Best of the Best: BR Articles Honored

We are pleased to recognize two outstanding scholars for their contributions to BR. Thanks to the generous support of the Leopold and Clara M. Fellner Charitable Foundation, through its trustee Frederick L. Simmons, we are able to honor the best articles that have appeared in these pages during 1996 and 1997.

This year’s judges, Susan Ackerman of Dartmouth College and James D. Tabor of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, independently chose the same articles for first place and honorable mention. Ackerman and Tabor based their selections on clarity of the writing, the originality of the authors’ interpretation and the the articles’ potential for advancing debate in Bible scholarship.

First Prize: Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, “Why Jesus Went Back to Galilee,” BR 12:01

According to the judges, this article, which explores the relationship of Jesus to John the Baptist, is everything a BR article should be: It offers a lucid and insightful presentation of up-to-date, cutting-edge research. It makes an important contribution to some of the larger debates currently at the center of New Testament scholarship, including the use of the Gospels as sources in the search for the historical Jesus, the eschatological dimensions of Jesus’ message, and the relationship of the Jesus movement to other major religious movements of first-century C.E. Palestine. Murphy-O’Connor, professor of New Testament at the École Biblique et Archéologique in Jerusalem, leads readers easily into the texts, inviting them to read critically, recognize the problems and consider a fascinating proposal.

Honorable Mention: Thomas Schmidt, “Jesus’ Triumphal March to Crucifixion: The Sacred Way as Roman Procession,” BR 13:01

The judges praised this article for its highly original and intriguing understanding of the passion narrative in Mark. The article argues that Mark deliberately shaped his crucifixion account so that it paralleled the triumphal marches of victorious generals and emperors parading through Rome. Schmidt, professor of New Testament at Westmont College in California, provides a model for scholars who seek to understand early Christianity within its larger social and political context.

American Bible Society Raises Its Profile

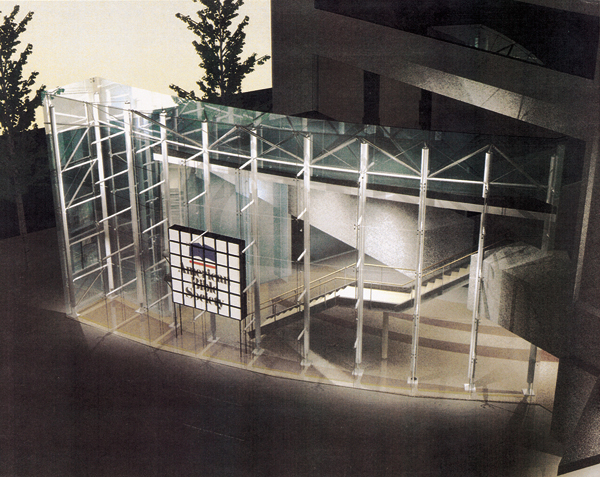

When the American Bible Society (ABS) renovated its headquarters near Lincoln Center in New York City, it decided it needed to expand its public profile at the same time. The result is a new gallery designed for museum-quality exhibits relating to the Judeo-Christian tradition, an expanded bookstore and a more accessible rare books library.

Since its founding in 1816, the ABS has aimed to publish inexpensive translations of the Bible with no doctrinal notes or comments. It is currently involved in 600 translation projects and has produced versions of the Bible in more than five dozen languages. But the ABS offices themselves have never made much of an impression on New York’s cultural landscape. “Our goal is to make ABS more open and outgoing with the new facilities, and especially with the new gallery,” according to Eugene B. Habecker, president of the ABS. “We wanted to make the gallery at the American Bible Society a destination for anyone interested in art and the Bible.”

Anne Edgar, a spokesperson for the ABS, told BR: “The whole idea was to bring to New York a scholarly exhibition that normally wouldn’t be here. There’s always going to be a display case with rare Scriptures from our collection on view.” The free gallery exhibitions will run year round.

Currently, a selection of rare and seldom-seen Scriptures from the ABS’s permanent collection is on display in an exhibit titled The American Bible Society: A History. This selection includes Scriptures the ABS has published and 15th- to 20th-century Bibles the organization has collected, according to librarian Mary Jane Ballou.

The ABS library, which dates from 1817, one year after the society was established, was created as a depository for ABS publications but has since become the largest collection of Scriptures and Scripture-related materials—over 53,000 volumes—in the Western hemisphere. “Over 2,000 languages now have at least one complete book of the Bible, and we collect all of them,” Ballou told BR.

The ABS’s rare books room includes the first Bible printed in America, called the Massachusetts Bible, written in the Algonquin language by missionaries in 1663. Other texts include a 15th-century Torah scroll from the Kaifeng Jewish community in China and a rare copy of Martin Luther’s 1522 German Bible. More than 1,200 of the library’s books are pre-1700 imprints.

The library is open by appointment only and welcomes scholars working in biblical studies and on the history of printing and publishing. Tours may be arranged for school and church groups. Call (212) 408–1236 or write to ABS, 1865 Broadway, New York, NY 10023; e-mail: gallery@americanbible.org.

Don’t Mess with This Curse

Not even the “Thou Shalt Not Steal” signs could curb theft at Pendlebury’s Bookshop, in North London. The shop specializes in secondhand religious books, but each year saw the disappearance of entire shelves worth of books.

So owner John Pendlebury put a curse on the thieves: “For him that stealeth a Book from this Library, let it change into a serpent in his hand and rend him. Let him be struck with Palsy, and all his Members blasted. Let him languish in Pain crying aloud for Mercy and let there be no surcease to his Agony till he sink in Dissolution. Let Bookworms gnaw his Entrails in token of the Worm that dieth not, and when at last he goeth to his final Punishment, let the flames of Hell consume him for ever and aye.” The 16th-century Spanish curse, posted inside the door, is the last thing customers see as they leave Pendlebury’s.

The curse apparently worked: Not only has theft virtually disappeared since Pendlebury posted the sign, but two anonymous customers have even sent back large boxes of stolen books.

Shoplifting seems to be a particular problem with religious titles (See “Thou Shalt Not Steal (Bibles)” in Jots & Tittles, BR 13:05). Pendlebury himself caught an Anglican priest and a rabbi stealing books from the psalm section of his shop on the same day. (Most of the shop’s customers are clerics of one persuasion or another, Pendlebury says.) Before posting the high-voltage curse, Pendlebury tried using surveillance cameras and confronting—and embarrassing—the thieves in his store, all to little avail. A customer acquainted with Pendlebury’s problem found the curse at the monastery of San Pedro in Barcelona.

“He saw the curse in the monastery’s library and immediately thought of me,” Pendlebury says.

Was Jesus Embalmed?

The Gospel of John gives what seems to be a straightforward account of Jesus’ burial: “Nicodemus, who had at first come to Jesus by night, also came, bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, weighing about a hundred pounds. They took the body of Jesus and wrapped it with the spices in linen cloths, according to the burial custom of the Jews” (John 19:39–40).

But these simple sentences suddenly lose some of their clarity if you turn to a Bible dictionary to find out more about myrrh and aloe.

The problem is that two different words are translated as myrrh and, although only one word is translated as aloe, that name is applied to two different plants.

Harper’s Bible Dictionary says “aloe” really means “eaglewood,” a plant native to India and used as perfume. The Revell Bible Dictionary says it may be the same bitter aloe referred to in the Old Testament.

Myrrh could be the spice called “

Embalming itself is another point of controversy among the dictionaries. Many, including the scholarly Anchor Bible Dictionary, assume that if the Egyptians used aloe and myrrh to embalm bodies, and if Nicodemus used them on Jesus, then he must have been trying to embalm Jesus’ corpse.

A strong argument can be made against the embalming theory. BR reader John B. Heczko, M.D., of South Pasadena, California, points out that in Jesus’ time tombs were used for multiple burials. Corpses were left to decay on a rock-cut bench in a family tomb. When the flesh had decayed, the bones were collected in stone boxes, called ossuaries, to make room for new bodies. That wouldn’t be possible if bodies were embalmed.

So why use aloe and myrrh? Say one family member died within a few months of another and a bench in the family tomb was needed before the first corpse had completely decomposed. That could make the atmosphere surrounding the later burial service very unpleasant. The only point on which everyone agrees regarding aloe and myrrh is that they were both commonly used as perfumes. And it would make sense to use such perfumes in burials. As Dr. Heczko puts it, “Wrapping a body in sweet-smelling spices spares the deceased the indignity of fouling the air of the tomb with the stench of his decomposing flesh.”

www.addendum

Since the article on finding the Bible on-line appeared in the June issue of BR (see Jots & Tittles), we’ve received several suggestions about more Web sites of biblical interest. Reader Robert C. Tompkins recommends the ARTFL Project site (http://estragon.uchicago.edu/Bibles/), which provides searchable texts in English, Latin, French and German. And, he says, the University of Michigan provides a searchable King James Bible, complete with Apocrypha, at (www.hti.umich.edu/relig/kjv/).