Articles in BAR often write “Yahweh” as the name of ancient Israel’s God. This concerns some readers, as occasionally expressed in letters to the editor (see Queries & Comments). Here, I explain why many—but not all—biblical scholars and archaeologists use this name. The problem involves two intertwined facts: (1) The letters of the tetragrammaton—YHWH—are not fully vocalized in the Hebrew Bible; and (2) Jewish tradition prohibits the pronunciation of this name. Why, then, do we say Yahweh if this pronunciation is both obscure and heretical? I first address the name’s obscure vocalization, and then the apparent heresy.1

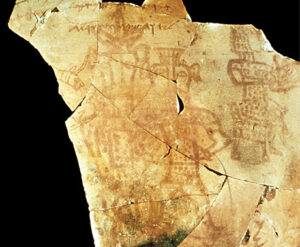

Ancient Hebrew is written consonantally, with some consonants used sometimes to indicate vowels. In the four letters of the tetragrammaton, the first three letters represent consonants, and the last letter (the final he) is a vowel marker. This is so in Iron Age inscriptions—for instance, in the Mesha Stele, the Kuntillet ‘Ajrud inscriptions, and letters from Arad and Lachish—and in the Hebrew Bible.

In the Bible, the consonantal writing is overlaid with vowel points inserted in medieval times, which preserve old reading traditions. The vowel points usually written under the letters YHWH are the vowels for the Hebrew word Adonai, “my Lord.” They are not the vowels for YHWH. Why is this so? Because the reading tradition preserves the custom that one does not pronounce the name of God, instead substituting the epithet “my Lord.” This customary substitution goes back to at least the third century BCE, when the Old Greek translation of the Pentateuch translated YHWH as “Lord” (kurios, in Greek) or copied the name in Hebrew letters. The point is that the reading tradition doesn’t preserve the original pronunciation of YHWH. So why do we think that Israelites and Jews in earlier periods pronounced it as Yahweh?

The answer is pretty straightforward. The vocalization of the first syllable is actually preserved, mostly in liturgical expressions and personal names. “Halleluyah,” a frequent refrain in the Psalms, means “Praise Yah.” Yah is a short form of God’s name, as it is in Exodus 15:2, “Yah is my strength and my might.” The same short form is found in many personal names, such as Obadiah (“servant of Yah”) and in the names of many well-known biblical figures, including Isaiah, Jeremiah, Josiah, Micaiah, Zedekiah, Zechariah, and Nehemiah. This is obvious evidence for the ancient pronunciation of the first syllable of the name of YHWH as Yah.

The pronunciation of the second syllable is relatively easy to sort out. The final he, the vowel marker, can indicate e, ō, or ā. Following the first syllable Yah, the only final vowel that makes linguistic sense is e. This is because a Hebrew word starting with ya- is inevitably a verb, for which a final he always indicates the vowel e. An example is the place-name Yavneh, which derives from the verb yabneh, “he builds.” This verb was originally yabniyu in pre-Hebrew dialects and contracted to yabneh (with final he indicating the e). The history of the divine name Yahweh probably follows the same pattern, with pre-Hebrew Yahwiyu contracting to Yahweh. The evidence of some later Greek transcriptions, Iabe and Iaoue, points to the same outcome.

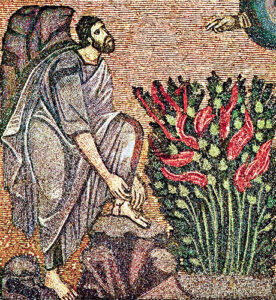

Yahweh might originally be a dynamic form of the verb “to be,” meaning something like “he moves, blows,” or it could be a causative form, meaning something like “he makes.” But the name’s meaning seems to have been forgotten in classical Hebrew. At Mt. Horeb, when Moses asks God to reveal his name, God says ’ehyeh ’ăšer ’ehyeh (“I am that I am,” or “I am he who continually exists”), which is a wordplay on the not-yet-revealed name Yahweh. Then God tells Moses that his true name is YHWH (remember, not fully vocalized in the consonantal text), concluding his speech with a touch of poetry: “This is my name forever; this is my designation for all generations” (Exodus 3:14–15). Notice that God’s name is both concealed and revealed in this scene. The name is hinted at with “I am” because ʾehyeh sounds like Yahweh.

The second part of the problem involves the prohibition of pronouncing the name Yahweh. Why was the word “Lord” (or other substitutions) used instead? This has to do with the interpretation of the third commandment, “You shall not take the name of YHWH your God in vain” (Exodus 20:7; cf. Deuteronomy 5:11). This seems to forbid invoking the name of YHWH in false oaths or other illicit speech. Cursing God is prohibited in Exodus 22:28 and is punished by death in Leviticus 24:15–16. Taking a false oath in God’s name is prohibited in Leviticus 19:12. Oaths generally used the phrase “as YHWH lives” (ḥay-yhwh), as when King Saul says, “As YHWH lives, no punishment will come to you for this thing” (1 Samuel 28:10). This is explained as “Saul swore to her by YHWH.” Originally, this commandment prohibited the misuse of God’s name. It had nothing to do with the pronunciation of the name itself.

Later interpretive tradition expanded the scope of this commandment to include any invocation of the name of YHWH. (The earliest evidence is the Old Greek translation of Leviticus 24:16, which gives the death penalty to “whoever names” the name of God, reinterpreting the Hebrew, “whoever curses.”) This follows the common tendency to “build a hedge around the Law.” If one never says the name of YHWH, then one can never take it in vain. This interpretive move means that other terminology must be used when saying God’s name or reading the name YHWH in the Bible. “Lord” or “my Lord” fit the bill nicely. Orthodox Jews often say “the Name” (ha-Shem) for the name of God, which is another way of not saying the name.

Why then do many scholars and archaeologists say Yahweh instead of Adonai (“my Lord”) as indicated in the vowel pointing, or ha-Shem (“the Name”) as do Orthodox Jews? This is because critical scholarship usually prefers language that is historical rather than devotional. It is our own signal that this is academic speech, not speech of the church or synagogue. I should add that some scholars do say Adonai or write YHWH without vowels out of respect for devotional practices, including the traditional Jewish interpretation of the third commandment. This is a matter of personal choice. But my point is, when a scholar writes Yahweh in BAR or elsewhere, this is a historical claim, not a devotional one. It is not meant with any disrespect or hint of heresy. We simply think that this is the name as it was said in ancient Israel, by speakers of classical Hebrew and the writers of the Bible.

Editor’s note: Ronald Hendel serves on BAR’s Editorial Advisory Board.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

1. For fuller discussion of the linguistic issues, see Theodore J. Lewis, The Origin and Character of God: Ancient Israelite Religion through the Lens of Divinity (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2020), pp. 210–252.