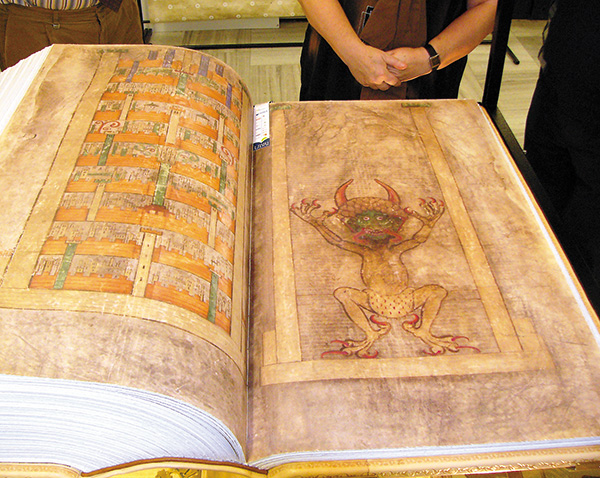

The largest medieval manuscript, the Codex Gigas—otherwise known as the “Devil’s Bible”—measures 3 feet tall and 1.6 feet wide. It is comprised of 310 parchment leaves on which both the Old Testament and New Testament are penned, as well as works by Josephus, a history of Bohemia, several medical texts and other compositions. How many scribes participated in transcribing the texts in the Codex Gigas?

Answer: One

A single scribe wrote the Codex Gigas—or the “Devil’s Bible”—the largest surviving medieval Latin manuscript.1 This scribe is also responsible for all of the manuscript’s decorations—from the elaborate initials to the full-page illustrations.

While the identity of the scribe and exact origin of the manuscript are unknown, it has been ascertained that the Codex Gigas was made in Bohemia (modern day Czech Republic) in the early thirteenth century, possibly at the Podlažice Monastery since there is a note in the manuscript that records the transfer of the manuscript from the monks of Podlažice to those at Sedlec in 1295.

The full-page portrait of the devil that appears in the Codex Gigas earned it the name the “Devil’s Bible” and spawned many interesting legends about this manuscript. According to one medieval legend, a monk of Podlažice, who had been sentenced to vivisepulture—being buried alive—for punishment of his sins wrote the Codex Gigas in one night with the supernatural help of the devil:

A monk of Podlažice walled up alive for his sins … attempted to expiate his guilt by writing the world’s biggest book in a single night. Realizing the task to be beyond his powers, he invoked the aid of the Devil. The Devil aided him, had his portrait painted in the book and demanded the monk’s soul as payment. The monk was rescued but lost his peace of mind, until finally he turned to the Holy Virgin, beseeching her to save him. She agreed to help, but the penitent died on the very point of being absolved from his pact with the Devil.2

This legend bears a resemblance to the story of Faust, as well as to Theophilus the Penitent, a popular medieval tale.

Ten texts appear in the Codex Gigas. In addition to a complete Bible, the Codex Gigas also contains five long texts and four short texts. The long texts include The Antiquities and The Jewish War by Josephus, Etymologiae by Isidore (the popular encyclopedia of the Middle Ages written in the seventh century), a collection of medical works and the Chronicle of Bohemia by Cosmas from Prague. (This first history of Bohemia was penned in the 12th century.) The short texts include a work on penitence, which is followed by a picture of the Heavenly City, a work on exorcising evil spirits, which is accompanied by the devil’s portrait, a calendar with lists of saints and important Bohemian persons and, finally, the Rule of St. Benedict, a guide to monastic life from the sixth century. The latter work, the Rule of St. Benedict, is lost; it was cut out of the manuscript.

In addition to being called the Codex Gigas (Giant Book), the manuscript has also gone by the following descriptive and ominous names: Codex Giganteus (the Giant Book), Gigas librorum (the Book Giant), Svartboken (the Black Book), Hin Håles Bibel (Old Nick’s Bible) and Fans Bibel (the Devil’s Bible).3

The Codex Gigas was taken to Sweden during the Thirty Years’ War and currently resides in the National Library of Sweden, where it is on display in their “Treasures” exhibit.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

For the bulk of these, see Nahman Avigad, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals, revised and completed by Benjamin Sass (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1997); Nahman Avigad, Michael Heltzer and André Lemaire, West Semitic Seals: Eighth–Sixth Centuries B.C.E. (Haifa: University of Haifa, 2000); Robert Deutsch and André Lemaire, Biblical Period Personal Seals in the Shlomo Moussaeiff Collection (Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publications, 2000).

2.

Source: Ronny Reich and Benjamin Sass, “Three Hebrew Seals from the Iron Age Tombs at Mamillah, Jerusalem,” in Yairah Amit et al., eds., Essays on Ancient Israel in Its Near Eastern Context: A Tribute to Nadav Na’aman (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2006).