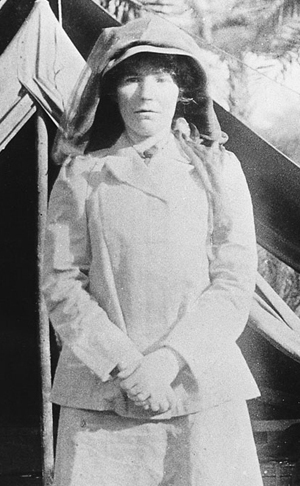

In 1921, the British Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill, convened an international summit to discuss the fate of England’s Arab territories. The guest list for the Cairo Conference included Arab potentates, European diplomats, future heads-of-state and one extraordinary woman: the indomitable Gertrude Bell. The daughter of a wealthy English industrialist, Gertrude Bell (1868–1926) spent most of her adult life flouting convention. At the age of 17, she shocked London society by enrolling at Oxford University—where she studied modern history and became the first woman to graduate with honors. After college, she took up Alpine climbing and joined the suffragette movement. But Bell’s greatest and most enduring passion was the archaeology of the Middle East. Between 1900 and 1914, she embarked on a series of archaeological expeditions to destinations as diverse as ancient Babylon and the remote Saudi Arabian citadel of Hayil. Accompanied by a handful of native guides and her Armenian factotum, Fattuh, she rode deep into the Arabian desert, braving scorching heat, blinding sandstorms and warring Bedouin tribes in her search for antiquities. During World War I, Bell became the British army’s first (and only) female political officer, supplying vital intelligence information to field operatives like T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia). At the Cairo Conference, Bell helped negotiate the independence of Iraq. She spent her final years establishing the Baghdad Museum and serving as one of King Faisal I’s most trusted advisors. Although Bell wrote several best-selling accounts of her travels, her adventurous spirit is best expressed in the hundreds of intimate, chatty letters she sent to her parents. These letters reveal her restless, probing intellect, insatiable hunger for excitement and occasional bouts of loneliness and depression. The following excerpts describe one of Bell’s first excursions into the Iraqi desert and her thrilling discovery of an eighth-century A.D. Persian palace, now known as Ukhaydir.—Ed.

Saturday, March 21 [1909]

We are safely through our first day, praise be to God! We traveled 10 hours across open naked desert and never saw a soul all day … At last about half past 4 we came to a place called the Father of Asphalt and there the pitch comes out of the ground from 8 springs and flows over the empty desert. Here we expected to find Arab tents and indeed from far away I had seen a man through my glasses, but when we got near we could find nothing. So we resolved to cross the pitch beds and were presently engaged in a wilderness of pitch, some hard and some soft, from which it seemed probable that we should never escape. Moreover it was getting late and it was essential that we should find the Arabs. You understand, if you camp near them you are their guest and they will not touch you or yours, but if you are camped alone they will raid you at pleasure. At last Fattuh [Bell’s Armenian servant and guide] and I caught sight of some black tent roof outside the pitch beds; we extricated ourselves with difficulty, rode up to the tents, gave the salaam and asked where was the Sheikh and what was his name. His tent was a few minutes further on; we rode slowly up to it so they might not think we were raiders, gave the salaam and were received with open arms …

Friday, March 26 [1909] Khethar [Ukhaydir]

[Yesterday] we came to the most wonderful building I had ever seen. It is an enormous castle, fortress, palace—what you will—155 metres x 170 metres [508 feet by 558 feet], the immense outer walls set all along with round towers and about a third of the inside filled with court after court of beautiful rooms vaulted and domed, covered with exquisite plaster decoration, underground chambers, some built with columns, some set round with niches, in short the most undreamt of example of the finest Sassanian [Persian] art that ever was. It is not even in the map, it has never been published, I never heard its name before; I hear from the Arabs that a foreigner came here last year and worked at it for a few days, but who he was I don’t know. As soon as I saw it I decided that this was the opportunity of a life time. It doesn’t matter the least if someone else publishes it before I do, I myself shall learn more of Eastern art of the 6th century by working at it than I should learn from all the books that ever were. I place it at the time of Ctesiphon [an early capital of the Persian empire, it was destroyed in the seventh-century A.D.], but I expect that it was built not for the Sassanians but for the Lakhmid princes [a pre-Islamic dynasty in what is now Iraq]. The Arab historians relate that when the Mohammadans first conquered this country in the 7th century they stood in amazement before the Lakhmid palaces; as far as I know this is the only one that remains and it is almost perfect … I set out with a measuring tape and a foot rule to plan the whole place. I worked yesterday for 5 hours and today for 8 and I’ve got nearly the whole thing sketched in; tomorrow I shall begin to draw it out …

Khethar [the palace] is occupied by some Arabs from … Ibn Rashid’s country [central Arabia]. They are without doubt the nicest people ever known. The Sheikh Ali, a splendid creature with black hair falling in plaits on either side of his face, put the whole castle at my disposal. He sits all day in the great hall inside the main gate and two or three times a day he sends me bitter black coffee to help me through my work. It is more reviving than words can say. Sometimes he comes trailing out in his long white robes (it is so hot that in the middle of the day he throws off his black cloak) and sits with me for a few minutes while I drink the coffee and listen to tales of Nejd [a great desert of central Arabia] related in a rolling speech worthy of the great Arab days. His people live in the halls and courts of the Lakhmid princes; the men take it in turns to hold my measuring tape, carry my camera and so on. In a day they have learnt exactly what it is I want and they are infinitely useful to me for I simply have to walk after them with my sketch book and write down the figures from the tape.

The accuracy of the building is astounding. Over distances of from 30 to 40 metres you don’t find discrepancies of so much as 10 centimetres in the chambers and passages that balance one another.

Monday, March 29 [1909]

… It has been an immense pleasure to be busy with a building as splendid and as exact as Khethar [Ukhaydir] and to watch all the ingenious schemes of the architects. Some of the most curious are the roofing systems, all contrived, I imagine, in order to keep out the heat. First of all the walls and vaults are very thick; between the parallel barrel vaults, and parallel with them, they ran long vaulted air passages like tubes opening to the outer air with tiny slits of windows; above all, between the top of the main vaults and the sun, there is, as you might say, an air roof [of] tiny tunnels covered over with the true flat roof of stone and plaster. The result is that the rooms are always cool and fresh, and you go from court to court down the long passages and never realize the blazing heat outside. Once or twice I have come across secret chambers with no visible door—treasure chambers I suppose. You can see them now because the Arabs have broken holes into them. And often you find, opening out of the living rooms, a long narrow vaulted corridor, unlighted, where you could go and sit when the heats were greatest. The only thing I haven’t planned is the underground vaults. Some one else may do that, I can’t go scrabbing about in the dark over piles of fallen stones. The Arabs pass barefoot and silent up and down the stairs and passages, gather round hearths scooped out of the floor of the queen’s chambers, live and starve and die among the ruins of a great luxurious civilization—their own, but long forgotten by them.

One night Sheikh Ali asked me if I should like to hear a man sing to the rebaba—the rebaba is a sort of fiddle with a single string. We went into the Great Hall just inside the main door, where the Sheikh makes coffee all day long, and there sat down on mats and cushions round the hearth. The fire of thorns sent up a little flickering light … The man next me took the rebaba and began playing a long prelude; then he said “I will sing you the song of ‘Abd ul Aziz ibn Rashid” [a former emir of central Arabia]. So he sang in praise of the last dead prince of the Beni Rashid, a great patron of the arts he was, a leader of raids, rich and powerful, and lately overthrown and killed in battle. At times, the Sheikh’s brother, Ma’ash, got up and moved round the circle with the coffee cups, or someone bent forward over the embers and lighted his pipe where the fire was brightest. The thin melancholy music rose up into the huge blackness of the vault above, and across the wide opening at the end of the hall, where the wall had fallen away, was spread the deep still night, a sky half full of moon light and half filled with the soft gleam of faint stars. “Balina wa ma tabla en nujum et tawali’u”—I could think of nothing but Lebid’s splendid verse: “We wither away but they wane not, the stars that above us rise; the mountains remain after us and the strong towers.”

Last night my castle gave me a different entertainment. It was a wonderful still night, the immense desert stretching away into infinity under the moon … Suddenly a rifle shot rang out and a bullet whizzed over us—near enough for us to hear the sound of it. All my men jumped up and I could hear Fattuh putting the muleteers as outposts round the camp. I got up too and put on clothes in a hurry and came out to see the fun … Presently Ali and some others hurried past us, all armed in some fashion, and Fattuh, all eagerness, ran off with them into the desert. I climbed up onto a heap of ruins to watch them but they soon disappeared into the glimmering moonlight. But a few minutes later we saw shots flash out red in the distance and wondered whether they came from our people or from the others. After about a quarter of an hour Ali and his men returned, singing a wild song as they came, their rifles over their shoulders, their white robes gleaming in the moon … They declared that the enemy had been raiders of the Thafi’a, a hostile tribe. Ali had seen at sunset from the castle walls men lurking in the distance and had posted a watch when night fell … It has blown a dust storm the whole long day; now to camp or to work in a dust storm are the worst evils known to man. My tents are uninhabitable and I have taken refuge in a remote room of the palace.

Letters courtesy of the Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne; the Gertrude Bell Papers are available from the library’s Web site: www.gerty.ncl.uk