How does Moses make his coffee? Hebrews it. What kind of man was Boaz before he was married? Ruthless. Bible puns are like pineapple on pizza: Some people love them, and some people find them absolutely abhorrent.

The Bible itself is full of various kinds of wordplays, including puns, but they functioned quite differently than puns function in our modern culture. Rather than inducing groans, wordplay in biblical literature often functioned to mark structure in a poem, link two concepts, emphasize a central idea, or highlight irony or dissonance.

There are two broad categories of wordplay in the Hebrew Bible: those that play with meaning (polysemy) and those that play with sound (paranomasia). Of the wordplays that play with meaning, an author could use a word once with an implicit double meaning (double entendre, like the puns above) or the author could use punning repetition, where the word is repeated with a different meaning.

Wordplays that play with sound are more common in the Hebrew Bible and include alliteration (repetition of consonants), assonance (repetition of vowel sounds), parasonancy (the change of only one root letter), letter transposition (the order of the root letters changes), and more.

But how does a literary device that is so tied to the original language of a text translate to other languages? Is it even possible? Consider the following line from Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven”: “While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping.” We could translate this line into any language and maintain the sense (the meaning) of the line, but if we cannot communicate the style as well, have we succeeded as translators?

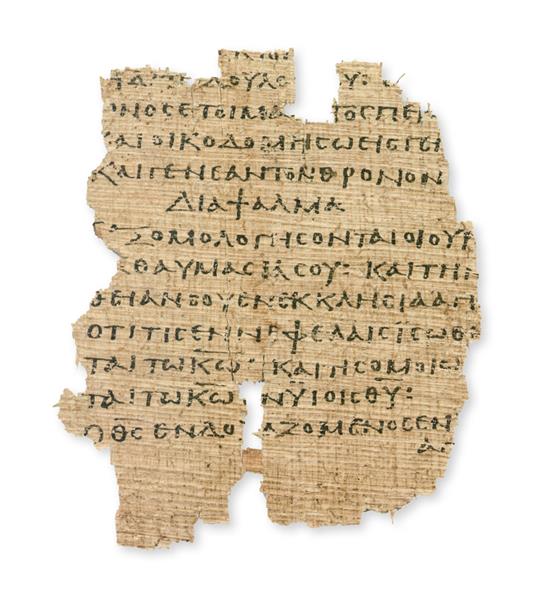

The Greek translators of the Hebrew Bible seemed to have felt that same tension between wanting to accurately translate both the sense and the style of the original Hebrew. The Septuagint was the first translation of the Hebrew Bible, with sections of translations dating back as far as the third century B.C. The completion of the Septuagint by the first century A.D. is confirmed by the fact that the New Testament authors quoted from the Septuagint translation more often than the Hebrew text.a

The Septuagint translators seemed to approach wordplay in three ways. (1) If possible, they would replicate the same wordplay by using the same terms and the same type of wordplay. (2) More commonly, they would represent the original wordplay by using different (but adjacent) terms or by using a different kind of wordplay. (3) If rendering the wordplay proved too challenging, they would render the sense of the original, but not the wordplay.

To put some data with these descriptions, we can consider Book 4 of Psalms (Psalms 90-106), where the translators were able to render roughly a third of the original wordplays. Moreover, the vast majority of wordplay in the Septuagint corresponds with the Hebrew wordplay (about 85 percent of the total Greek wordplay), making coincidental overlap or “false positives” unlikely.1

The following examples illustrate their technique and deliberations to best account for the sense and style of the original.

In Psalm 101:3, the Hebrew poet uses alliteration to demarcate the line and emphasize his or her attitude toward transgressors:

‘esoh-setim saneti

The work of transgressors I hate

The Septuagint translator was able to use alliteration with two of these terms as well as four additional terms in the preceding line:

ou proethēm pro ophthalmōn mou pragma paranomon

I have not set before my eyes an unlawful thing

polountas parabaseis emisēsa

Those who commit transgressions I have hated

Some alliteration might be inevitable or incidental, but several factors suggest that both the Hebrew poet and the Greek translator used alliteration intentionally. The Hebrew poet’s choice of ‘esoh for “I hate” is a hapax legemenon, meaning that it occurs only this one time in the entire Hebrew Bible. Since there are, as you might imagine, many other more common words with the sense “to hate,” the poet’s choice here seems to come from a desire to play with the “s” sounds.

The Septuagint translators also show deliberateness in their alliteration. The word for “transgressions” (parabaseis) is also a hapax legomenon, and the words paranomon and poiountas are not standard translation equivalents for “unlawful” and “those who commit.” In other words, the translators break from their typical style and word choices to create this sevenfold alliteration.

The translators sometimes made subtle changes, or transformations, to replicate or represent the original wordplay. Such changes occur in nearly half (48 percent) of Psalms 90-106. In Psalm 104:12, the Hebrew poet plays on the words for “birds” (‘oph) and their dwelling place (‘ophayim, “foliage”):

‘alehem ‘oph-hashamaim yishekon

With them the birds of the heavens dwell

miben ‘ophayim yitenu-qol

From among the foliage they lift up a voice

The repetition of the “oph” sounds, in the same place in their respective lines, coupled with the rarity of the word for foliage (‘ophayim), when many other words for plants were at the poet’s disposal, all mark this as a genuine wordplay.

The Greek translator plays on the same words, but must sacrifice the sense of the second word. Instead of the birds dwelling in the foliage, the Greek translator describes them dwelling in the rocks, thus maintaining the alliteration between the two words:

ep auta ta peteina tou ouranou kataskēnōsei

Among them the birds of the heaven dwell

ek mesou tōn petrōn dōsousin phōnēn

From the midst of the rocks they lift up a voice

It is possible that the Greek translators did not recognize the rare Hebrew word for “foliage” and so guessed at a translation equivalent. However, if that were the case, we might expect a better guess, especially since just a few verses later the psalmist explicitly describes the homes of birds to be cedars and firs (Psalm 104:16-17), whereas small ground animals prefer the rocks (Psalm 104:18). In all three of those cases, the Septuagint uses the expected translation equivalents. Therefore, the choice of petrōn (“rocks”) for ‘ophayim (“foliage”) seems to be motivated by a desire to render the Hebrew wordplay in an effective way that would not change the meaning of the Hebrew in any significant way. In other words, it was an easy sacrifice and apparently one outvalued by the benefit of rendering the style of the Hebrew poet.

The Septuagint translators did a remarkable job of both recognizing and representing Hebrew wordplays, and the difficult choices they had to make between style and sense are some of the same challenges that modern translators of the Bible face. Surely, that should give us some inspiration today. What’s that? Don’t call you “Shirley”? (See what I did there?)

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. See, e.g., Harvey Minkoff, “Problems of Translation,” Bible Review, August 1988.