Origins: A Codex Moment

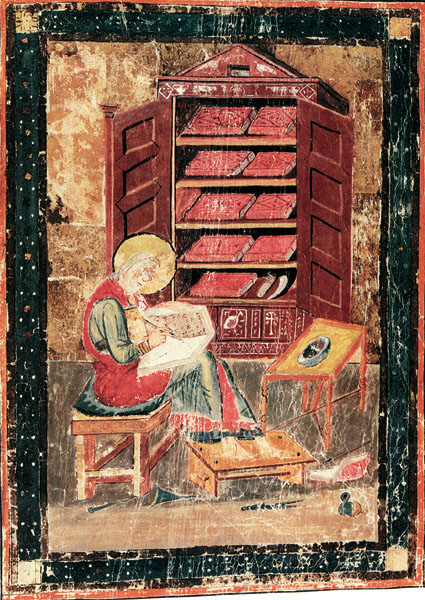

2,000 years ago, a new writing surface and a renegade religion joined forces to create the modern book.

006

My 15-month-old daughter, Delia, is mastering language at a frightening rate. She understands the word “two,” and when our dogs bark, she looks up and says “mailman.” She also uses language to categorize objects: “Duck,” for instance, refers to anything resembling a bird, and “choo-choo” refers to all large vehicles and to the laundry baskets we sometimes use as wagons.

Delia has recently learned the word “book,” and like most of us, she uses it to designate any materials that appear in the form of a codex (a collection of leaves or pages bound at one side). Such bound volumes have come to represent everyone’s image of a book. But codices were not, and are not, the only form a text can take.

In the 18th century B.C., Hammurabi’s law code was inscribed on a 7-foot-high chunk of basalt. More than a thousand years earlier, the Sumerians were keeping financial records on clay tablets and inscribing text on small seals made of seashell or gemstones.

For lengthy, portable documents, however, another medium was needed. The Torah, an integral part of any synagogue, reminds us that when the ancients referred to a book, they usually meant a scroll. Scrolls were made of several materials: Some that survived are cured animal skins; a tiny seventh-century B.C. scroll (one and a half inches long and a half inch wide), found in a tomb in Jerusalem and inscribed with text from the “Priestly Blessing” (Numbers 6:24–26), is made of silver; and one of the Dead Sea Scrolls is copper.

The material preferred by ancient Egyptians and Greeks was papyrus, a tall marsh plant that grows abundantly in the Nile Valley. Sheets were made by placing layers of papyrus strips at right angles to one another and then pounding or pressing them flat; the sap would then bind the strips together. Rolls were formed by attaching papyrus sheets end to end. Ancient scribes generally wrote in columns parallel to the short side of the scroll rather than down the entire length of the scroll (which could be 30 feet long for a Greek roll and three times that for an Egyptian papyrus). The 007reader would peruse the text by unrolling one end of the scroll and rolling up the other.

Versions of the codex may have been used by the Mesopotamians early in the second millennium B.C. (see “Recovered! The World’s Oldest Book”). These early codices were wood, clay or ivory writing tablets, with two or more leaves joined by hinges or leather thongs. Many of the writing tablets had hollowed-out surfaces that were coated with wax and marked up with a stylus; the surface could then be smoothed over so that new text could be inscribed. These multi-leaved wax tablets were suited only for short writings, such as private letters or inventory lists.

Two things combined to facilitate the western world’s transition from the scroll to the kind of codex that, today, we call a book: the development of parchment as a viable alternative to papyrus, and the rise of Christianity.

According to the first-century A.D. Roman historian Pliny the Elder, parchment came into use as a result of competition between Ptolemy V (210–180 B.C.) of Egypt and Eumenes II (197–159 B.C.) of Pergamum, in western Anatolia. Seeking to maintain the Alexandria Library’s preeminence in the ancient world, Ptolemy banned the export of papyrus to be used at the library of Pergamum, forcing Eumenes to develop a new writing material. Whether or not the story is true, Pergamum was an important exporter of parchment (the word “parchment” derives from the name “Pergamum”), and the story recognized an important developing competition between the two writing surfaces.

Parchment had several advantages over papyrus. It was available wherever there were sheep, goats or cattle. It was more durable than papyrus, which the Greeks complained lasted only two or three centuries (some ancient Egyptian papyri have survived because of the dry Egyptian climate, not because of the strength of the material). Parchment could be scraped clean and reused—creating a palimpsest—more successfully than papyrus. And parchment could be folded, quired (one sheet stuffed inside another, like this copy of Archaeology Odyssey) and bound. Papyrus, which was also used in codices for several centuries, was weakened by folding and sewing.

The codex form itself provided distinct benefits. The leaves of codices, whatever material they were made of, could be inscribed on both sides, whereas scrolls were generally written on only one side. Even more importantly, codices could be referred to more easily than scrolls. To find a passage in a scroll, the reader needed to unroll the document to reach the proper citation; with a codex, one needed only to turn pages. Finally, codices were simply easier to carry around and read. The first-century A.D. Roman poet Martial praised parchment codices in his Epigrams: “You, who wish my poems should be everywhere with you, and look to have them as companions on a long journey, buy these which the parchment confines in small pages. Assign your book-boxes to the great; this copy of me one hand can grasp.”

Despite Martial’s praise, the ancient Romans must not have had a pressing need for the parchment codex. Wall paintings and library caches from Pompeii and Herculaneum show that the Romans continued to use scrolls in the first century A.D. Early Christians, however, needed everything a parchment or papyrus codex could provide. The codex’s size, portability and ease of reference—together with the fact that it was not yet associated with the major texts of pagan writers—made the form ideal for an underground religion based on a written text. The bibliographer Leila Avrin has pointed out that all extant Christian works from second-century A.D. Egypt are codices, whereas only two percent of the surviving non-Christian manuscripts are codical in form.a Indeed, many of the oldest and best-preserved parchment codices, such as the early fourth-century Codex Sinaiticus, found at St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai, and the mid-fourth-century Codex Vaticanus in the Vatican Library, contain early editions of the New Testament.

As Christianity spread, so did the codex. By the time Constantine the Great granted Christians complete religious freedom in 313, the codex had essentially replaced the scroll except in certain official functions. The dominance of papyrus as a writing material faded along with the scroll, although more slowly. The fourth-century Gnostic Gospels found in Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in 1945, for instance, are papyrus codices. But in the end, the more flexible, durable parchment codex won the day.

Clearly, we have not completely abandoned the rolled book. Many large books and most magazines are printed in columns, a format that harkens back to ancient rolls. And when we need to see the next block of information on our computers, we don’t turn the pages, we “scroll” down. But still, when we think of a book, we think of a codex. Delia knows this. Seeing a roll of paper, she doesn’t compare it to her copy of Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You? She holds it to her lips and yells “Toot, toot!”

My 5-month-old daughter, Delia, is mastering language at a frightening rate. She understands the word “two,” and when our dogs bark, she looks up and says “mailman.” She also uses language to categorize objects: “Duck,” for instance, refers to anything resembling a bird, and “choo-choo” refers to all large vehicles and to the laundry baskets we sometimes use as wagons. Delia has recently learned the word “book,” and like most of us, she uses it to designate any materials that appear in the form of a codex (a collection of leaves or pages bound at one side). Such bound […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.