“In the beginning was the word” (John 1:1)—but what is a word?

A “word” is a thing, a concept, that seems clear from afar, but gets fuzzier the harder we look at it. Within English, is “birthday” one word or two? What about “wedding day”? If you thought it was obvious that “birthday” is one word but “wedding day” two, it is because of the way they are written.

Similarly, what gives us the idea that a written sentence is made up of individual words? Presumably, this has to do with the fact that we can extract a part of the sentence and put it into a different sentence. But the process of transforming speech into comprehensible writing is trickier than we might realize. In regular speech, we don’t hear “spaces” between words. Instead, speech is just a steady stream of sounds: itwouldsoundverystrangeifwepausedbetweenwords.

Ancient scribes did have an idea of what made a word. We know this from word lists that we have from both ancient Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt. Scribes organized their world into categories: a list of “trees and other things made out of wood”; a list of “body parts”; a list of “animals and cuts of meat”; and so on. There are no verbs or adjectives in any of these lists, only nouns, which were copied over and over by scribes for thousands of years. They show that already at the beginning of writing, people—at least literate people—had a sense that language consisted of words.

Although they seem to know what a “word” is, Mesopotamian scribes did not include any indication of the boundaries of words within their writings. In a cuneiform text, there is no visual indication of where words begin or end. Egyptian scribes did have specific signs, called “classifiers,” which marked the end of most words. These include the common plural sign (three short strokes) and the seated woman and seated man signs. When you reach one of these, you know the word has ended.

Surprisingly, the early alphabet made things worse. The alphabet was invented, probably in the Sinai or in Egypt, just after 2000 B.C.E. In the earliest alphabetic writing, there were no spaces at all.

Even worse, in some of the texts the same letter served as the end of one word and the beginning of the next! In a common phrase found at Serabit el-Khadem in the Sinai, we read m’hb‘lt, “beloved of the Lady”—but the bet in the middle was both the last letter of the word “beloved” and the first letter of the word “the Lady.” This would be like writing “joinow” for join now or “hotamale” for hot tamale.

The genius (and challenge) of the alphabet was that it was one sign for one sound. In principle, all I have to do is say something under my breath, and I can write it down, sign after sign. But this brings us back to our initial problem: There are no pauses between words when I say them, so do I write a space between words when I write them? Probably not. So alphabetic writers of 4,000 years ago may not have had a clear sense of where words began or ended when they wrote. In fact, it took many more centuries until word dividers were introduced, and spaces are not found in alphabetic writing until about 1,200 years after the invention of the alphabet.a

It is very difficult to read a text that has no spaces: Sentenceswithnospacesgivetheeyenocluesastowheretolooktoidentifythewordsanditturnsoutthatthismakesreadingsignificantlyslowerandlessefficient. Since our brains read by “jumping” our eyes from word to word (the technical term is the French saccade, a jerky movement), we need something visual to tell us where a word begins and ends. It does not have to be spaces: Alternatingboldandnotboldworkswelltoo, asːdoːmarksːofːdifferentːshapesːasːlong?asːtheyːtellːusːwhereːeachːwordːends.

So how were the early alphabetic texts read? With no spaces or word dividers, how did anyone know what the texts said?

One possibility is that people read aloud. The medievalist Paul Saenger showed that, in classical and medieval texts, the introduction of spaces went along with silent reading. For centuries, European reading was out loud, and it turns out that spaces are less important. THISMAYBEHARDTOREADWITHYOUREYESBUTTRYTOREADITOUTLOUDANDITWILLBEMUCHEASIER. So perhaps the early alphabetic texts were also meant to be read out loud. Many have observed that the Hebrew word for “read,” qara, is really the word meaning “to call,” suggesting that “to read” was originally “to call a text aloud.”

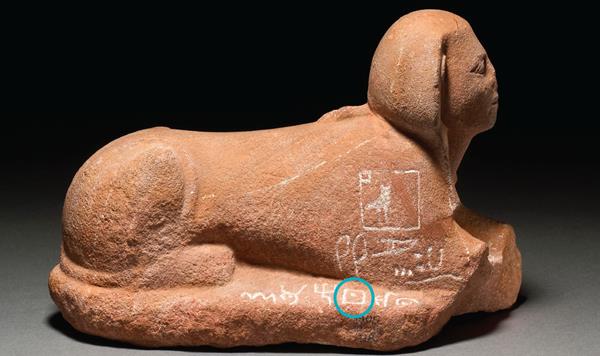

But in many of the early alphabetic cases, there is even a simpler explanation: They were not meant to be read at all! The inscribed miniature sphinx from Serabit el-Khadem (opposite), for example, was dedicated to the goddess Hathor and deposited at her temple. Its early alphabetic inscription, then, was supposed to be read only by a deity—and it is likely that goddesses can read even without spaces.

We moderns take for granted that we write for someone else to read. But ancient writing did not always serve this purpose: Some writing was done for the purpose of writing alone. This is not entirely foreign to us. Journaling is often done for the purpose of purely writing, with no intention of anyone ever reading it. Notes tucked between the stones of the Western Wall in Jerusalem are not meant to be read again, except (as in the case of Serabit el-Khadem) by a deity.

The ways in which ancient texts are written, then, can help us think about why they were written. People used the new alphabetic writing to express themselves, to put their words down on paper—or on stone, as the case may be. They were not writing for other people, though. In reading these texts, we are eavesdropping on a monologue that was never meant to be overheard.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. See Alan R. Millard, “Were Words Separated in Ancient Hebrew Writing?” Bible Review, June 1992.