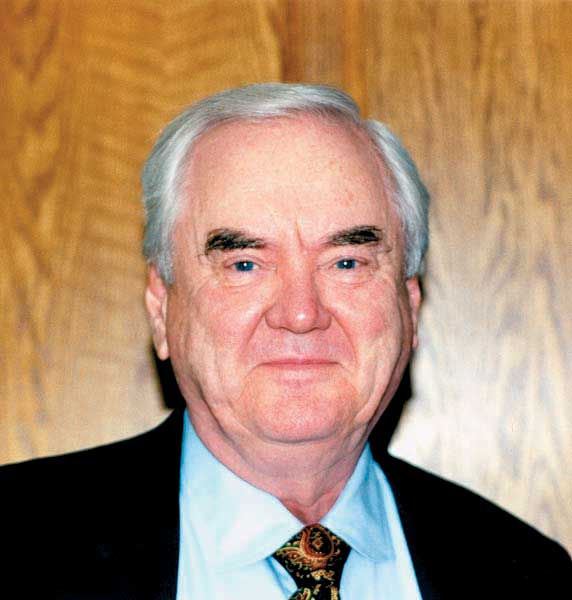

Robert W. Funk, the founder of the Jesus Seminar and Scholars Press, and the former executive secretary and past-president of the Society of Biblical Literature, has died at age 79. He was one of the most important figures in 20th-century New Testament scholarship.

Funk made his first significant contribution in 1961, when he translated from German and then revised the Greek grammar of Blass and Debrunner for English-speaking audiences. “Blass, Debrunner, Funk” quickly became, and remains, the standard reference tool for students and translators of the Greek New Testament.

In the 1960s Funk became a key figure in the movement known as the New Hermeneutic, which brought on the “linguistic turn” in American and European biblical interpretation. It was at the urging of Funk, and colleagues such as Amos Wilder and Dan Via in the Society of Biblical Literature’s Parables Seminar, that biblical scholars began to attend to the power of language to create and shape worldview. Funk’s book, Language, Hermeneutic, and the Word of God (1966) is widely regarded as a landmark in the New Hermeneutic. His essay in that volume, “The Good Samaritan as Metaphor,” is usually credited with shifting the modern interpretation of Jesus’ parables from understanding them as allegories or example stories to reading them as narrative metaphors. To capture this subtle aspect of the parables, Funk borrowed a phrase from Heideggarian linguistic philosophy: Sprachereignis, or “language event.” In the parables, Jesus used language and the power of narrative to create an event in the imagination of his hearers, through which the world might be imagined anew.

In the late 1960s, Funk was at the center of a small group of younger scholars who moved to dramatically reshape the face of biblical scholarship in North America. In 1968 Funk became executive secretary of the Society of Biblical Literature. Under his leadership, the rules for membership in the society were changed to allow for much broader participation from scholars outside of the older elite institutions. Within a few years the membership of the society had grown from a few hundred to include thousands of new members, drawn mostly from smaller colleges, seminaries and university religion departments. The society also began meeting jointly with the American Academy of Religion in order to encourage the cross-fertilization of diverse fields in religious studies. By the late 1970s, the joint annual meeting of the SBL and the AAR was drawing several thousand participants and had become the largest gathering of scholars in religion in the world.

In 1974 Funk founded the journal Semeia to accommodate the more experimental approaches to biblical scholarship that began to emerge at this very creative time in American scholarship. The first volume of Semeia, which Funk edited, was devoted to biblical studies and Structuralism. This was one of the first attempts to bring to the Bible questions that the French Structuralists (and later Post-Structuralists) were posing about the deep structures and unarticulated meanings that lay beneath the surface of a text. Volume 4, edited by John Dominic Crossan, introduced biblical scholars to the work of Paul Ricoeur (1913–2005), the French-born philosopher of existentialism and interpretation theory. In these early volumes of Semeia lie the roots of what would soon become a flourishing of literary-critical studies of the Bible among North American scholars.

At about the same time, Funk proposed the creation of Scholars Press, on the gambit that serious scholarship in religious studies, including Ph.D. dissertations, might find a market in North America similar to that in Europe. Against much skepticism, Scholars Press was founded in 1974 with Funk as its first director. For more than 30 years it provided a publication outlet for high-level, technical scholarship across a variety of fields in religious studies. These efforts arguably put North American scholarship on a course to become the center of creativity and productivity that it is today.

In 1985, Funk undertook his most ambitious and public project, the Jesus Seminar. Expressing frustration with the virtual invisibility of biblical scholars in the then current climate dominated by television evangelism and the rise of the religious right, Funk invited 50 preeminent New Testament scholars to join him in posing anew the question of the historical Jesus, long a locus classicus of New Testament scholarship. But this time Funk proposed that the Jesus Seminar pursue the question in such a way that a broad American public could see at work the methods and suppositions of modern biblical scholarship. Funk invited the media to listen in on the seminar’s discussions, and insisted on methods that would be easily comprehended by outsiders—such as capping each session of the Jesus Seminar with a vote, in which scholars expressed their considered judgment about a saying of Jesus by dropping colored beads into a box: red for authentic, black for inauthentic, and pink and gray for the shades in between. Funk’s press releases about the most recent findings of the Jesus Seminar often made headline news and sparked controversy. The firestorm that followed from the seminar’s disclosures brought Funk into the public limelight, along with other prominent members of the seminar, such as Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan, and made the seminar a lightning rod in the culture wars that raged through the 1990s. But it also helped to bring the historical Jesus back into the mainstream of Christian theological reflection, dramatically changing the direction of liberal Christian thinking in North America.

Funk was born on July 18, 1926, in Evansville, Indiana. He received degrees from Butler University, Christian Theological Seminary and Vanderbilt University, where he earned a Ph.D. in 1953. He held teaching posts at Texas Christian University, Harvard, Emory, Drew, Vanderbilt, the American Schools of Oriental Research in Jerusalem and the University of Montana. He was also a Guggenheim Fellow and a Senior Fulbright Scholar. He died at his home in Santa Rosa, California, on September 3, 2005.—Stephen J. Patterson, Eden Theological Seminary

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Oct. 26, 2005 to Jan. 29, 2006

www.metmuseum.org; (212) 535–7710

The first American retrospective of Fra Angelico (1390/5–1455) features 80 drawings, manuscript illuminations and paintings, including this “Angel,” by the early Renaissance master and Dominican friar (fra stands for “brother”).

From “What’s Love Got to Do with It?” through “Love Me Tender” to “All You Need Is Love,” it is apparent that at least one biblical concept—“Love Thy Neighbor” (Leviticus 19:18)—has wide currency in contemporary popular culture.

Take, for example, this headline’s admonition: “Love thy neighbor, except during the Eurovision Song Contest.” From the accompanying article, we learn that “the neighbors of Caroline Krook, a top official with the Swedish Protestant church, were enjoying the out-of-doors and turned up the volume on their radio to listen to the tunes from the Eurovision competition.” Krook “slipped inside” (where the radio was) and “pulled the plug.” Her “not-so-forgiving neighbors filed a complaint with the police”—so much for dancing cheek-to-cheek, to say nothing of turning the other cheek!

From New Zealand we learn that “you really should love thy neighbour, but you do not have to put up with the ‘excessive noise’ caused by the fluttering and slapping of his New Zealand flag.” If the appeal to patriotism doesn’t work any better than music, perhaps religion can provide an environment more conducive to love: “Love thy neighbor hasn’t been an easy commandment to follow for residents of the California hometown of the world’s largest televised ministry, Trinity Broadcasting Network.” There “bright lights, booming music, and flocks of tour buses at the headquarters, which resembles Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, have vexed neighbors.” A Trinity spokesperson declared, “Loving your neighbor as yourself is the essence of being a Christ-like person,” but such friction between the Network and its neighbors hardly seems in accord with the message of “the prince of peace.”

What’s the world coming to? “Cherie Woolls barricaded her neighbours onto their land with a hastily-built wooden fence”; two “Lincoln neighbours fought to the death over a privet and Leylandii hedge”; and a painter-decorator “shattered the peace in the village of Talybonton-Usk” when he killed a next-door neighbor over a wedding. These are but three examples of things gone terribly wrong, as reported in a story with the headline “Love Thy Neighbour? You Must Be Joking”—but these incidents sure don’t seem like jokes to me.

Sometimes, the problem is with the meaning of “love,” as when “an Aberdeen man took love thy neighbour a little too far when he kissed the man next door on the lips—which happened during a mock wrestling match.” John McConnell suffered something far more serious “when his wife of 11 years told him, ‘I’m leaving you’ and walked out with their kids … She had started living with the bloke who lives just three doors away. He said, ‘I’ve heard of love thy neighbour but this is awful. It’s torture having them so close by.’”

Indeed, it is narratives of just this sort that have led to developments on two related fronts. On the one hand, a British insurance concern has determined that “more than one in 10 people of those who had a neighbour dispute have consulted their solicitor.” On the other hand (or perhaps it’s just another finger on the same hand), a reality show with the title “Love Thy Neighbor” was planned: The show’s creators were “looking for people whose neighbors are as annoying as a paper cut.” They have reportedly narrowed their search to the states of Tennessee and Ohio.

To promote a far more irenic way of life, we happily note a Love Thy Neighbor effort—a “cooking program that teaches a trade to homeless people”—in Fort Lauderdale, Florida; a Love Thy Neighbor after-school program in Southeast Washington, D.C.; and a Love Thy Neighbor campaign, sponsored by the Pennsylvania Department of Health “to encourage African-Americans to Quit Smoking.” Food, education, better health—who could ask for anything more?

Well, perhaps David and Jo Beckett, whose trip to the altar is narrated in a story with the headline, “They Say, ‘Love Thy Neighbour’ … And So We Did! Couple Find Path to Romance Over the Garden Fence.”

Ah, for the civilities of the good old days! In a letter headed “What Happened to Love Thy Neighbour?” a correspondent writes in the Scottish Daily Record: “I was born in Knightswood, Glasgow, in 1930, and have lived there all my life … It’s so sad people don’t seem to care nowadays. A wee knock on the door doesn’t cost a thing.” The name and address of this individual are not provided. Could it be that, in today’s “neighborly” environment, he fears he might receive something decidedly less friendly than “a wee knock on the door”? I, for one, surely hope not.