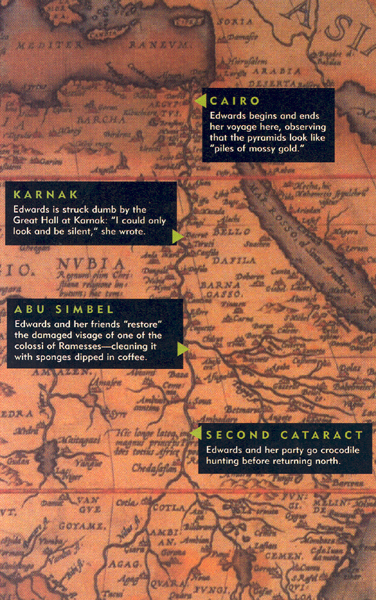

As a young woman, Amelia Edwards (1831–1892) won fame and fortune writing popular novels. She spent her twenties and thirties producing lurid, best-selling tales of romance, like the 1864 saga of bigamy, Barbara’s History. In the final decades of her life, however, this British author assumed a new identity—as an antiquarian. In 1873 Edwards was commissioned to write a travel guide to ancient Egypt. Joining a handful of British adventurers on a 1,000-mile odyssey up the Nile, she traveled from Cairo to the Nile’s Second Cataract in a dahabiyah (a small, flat-bottomed sailboat), visiting numerous archaeological sites along the way. As she roamed, Edwards found herself charmed by the strange habits of the Egyptian people, but outraged by their neglect of their ancient heritage. In 1874 she returned to England determined to save Egypt’s ancient monuments from decay. Immersing herself in the field of Egyptology, she began studying with some of the most famous archaeologists of her day. In 1882 she helped establish the Egypt Exploration Fund (now the Egypt Exploration Society). As the fund’s executive secretary, she spent the next decade traveling the globe and raising money for the excavation of sites such as Tell el-Amarna, where a hoard of cuneiform tablets was later found, and Memphis, capital of Egypt for most of the pharaonic period. When she died of influenza in 1892, Edwards left £5000 to the University College of London for the founding of a chair in Egyptology and Philology—a position she insisted be held by her friend Sir William Flinders Petrie (often regarded as the father of scientific archaeology in Palestine and Egypt). “I am the only Romanticist in the world,” Edwards once wrote with characteristic swagger, “who is also an Egyptologist.” Her remarkable ability to excite ordinary people’s interest in archaeology—to make even the most trivial of discoveries into a romantic adventure—is evident in the first book she wrote about her Egyptian travels, A Thousand Miles Up the Nile (1877). This excerpt—sometimes whimsical, sometimes scholarly, always entertaining—recounts an unexpected discovery at the Temple of Abu Simbel in southern Egypt.—Ed.

The day was Sunday; the date February 16th, 1874; the time, according to Philae reckoning, about eleven A.M., when the Painter [one of Amelia Edward’s unnamed traveling companions], enjoying his seventh day’s holiday after his own fashion, went strolling about among the rocks [at Abu Simbel] …

His attention was arrested by some much mutilated sculptures on the face of the rock, a few yards nearer the south buttress of the Temple. He had seen these sculptures before—so, indeed, had I, when wandering about that first day in search of a point of view—without especially remarking them.

The thing that now caught the Painter’s eye, however, was a long crack running transversely down the face of the rock. It was such a crack as might have been caused, one would say, by blasting.

He stooped—cleared the sand away a little with his hand—observed that the crack widened—poked in the point of his stick; and found that it penetrated to a depth of two or three feet. Even then, it seemed to him to stop, not because it encountered any obstacle, but because the crack was not wide enough to admit the thick end of the stick.

This surprised him. No mere fault in the natural rock, he thought, would go so deep. He scooped away a little more sand; and still the cleft widened. When he probed the cleft with it this second time, it went in freely up to where he held it in his hand—that is to say, to a depth of quite four feet.

Convinced now that there was some hidden cavity in the rock, he carefully examined the surface. There was yet visible a few hieroglyphic characters and part of two cartouches, as well as some battered outlines of what had once been figures …

They were the hands and arms, apparently, of four figures; two in the centre of the composition, and two at the extremities. The two centre ones, which seemed to be back to back, probably represented gods; the outer ones, worshippers.

All at once, it flashed upon the Painter that he had seen this kind of group many a time before—and generally over a doorway.

Meanwhile, the luncheon bell having rung thrice, we concluded that the Painter had rambled off somewhere into the desert; and so sat down without him. Towards the close of the meal, however, came a pencilled note, the contents of which ran as follows:

“Pray come immediately—I have found the entrance to a tomb. Please send some sandwiches—A. M’C.”

All that Sunday afternoon, heedless of possible sunstroke, unconscious of fatigue, we toiled upon our hands and knees, as for bare life, under the burning sun. We had all the crew up, working like tigers …

The opening grew rapidly larger. When we first came up—that is, when the Painter and the two sailors had been working on it for about an hour—we found a hole scarcely as large as one’s hand, through which it was just possible to catch a dim glimpse of painted walls within. By sunset, the top of the doorway was laid bare, and where the crack ended in a large triangular fracture, there was an aperture about a foot and a half square, into which Mehemet Ali [one of the party’s native guides] was the first to squeeze his way. We passed him in a candle and a box of matches; but he came out again directly, saying that it was a most beautiful Birbeh, and quite light within.

The Writer [Edwards herself] wriggled in next. She found herself looking down from the top of a sandslope into a small square chamber. This sand-drift, which here rose to within a foot and a half of the top of the doorway, was heaped to the ceiling in the corner behind the door, and thence sloped steeply down, completely covering the floor. There was light enough to see every detail distinctly—the painted frieze running round just under the ceiling; the bas-relief sculptures on the walls, gorgeous with unfaded colour …

Satisfied that the place was absolutely fresh and untouched, the Writer crawled out, and the others, one by one, crawled in. When each had seen it in turn, the opening was barricaded for the night; the sailors being forbidden to enter it, lest they should injure the decorations …

All the next day, we spent at work in and about the Speos [the chamber] … The Idle Man [another unnamed traveling companion] and the Painter took measurements and surveyed the ground round about, especially endeavouring to make out the plan of certain fragments of wall, the foundations of which were yet traceable.

They found that the Speos had been approached by a large outer hall built of sun-dried brick, with one principle entrance facing the Nile, and two side-entrances facing northwards.

The southern boundary wall of this hall, when the surface sand was removed, appeared to be no less than 20 feet in thickness … Deeming it impossible that this mass could be solid throughout, the Idle Man set to work with a couple of sailors to probe the centre part of it, and it soon became evident that there was a hollow space about three feet in width running due east and west down not quite exactly the middle of the structure.

All at once the Idle Man thrust his fingers into a skull! … The next instant his hand came in contact with the edge of a clay bowl, which he carefully withdrew. It measured about four inches in diameter, was hand-moulded, and full of caked sand. He now proclaimed his discoveries, and all ran to help in the work. Soon a second and smaller skull was turned up, then another bowl, and then, just under the place from which the bowls were taken, the bones of two skeletons all detached, perfectly desiccated, and apparently complete. The remains were those of a child and a small grown person—probably a woman. The teeth were sound; the bones wonderfully delicate and brittle. As for the little skull (which had fallen apart at the sutures), it was pure and fragile in texture as the cup of a water-lily.

After-reflection convinced us that we had stumbled upon a chance Nubian grave, and that the bowls (which at first we absurdly dignified with the name of cinerary urns) were but the usual water-bowls placed at the heads of the dead. But we were in no mood for reflection at the time. We [were] sure that the Speos was a mortuary chapel; that the vault was a vertical pit leading to a sepulchral chamber; and that at the bottom of it we should find … who could tell what? Mummies, perhaps, and sarcophagi, and funerary statuettes, and jewels, and papyri, and wonders without end! That these uncared-for bones should be laid in the mouth of such a pit, scarcely occurred to us as an incongruity. Supposing them to be Nubian remains, what then? If a modern Nubian at the top, why not an ancient Egyptian at the bottom?

The Painter, meanwhile, had also been at work. Having traced the circuit and drawn out a ground-plan, he came to the conclusion that the whole mass adjoining the southern wall of the Speos was in fact composed of the ruins of a pylon, the walls of which were seven feet in thickness, built in regular string-courses of moulded brick, and finished at the angles with the usual torus, or round moulding. The superstructure, with its chambers, passages, and top cornice, was gone; and this part with which we were now concerned was merely the basement, and included the bottom of the staircase.

The Painter’s ground-plan demolished all our hopes at one fell swoop. The vault was a vault no longer. The staircase led to no sepulchral chamber. The brick floor hid no secret entrance. Our mummies melted into thin air, and we were left with no excuse for carrying on the excavations. We were mortally disappointed … We had set our hearts on the tomb; and I am afraid we cared less than we ought for the pylon … I do not believe we once asked ourselves how it came to pass that the place had remained hidden all these ages long; yet its very freshness proved how early it must have been abandoned. If it had been open in the time of the successors of Rameses II, they would probably, as elsewhere, have interpolated inscriptions and cartouches, or have substituted their own cartouches for those of the founder. If it had been open in the time of the Ptolemies and Caesars, travelling Greeks and learned Romans, and strangers from Byzantium and the cities of Asia Minor, would have cut their names on the door-jambs and scribbled ex-votos on the walls. If it had been open in the days of Nubian Christianity, the sculptures would have been coated with mud, and washed with lime, and daubed with pious caricatures of St. George and the Holy Family. But we found it intact—as perfectly preserved as a tomb that had lain hidden under the rocky bed of the desert. For these reasons I am inclined to think that it became inaccessible shortly after it was completed …

It happens sometimes that hidden things, which in themselves are easy to find, escape detection because no one thinks of looking for them …

The Painter wrote his name and ours, with the date (February 16th, 1874), on a space of blank wall over the inside of the doorway; and this was the only occasion upon which any of us left our names upon an Egyptian monument.

I am told that our names are partially effaced, and that the wall-paintings which we had the happiness of admiring in all their beauty and freshness, are already much injured. Such is the fate of every Egyptian monument, great or small. The tourist carves it all over with names and dates, and in some instances with caricatures. The student of Egyptology, by taking wet paper “squeezes,” sponges away every vestige of the original colour. The “collector” buys and carries off everything of value that he can get; and the Arab steals for him. The work of destruction, meanwhile, goes on apace. There is no one to prevent it; there is no one to discourage it. Every day, more inscriptions are mutilated—more tombs are rifled—more paintings and sculptures are defaced. The Louvre contains a full-length portrait of Seti I, cut out bodily from the walls of his sepulchre in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings. The Museums of Berlin, of Turin, of Florence, are rich in spoils which tell their own lamentable tale. When science leads the way, is it wonderful that ignorance should follow?