Five years before her work as a nurse in the Crimean War (1854–1856) brought her international fame as the saintly “Lady with the Lamp,” Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) was a young Englishwoman ready to buck convention. At 29, she was attractive, well-traveled and well-read, and had already turned down several offers of marriage. Ardently believing that God had called her to a life of service, she found herself drawn to nursing—work that in the mid-19th century was popularly associated with drunkenness and promiscuity. Her wealthy parents were appalled, and the resulting tension within the Nightingale household affected Florence’s health. When longtime family friends Charles and Selina Bracebridge invited her to accompany them on a cruise up the Nile, she jumped at the chance to leave her Hampshire home. The trio set out for Egypt in the fall of 1849 and spent over three months sailing from Cairo to Ipsamboul (Abu Simbel) and back. They eschewed travel by steamer—a speedy, newfangled mode of transportation—and chose instead to sail on a traditional dahabiah, a kind of flat-bottomed houseboat. Florence filled her letters home with vivid observations of the desert landscapes and archaeological sites she saw along the Nile. Her correspondence [the following excerpts are taken from Letters from Egypt: A Journey on the Nile 1849–1850, Anthony Satin, ed. (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987)] is enlivened by literary and historical references (she had boned up on things Egyptian with an Arabic scholar prior to setting off on her trip) and a sometimes droll sense of humor. Yet what we feel most powerfully is Florence Nightingale’s intense and direct awareness of God’s presence—even in the ancient ruins of Thebes. She wonders how “people come back from Egypt and live lives as they did before.” Certainly she didn’t.

Karnak, the last night of 1849

My Dear People,

Yes, I think your imagination has hardly followed me through the place where I have been spending the last night of the old year. Did you listen to it passing away and think of me? Where do you think I heard it sigh out its soul? In the dim unearthly colonnades of Karnak, which stood and watched it, motionless, silent, and awful, as they had done for thousands of years, to whom, no doubt, thousands of years seem but as a day [see Psalm 90:4]. Would that I could call up Karnak before your eyes for one moment, but it “is beyond expression.”

No one could trust themselves with their imagination alone there. Gigantic shadows spring up on every side; “the dead are stirred up for thee to meet thee at thy coming, even the chief ones of the earth,” and they look out from among the columns, and you feel as terror-stricken to be there, miserable intruder, among these mighty dead, as if you had awakened the angel of the Last Day. Imagine six columns on either side, of which the last is almost out of sight, though they stand very near each other, while you look up to the stars from between them, as you would from a deep narrow gorge in the Alps, and then, passing through 160 of these, ranged in eight aisles on either side, the end choked up with heaps of rubbish, this rubbish consisting of stones twenty and thirty feet long, so that it looks like a mountain fallen to ruin, not a temple. How art thou fallen from heaven, oh Lucifer, son of the morning!

Thebes, New Year’s Day, 1850

My Dear People,

I open my eyes, to wish you a happy New Year, and my eyes look upon the obelisk and colonnade of Luxor, under which we lie at anchor, with the sun rising behind them … Nothing can equal the first impression of seeing Thebes. We landed [yesterday], and ran up to Luxor, to see her temple before dark, her one obelisk still standing fresh, and unbroken as the day it was cut, before the propylaeum, at the gate of which sit two colossi of Ramesses II [1290–1224 B.C.]; but alas! the faces gone, the figures covered up to the elbows. A third colossus, a little farther, sat at the corner of the propylaeum; the crown now only marks the spot, projecting above the sand. There stands the colonnade of the seven lotus columns, immeasurably vast, against the sky. The Holy Places are all blocked up, choked with huts and sand, but the cartouches, where you can see them, are all so fresh and sharp, that even our inexperienced eyes could read the legends of the Kings.

Off Hermonthis, January 2, 1850

The colourlessness of Egypt strikes one more than anything. In Italy there are crimson lights and purple shadows; here there is nothing in earth, air, sky, or water, which one can compare in any way with Europe; but with regard to absence of colour, it is striking. It was probably on account of this that the ancient Egyptians painted so much: and one does not feel the colouring of the sculptures barbaric, but necessary; for everything, ground, rivers, houses, men, camels, asses, palm trees, are the same dusty-brown “sad-colour” … Thebes takes so much out of one. I fell asleep on my ass, riding home a mile and a half from Karnak. It was no use trying to think or to feel anything. … The “two witnesses,” the Pair at Thebes [the colossi of Memnon], sit with their faces to the river. There is something uncanny about these two portraits of Amunoph III [Amenophis III (1390–1352 B.C.)], as about the two of Ramesses II at the propylaeum gate of Luxor Temple. It is a truly Egyptian idea, and makes one creep as if one saw one’s own self sitting opposite to one. They must have looked still more curious when perfect and fresh; but even in their present disfigured state, one cannot get accustomed to the repetition.

I could not (between ourselves) get up a single feeling of enthusiasm about the Pair, nor indeed, about the Pyramids, from first to last: bigness does not make greatness. The difference between Thebes and the Pyramids seems to me the same as between Milton’s and Dante’s imaginations. When Dante wants to impress you, he gives an all-material measurement of the size of his spirit. His head is 72 by 35 by 19; and what idea of sublimity does that give you? So it is with the Pyramids; there is nothing but size about them to make their ugliness great. Milton and Thebes knew better.

At Ipsamboul, January 17, 1850

My Dearest People,

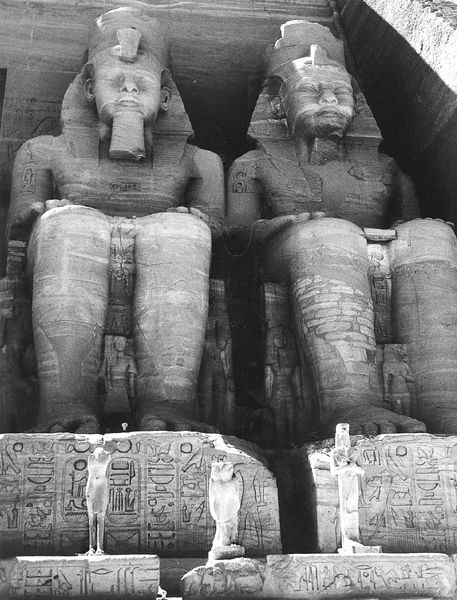

Here we are arrived at the last and greatest point of our voyage—greatest it is in all respects—I can fancy nothing greater. All that I have imagined has fallen short of Ipsamboul (of the great temple of the Osirides), and thank God that we have come here … There they sit, the four mighty colossi, seventy feet high, facing the East, with the image of the sun between them, the sand-hill sloping up to the chin of the northern-most colossus … It makes the impression upon one that thousands of voices do, uniting in one unanimous simultaneous feeling of enthusiasm or emotion, which is said to overcome the strongest man. Yet the figures are anything but beautiful; no anatomy, no proportion; it is a new language to learn, and we have no language to express it.

The Valley of the Kings, February 10, 1850

Dearest People,

The Queen’s wedding day, I think—what a long way I do seem from Victoria’s wedding day! Nofriari’s I feel much more at home with … The Valley of the Kings seems, though within a mile of Thebes, as if one arrived at the mountains of Kaf, beyond which are only “creatures unknown to any but God”—so deep are the ravines, so high and blue the sky, so absolutely solitary and unearthly, so utterly uninhabitable the place. One look at the valley would give you more idea of the supernatural, the gate of Hades, than all the descriptions, sacred or profane. What a moment it is the entering that valley, where in those rocky caverns, the vastness and the gloomy darkness of which are equally awful, the kings of the earth lie, each in his huge sarcophagus, with the bodies of his chiefs, each in their chamber, about him; and where, about this time, they are to return, to find their bodies (where are they now?) and resume their abode on earth—if purified by their 3000 years of probation, in a higher and better state, if degraded, in a lower. I thought I met them at every turn in those long, subterraneous galleries, saw their shades rising from their shattered sarcophagi.