Origins: Let the Games Begin!

We human beings like to think of ourselves as wise, as homo sapiens. But we share two of our most common qualities with the beasts. We are often murderous, and hence have been described as homo necans in a disquisition on violence (in relation to Greek sacrificial rites and myths) published under that title by Walter Burkert. And we are irrepressibly playful, as documented in Jan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens.

Evidence of this universal playfulness goes deep into the past. Surprisingly, some of its manifestations have stayed recognizably similar over the millennia, such as dice and board games.

It may seem odd that so specific a phenomenon as dice should have its origin in antiquity, and yet that is true not only of the concept but of the precise form. The earliest dice known date to the second half of the third millennium B.C.E.; they come from the Indus Valley culture, in present-day Pakistan, and from Mesopotamia in the Early Dynastic III period (c. 2500–2300 B.C.E.). These ancient specimens look very much like modern dice, and some of them have dots arranged in the modern way (with dots on opposite sides adding up to seven). The Mesopotamians continued to play with dice in the second and first millennia B.C.E.; a late example from Babylon is even made of glass. Further west, in Palestine and Egypt, various shapes were experimented with, but the “modern” cubical shape and dot arrangement is also attested, for example in dice recovered in excavations at Ashkelon.

Some dice have been found in association with board games, which also have a hoary antiquity. The classic study of board games is a Latin treatise by the British orientalist Thomas Hyde (1636–1703), who also introduced the term dactyli cuneiformes, or cuneiform signs. Hyde’s De Ludis Orientalibus was translated as Chess: Its Origin by Victor Keats (1995), who also gave us books on Chess, Jews and History (1994) and Chess Among the Jews (1995). But for all its fabled past in India or the Persian Near East, and its subsequent conquest of the world, chess is a relative newcomer on the scene. Checkers, too, which also uses a board of 64 squares, probably only goes back to Egyptian forerunners in the late second millennium B.C.E.

But there are far older board games, basically of three types.

The simplest is a board with 58 holes arranged in four lines, with the two outside lines having 19 holes each and the two inside lines having 10 holes each. This game required counters to be moved from hole to hole according to certain rules. The counters, and the dice associated with the game, would have been pebbles or the knucklebones of sheep or other small animals (sometimes called astragali, from the Greek word astragaloi). The game board itself, though sometimes made of wood, ivory or even stone, was typically made of clay. This game has been played all over the Near East, from ancient times down to the present day.

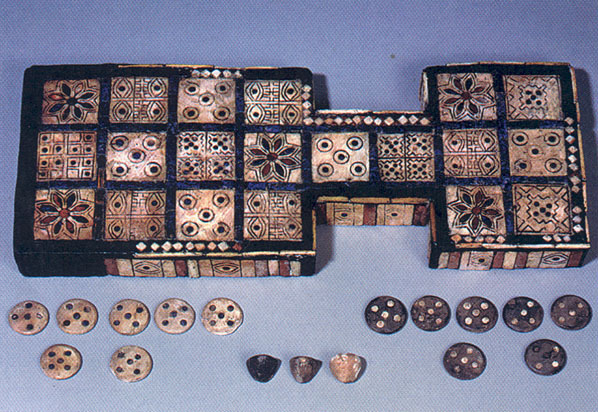

A more sophisticated game board was found in the excavations of the Royal Graves at Ur, dating to the middle of the third millennium B.C.E. Elaborately carved and inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli (see photo, above), the board has 20 squares in seven different patterns. Variations on these 20-square game boards have been found at ancient Assyrian sites, in modern Lebanon (Kumidi), in the Indus Valley and at Shahr-I-Sokhta in northeastern Iran, the last in the form of a snake. This snake-shaped board from Iran suggests a connection with the senet game of Egypt, which has 20 to 30 squares typically arranged in the shape of a snake.

The most complicated ancient game board is represented by only two Mesopotamian examples. This board is divided into 84 fields by horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines. The inscription on one of the boards is probably the name of the game:

That playfulness is a universal trait is not surprising. What is impressive, however, is that devices created to satisfy this craving have survived in similar form over such an extraordinarily long period of time and across so much of the world.

We human beings like to think of ourselves as wise, as homo sapiens. But we share two of our most common qualities with the beasts. We are often murderous, and hence have been described as homo necans in a disquisition on violence (in relation to Greek sacrificial rites and myths) published under that title by Walter Burkert. And we are irrepressibly playful, as documented in Jan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens. Evidence of this universal playfulness goes deep into the past. Surprisingly, some of its manifestations have stayed recognizably similar over the millennia, such as dice and board games. It may seem […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.