—features. Ground scanning helps archaeologists concentrate on the area where maximum results are likely to be achieved. While they do not replace actual excavations, GPR and related high-tech tools maximize the yield. Archaeologists who do not have the benefit of GPR must rely on the older methods of digging probes and test pits.

Exposing

Gooffah (Arabic for “basket”): This is the basic piece of equipment for removal of dirt from excavated areas. Modern gooffahs are made of discarded tires, with a bottom and two handles attached to the round body with screws. A very good way to recycle old tires!

Trowel (the “Marshalltown”): Archaeologists use several hand tools, including the patishe, brushes of different sizes and shovels and hoes of various shapes. One of the most frequently used tools is the trowel, which loosens dirt, clears burials and “traces” (exposes) floors by removing the ash and/or mudbrick debris lying on the floor surface. A good trowel should be pointy, thin but strong, flexible rather than rigid and well balanced. The Stradivarius of trowels is made in different sizes by a company named Marshalltown.

Patishe (Hebrew for “hammer”): This popular tool is a small pick used to loosen dirt when conditions call for delicate work. Its head is about 8 inches long and the handle, with its wooden grip, is about 16 inches long. The head has one pointed end for picking and an adze-like tip for scraping. Unlike a large pick, it is handled with one hand.

Sifter, screen: Many situations call for sifting the dirt removed from the ground in 069order to search for small finds, such as coins, beads, shells, bones and seeds. There are several methods for accomplishing this, one of which is dry sifting. Sifting is done with a screen of small mesh that allows the dirt to fall through while retaining small stones and other sought-after items. The screen is attached to a rectangular wooden frame. The sifter can be hung from a tripod or a branch of a tree, or it can be placed directly on top of a wheelbarrow. The screen is then moved back and forth, or a trowel is used to move the dirt through the screen. It takes sharp eyes to detect the small objects that are left after sifting.

A second method is flotation. Soil is placed into a tank of water, supplemented on occasion with chemical additives, to separate organic remains (wood, seed, bone, charcoal), which tend to float, from inorganic matter, which tends to sink. The organic remains can then be skimmed off the top.

Recording

Computers: The last two decades have seen the introduction of large and small computers into field archaeology and archaeological publication.a Many expeditions today use personal computers and laptops for recording data in the field. Myriads of archaeological data—including location, description, drawings, date found, special features and quantities of pottery, coins, jewelry, tools, and seed and bone samples—can be stored, sorted and retrieved quickly with the help of computers. Computers avoid mistakes in computation and can produce reports or generate lists at the end of a field season faster and more accurately than archaeologists working manually on paper.

The computer’s graphic capability can produce pottery drawings (either of sherds or of whole vessels), plans, maps and sections. Computers can also supply answers to hypothetical questions, and researchers can “restore” a vessel or a structure on screen before attempting to restore the actual object. It is possible to generate a computer image of a complete vessel from a fragment of that vessel. The rapid development of simple and inexpensive desktop publishing offers the possibility of breaking the logjam of unpublished excavation reports by making data available quickly to other scholars.

Datum point (DP): Although a datum point is not a tool, it is a means for utilizing recording tools. Progress during excavations is measured by “taking levels” (see also under “transit”) at the beginning and end of each day. To be able to take levels, a datum point is established near every excavation area. Archaeologists derive the elevation of the DP from a nearby feature whose elevation above sea level is known from national topographic surveys. The archaeologist pinpoints the DP in the field with a stake, a large nail or a mark on a permanent feature, such as a rock, and uses it as a fixed point from which to relate measured elevations (see “transit” and “line level”). Levels are taken to record the exact findspot of objects and the foundation levels and heights of walls, pillars, installations and surfaces.

Joshua or Josh cloth: Named after the Biblical military leader who stopped the sun and the moon (Joshua 10:12–13), this large cloth, preferably dark, is used to cast shade on an area while it is photographed. Light conditions must be controlled to bring out archaeological details. The best time for archaeological photography is just before sunrise, when the light is soft. At that time there are no distracting shadows and the colors are not bleached out by the harsh sun. However, sometimes it is necessary to photograph a find in situ immediately after its discovery, when light conditions are not quite as good. That is when the Josh cloth is pressed into action, shading the photographed area and eliminating shadows.

Line level: Used for taking elevations, the line level—a variation on the familiar 070carpenter’s level—is made of a narrow plastic or metal pipe closed on both ends, with a small glass window in the middle filled with liquid and an air bubble. The pipe is hung by two hooks on a line with one end at the datum point (see definition above) and the other directly above the spot whose level is to be measured. When the air bubble rests between the two marked lines in the glass window, the vertical distance between the line and the spot is measured. That number is deducted from the known altitude of the datum point to give the absolute distance above sea level of the findspot.

Meter stick: Archaeologists employ the metric system because it is easier to use than the English system of inches, feet and yards and more commonly used around the world. Meter sticks are divided into units marked with different colors. They are often placed next to objects in photographs. For large objects the stick may be divided into color blocks of 10 or 50 centimeters. For small objects, the scale used in a photograph is usually divided into single centimeters.

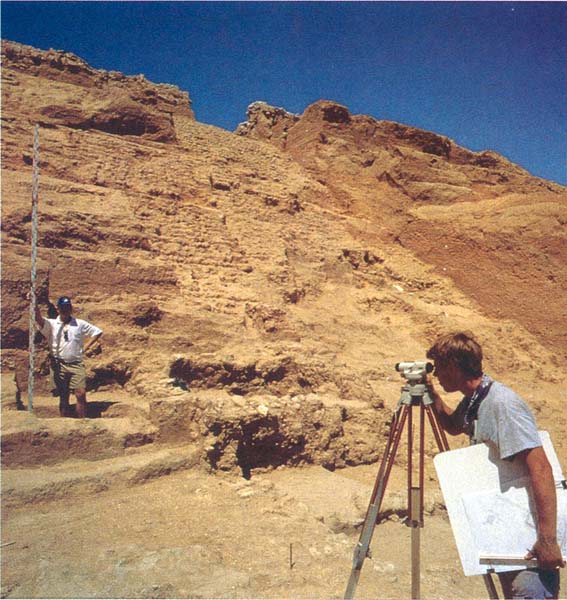

Transit, leveler: This is an instrument for level taking that is more precise than the line level. It is made of a telescope with cross-hair, a compass and levels with air bubbles (as in a line level), all resting on a tripod. A transit can be rotated 360 degrees. It is operated by two people, one holding a measuring rod vertically above, first, the datum point and then over the point whose level is sought; the other person sets the instrument level and uses the telescope to determine its elevation by noting the cross hair’s position on the measuring rod relative to the datum point (for example 1.2 meters [four feet]). The transit is next rotated to face the findspot and the measuring rod is placed above that point. If the cross hair is now at 1.8 meters (six feet) on the rod, we know that the find is located 0.6 meters (two feet) lower than the datum point.

Few of the tools used by archaeologists are exclusive to archaeology in the way a stethoscope is to a physician. Some are simple garden-variety solutions to straightforward problems. Others, especially in recent years, apply modern technology to record-keeping and to “seeing” beneath the surface of the ground. Archaeological tools serve three objectives: to identify a place to dig; to expose structures and artifacts belonging to different strata occupied at different periods; and to record the location of all finds so that exact reconstruction is possible when all physical evidence is removed from the dig site. Let’s look at some […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

See Harrison Eiteljorg II, “Reconstructing with Computers,” BAR 17:04.