Past Perfect: Excavating Nimrud

Austen Henry Layard describes the journey of two colossal statues from a buried Assyrian palace to the British Museum.

042

Many of the 19th century’s most significant archaeological discoveries were made by men who recorded their adventures for the general public. In this issue, Past Perfect presents one such narrative: Austen Layard’s dramatic account of the removal of a winged bull from Nimrud.

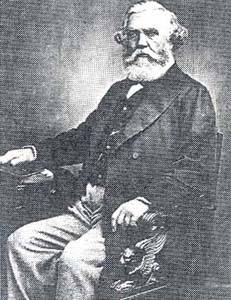

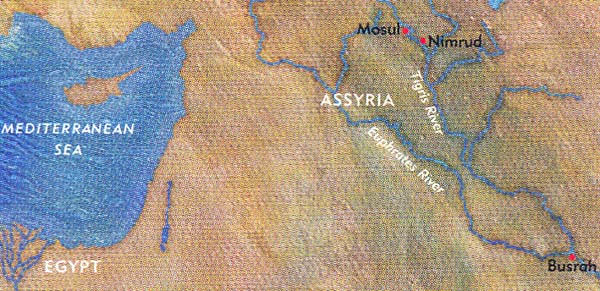

In the early, swaggering days of European archaeology, excavators were often adventurers, tunneling through mounds and ruins, in pursuit of ancient treasures. At the age of 22, the Englishman Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894) set off for the East in search of exotica; in the end, he helped develop the fledgling field of Assyriology. Layard began digging at Nimrud, located on the east bank of the Tigris River in modern-day Iraq, in November 1845 and immediately discovered portions of two Neo-Assyrian palaces, including one of King Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 B.C.). By the time he left Mesopotamia, two years later, he had uncovered the remains of six more palaces and supplied the British Museum with a treasure trove of Assyrian artifacts—including the celebrated Black Obelisk, a stone stela nearly seven feet tall covered with reliefs and cuneiform inscriptions. In 1849, Layard published Nineveh and Its Remains, a lively account of his excavations. Because of Layard’s engaging prose style and gift for narrative drama, the book became wildly popular, propelling Near Eastern archaeology to the forefront of the popular imagination. One particularly riveting passage describes Layard’s removal of two massive statues, a winged bull and a winged lion, from Ashurnasirpal’s palace. Carefully loaded onto rafts, the colossi floated down the Tigris River, through the Persian Gulf and into the Arabian Sea—destined eventually for London’s British Museum. —Ed.

043

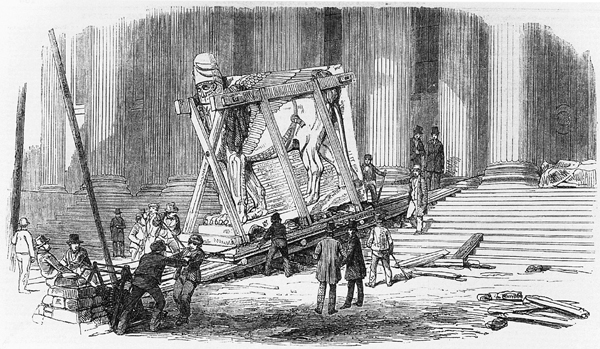

The Trustees of the British Museum had not contemplated the removal of either a winged bull or lion, and I had at first believed that, with the means at my disposal, it would have been useless to attempt it. They wisely determined that these sculptures should not be sawn into pieces, to be put together again in Europe They were to remain, where discovered, until some favourable opportunity of moving them entire might occur; and I was directed to heap earth over them, after the excavations had been brought to an end. Being loath, however, to leave all these fine specimens of Assyrian sculpture behind me, I resolved upon attempting the removal and embarkation of two of the smallest and best preserved

I formed various plans for lowering the smaller lion and bull, for dragging them to the river, and for placing them upon rafts At last I resolved upon constructing a cart sufficiently strong to bear any of the masses to be moved. As no wood but poplar could be procured in the town, a carpenter was sent to the mountains with directions to fell the largest mulberry tree, or any tree of equally compact grain, he could find; and to bring beams of it, and thick slices from the truck, to Mosul [northwest of Nimrud, on the other side of the Tigris River].

By the month of March [1847] this wood was ready Each wheel was formed of three solid pieces, nearly a foot thick, from the trunk of a mulberry tree, bound together by iron hoops. Across the axles were laid three beams, and above them several cross-beams, all of the same wood. A pole was fixed to one axle, to which were also attached iron rings for ropes, to enable men, as well as buffaloes, to draw the cart. The wheels 044were provided with moveable hooks for the same purpose

The bull was ready to be moved by the 18th of March. The earth had been taken from under it, and it was now only supported by beams resting against the opposite wall. Amongst the wood obtained from the mountains were several thick rollers. These were placed upon sleepers or half beams, formed out of the trunks of poplar trees, well greased and laid on the ground parallel to the sculpture. The bull was to be lowered upon these rollers. A deep trench had been cut behind the second bull, completely across the wall. A bundle of ropes coiled round this isolated mass of earth served to hold two blocks, two others being attached to ropes wound round the bull to be moved. The ropes, by which the sculpture was to be lowered, were passed through these blocks; the ends, or falls of the tackle, as they are technically called, being led from the blocks above the second bull, and held by the Arabs. The cable having been first passed through the trench, and then round the sculpture, the ends were given to two bodies of men. Several of the strongest Chaldeans [a Semitic-speaking people of Mesopotamia by which Layard referred to the local Arabs] placed thick beams against the back of the bull, and were directed to withdraw them gradually, supporting the weight of the slab and checking it in its descent, in case the ropes should give way

The men being ready, and all my preparations complete, I stationed myself on the top of the high bank of earth over the second bull, and ordered the wedges to be struck out from under the sculpture to be moved. Still, however, it remained firmly in its place. A rope having been passed round it, six or seven men easily tilted it over. The thick, ill-made cable stretched with the strain, and almost buried itself in the earth round which it was coiled. The ropes held well. The mass descended gradually, the Chaldeans propping it up with the beams. It was a moment of great anxiety. The drums and shrill pipes of the Kurdish musicians increased the din and confusion caused by the war-cry of the Arabs, who were half frantic with excitement. They had thrown off nearly all their garments; their long hair floated in the wind; and they indulged in the wildest postures and gesticulations as they clung to the ropes. The women had congregated on the sides of the trenches, and by their incessant screams added to the enthusiasm of the men Away went the bull, steady enough as long as supported by the props behind; but as it came nearer to the rollers, the beams could no longer be used. The cable and ropes stretched more and more. Dry from the climate, as they felt the strain, they creaked and threw out dust. Water was thrown over them, but in vain, for they all broke together when the sculpture was within four or five feet of the rollers. The bull was precipitated to the ground. Those who held the ropes, thus suddenly released, followed its example, and were rolling, one over the other, in the dust. A sudden silence succeeded to the clamour. I rushed into the trenches, prepared to find the bull in many pieces. It would be difficult to describe my satisfaction, when I saw it lying precisely where I had wished to place it, and uninjured! The Arabs no sooner got on their legs again, than, seeing the result of the accident, they darted out of the trenches, and, seizing by the hands the women who were looking on, formed a large circle, and, yelling their war-cry with redoubled energy, commenced a most mad dance

I now prepared to move the bull into the long trench which led to the edge of the mound. The rollers were in good order; and, as soon as the excitement of the Arabs had sufficiently abated to enable them to resume work, the sculpture was dragged out of its place by ropes.

Sleepers were laid to the end of the trench, and fresh rollers were placed under the 046bull as it was pulled forwards by cables. The sun was going down as these preparations were completed. I deferred any further labour to the morrow. The Arabs dressed themselves; and, placing the musicians at their head, marched towards the village, singing their war songs, and occasionally raising a wild yell, throwing their lances into the air, and flourishing their swords and shields over their heads

After passing the night in this fashion, these extraordinary beings, still singing and capering, started for the mound. Everything had been prepared on the previous day for moving the bull, and the men had now only to haul on the ropes. As the sculpture advanced, the rollers left behind were removed to the front, and thus in a short time it reached the end of the trench. There was little difficulty in dragging it down the precipitous side of the mound. When it arrived within three or four feet of the bottom, sufficient earth was removed from beneath it to admit the cart, upon which the bull itself was then lowered by still further digging away the soil. It was soon ready to be dragged to the river

On the 20th of April, there being fortunately a slight rise in the river, and the rafts being ready, I determined to attempt the embarkation of the lion and bull. The two sculptures had been so placed on beams that, by withdrawing wedges from under them, they would slide nearly into the centre of the raft. The high bank of the river had been cut away into a rapid slope to the water’s edge.

The beams of poplar wood, forming an inclined plane from beneath the sculptures to the rafts, were first well greased. A raft, supported by six hundred skins [taken from goats and sheep], having been brought to the river bank, opposite the bull, the wedges were removed from under the sculpture, which immediately slided down into its place. The only difficulty was to prevent its descending too rapidly, and bursting the skins by the sudden pressure. The Arabs checked it by ropes, and it was placed without any accident. The lion was then embarked in the same way, and with equal success, upon a second raft of the same size as the first; in a few hours the two sculptures were properly secured, and before night they were ready to float down the river to Busrah [see map, p. 44]. Many slabs, and about thirty cases containing small objects discovered in the ruins, were placed on the rafts with the lion and bull

I watched the rafts until they disappeared behind a projecting bank of the river. I could not forbear musing upon the strange destiny of their burdens; which, after adorning the palaces of the Assyrian kings, had been buried unknown for centuries beneath a soil trodden by Persians under Cyrus, by Greeks under Alexander, and by Arabs under the first successors of their prophet. They were now to visit India, to cross the most distant seas of the southern hemisphere, and to be finally placed in a British Museum. Who can venture to foretell how their strange career will end?

—From Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, (London: Murray, 1867).

Many of the 19th century’s most significant archaeological discoveries were made by men who recorded their adventures for the general public. In this issue, Past Perfect presents one such narrative: Austen Layard’s dramatic account of the removal of a winged bull from Nimrud. In the early, swaggering days of European archaeology, excavators were often adventurers, tunneling through mounds and ruins, in pursuit of ancient treasures. At the age of 22, the Englishman Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894) set off for the East in search of exotica; in the end, he helped develop the fledgling field of Assyriology. Layard began digging […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.