The new Indiana Jones movie, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, seems to be inspiring kids to become more interested in archaeology. As I was about to pick up your latest BAR, I found a group of kids reading it and talking about Indiana Jones and how archaeology is conducted. Indiana Jones is introducing archaeology to a younger generation.

Paul Dale Roberts

Elk Grove, California

Please see our coverage in

Strata and “In Praise of Indiana Jones”.—Ed.

Editor Not Perfect

I am a very conservative Christian. I hold firmly to the inspiration, inerrancy and infallibility of Scripture (“Should I Cancel My Subscription?” Q&C, BAR 34:03). But BAR is one of my most important “friends.” There are often articles with which I disagree. Over the years I have learned just how accurate the Bible really is and how both science and archaeology support the Word (including the six-day Creation). I see the mistakes and faulty presumptions that even people with lots of letters after their names make.

I find Hershel Shanks to be a man of honor and integrity (Can I get a year’s subscription for this, Hershel?) who is willing to fight for the truth, as he sees it. He is attacked and vilified by many in the field of archaeology, yet I have seen nothing in all my readings that substantiates any charges. In fact, he invariably prints many such attacks so his readers know the “whole story.”

This is not to say that he is perfect. In a recent issue he had four scholars talking about whether or not archaeology undercut their faith (“Losing Faith,” BAR 33:02). None of the four was what I would call a conservative Christian. Maybe he will correct this mistake in the future.

I say to you, any conservative Christians, do not cancel your subscription to BAR. Give it as a gift to others like you. They may not always see things in BAR with which they agree, but they will always profit from BAR.

Pastor Joseph E. Mason Jr.

Yacolt, Washington

Documentary Hypothesis Confirmed

In his critique of the Documentary Hypothesis (“Don’t Butcher the Text,” Q&C, BAR 34:03), Rabbi Yosef Reinman states: “The very idea [of the Documentary Hypothesis] is amazing. Never in the history of the world has a book been spliced together from multiple documents by the kind of elaborate surgery that the critics perform on the Bible text.”

I wonder how hard Rabbi Reinman looked before concluding that no book was ever composed this way. In fact, there are several examples, from ancient to modern times, of exactly this process. As Biblical scholars have known since the late 19th century, the second-century Syrian bishop Tatian composed the Diatessaron, a single running biography of Jesus, by splicing together the four Gospels using exactly the same techniques supposed by the Documentary Hypothesis.

In the same way, in the version of the Torah used by the Samaritans, the two separate versions of Moses’ appointment of subordinate judges found in Exodus 18 and Deuteronomy 1 were spliced together in a single narrative. So were the two Mt. Sinai narratives from Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5.

The Temple Scroll from Qumran was composed by splicing together passages from Deuteronomy and other books of the Bible plus several extrabiblical works. In modern times, the Hebrew writers Hayim Nachman Bialik and Yehoshua Hana Rawnitzki composed their classic anthology of Jewish legends (Sefer Ha-Aggadah) by using very similar techniques.

In the 1980s I edited a volume, Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism, in which several colleagues and I presented these and other examples of such methods. The book was reprinted in 2005 by Wipf and Stock Publishers of Eugene, Oregon. There, readers will see that the methods of composition supposed by the Documentary Hypothesis are very far from being outlandish and unparalleled in the history of the world.

Jeffrey H. Tigay

Ellis Professor of Hebrew and Semitic Languages and Literatures

Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

The author wrote the The JPS Torah Commentary on Deuteronomy (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1996).—Ed.

In a recent item in Strata (“Ritual Bath or Swimming Pool?” BAR 34:03), Hershel Shanks reports on a scholarly debate concerning the huge Pool of Siloam (nearly 200 feet long and 160 feet wide) recently discovered in Jerusalem by archaeologists Ronny Reich and Eli Shukron, who identify it as a ritual bathing pool, or mikveh (the largest in the entire city), meant especially for public use by crowds coming to the Holy City for the three pilgrim festivals (Passover, Tabernacles and Weeks).

Israeli scholar Yoel Elitzur, however, argues that what Reich and Shukron have found is probably a Roman-style swimming pool. It cannot be a mikveh, according to Elitzur, because bathing in a mikveh must be in the nude. This would indeed seem to present a problem, given the Jewish abhorrence of public nudity.

I believe, however, that the presumption that ritual bathing always had to be done in the nude is a false one. While those purifying themselves in smaller, private mikva’ot undoubtedly did so without clothing, there are several indications that there was no requirement that ritual purification be done unclothed in order for the purification to be valid.

The Bible itself says nothing about this issue. However, we do have indirect information from other sources. While discussing the celibate community of Essenes, Josephus states that, when the men purify themselves, they wear a loincloth (War II.8.5 §129) given to them when they entered the community (War II.8.5 §138). When discussing those Essenes who married, he states that, when men purify themselves, they wear a loincloth and, when women purify themselves, they wear a dress (War II.8.13 §161). It is generally recognized that the rules of the community at Qumran regarding ritual purity were more strict than those of other sectors of Judaism. If this is so, then the fact that the Essenes could wear a loincloth or dress would indicate that this would also be possible for other Jews whose interpretation of the Law was less strict than that of the Essenes.

The most detailed discussion of ritual bathing that we have is the earliest rabbinic code (c. 200 C.E.), the Mishnah, where an entire tractate is devoted to mikva’ot. One of the issues addressed by this tractate is what “interposes” between an unclean object and the water of purification.1 The main concern regarding ritual immersion is that the water be able to contact all parts of the person or object. For example, pitch that was stuck to a vessel would “interpose” and therefore the vessel would not be considered clean even after immersion since the pitch prevented the water from reaching one part of the surface of the vessel. The same principle is applied to objects that would interpose between the human body and water. For example, if a person clamped any parts of the body together (e.g., one’s fingers or lips) so that water could not reach between the parts, the person would not be rendered clean.

The Mishnah also addresses the issue of clothing. It was the common opinion of the rabbis that strips of wool or linen would “interpose” between the skin and the water and so the person would remain unclean. These would be strips that were bound closely to the skin. However, Rabbi Judah argued that even strips of wool did not interpose since the water could penetrate them.

Whatever opinion ended up being considered the correct one, the only reason for such a ruling in the first place was that it was common for people to wear some items of clothing while immersing. If this was true of strips wrapped closely to the body, then all the more so would a loose-fitting garment be allowed.

In first-century Palestine, clothing typically consisted of two loose-fitting garments: an undergarment or tunic, called a chiton in Greek, and an outer garment or mantle, called a himation. Both of these garments were loose-fitting and would allow proper circulation of water during immersion. Of course, only one garment would need to be worn in the mikveh. The other one would be dry and donned on emergence.

Hence, there should be no hesitancy in identifying the Pool of Siloam as a mikveh.

Urban C. von Wahlde

Professor of New Testament

Loyola University Chicago

Chicago, Illinois

Perhaps I should not be surprised that a scholar who has advocated a Biblical nihilism and has recommended that Biblical studies should be “tasked with eliminating completely the influence of the Bible in the modern world” would launch an attack on the discipline of Biblical archaeology and on a magazine that is Biblical archaeology’s most important outlet. In the May/June “First Person” column by Professor Hector Avalos, as well as his book from which this column is taken, Professor Avalos criticizes not only the policies of BAR and its editor, he also questions the legitimate existence of the entire complex of Jewish and Christian religion in the United States, its Biblical base and its relationship to the academic discipline of Biblical studies, to wit, the Society of Biblical Literature—a formidable task indeed! What would be required for such an endeavor, however, is knowledge of the realities of American religious life and Biblical scholarship in general, as well as of the details of controversial issues in present debates. Unfortunately, Professor Avalos reveals a deep ignorance in both respects.

The reality is that both Judaism and Christianity depend upon the Bible. The Bible is their book of law and morality, their source of inspiration and worship, of consolation in sorrow and of festive celebration. The suggestion that the modern world does not need this book at the same time recommends the complete elimination of these Bible-based religions. This is not only preposterous, but it reveals a complete lack of understanding of what Professor Avalos calls “the modern world.” His “modern world” is a fiction in his mind that has no relationship to reality.

As for BAR, Professor Avalos off-handedly characterizes it as a journal that “has served Biblical education well in some cases and badly in others” creates the impression that about half of its content belongs to the latter category. He then proceeds to draw a caricature of some of its articles as if this were the kind of thing to which BAR was mostly committed. This is far from the truth.

Most of its articles are well-reasoned and well-documented presentations of good scholarship. To be sure, some are controversial—scholars disagree on interpretations of archaeological as well as literary materials—but that is the normal business of scholarship. Does Professor Avalos, claiming to be a scholar, not know that?

In fact the more controversial articles and opinions have served a very important purpose. The albeit-illegal publication of unpublished material from the Dead Sea Scrolls broke a deadlock that many had unsuccessfully tried to do for many years.

It was during the year of my presidency of the Society of Biblical Literature that the society accepted a free-access policy, which had successfully been applied in the process of the publication of the Nag Hammadi Codices (first: publication of a facsimile; second: publication of a preliminary translation; third: critical editions of all documents). But we were never been able to convince scholars involved in the publication of the scrolls to follow the same procedure. Thanks to BAR’s bold move to publish some unpublished texts, the deadlock was finally broken. Professor Avalos recognizes this; but is this part of BAR’s scandalous behavior?

Then there is the accusation that BAR is biased because it calls Professor Frank Cross a friend of Israel and the late Professor John Strugnell an anti-Semite, both Harvard colleagues of mine. This is not bias; it is a statement of a fact. I have known for decades that John Strugnell believed in Christian supersessionism.

Moreover, BAR’s seemingly offensive comments about Elisha Qimron are justified in many ways.a That Hershel Shanks has been found guilty by an Israeli court of violating Qimron’s copyright in the translation does not make him a criminal but rather a saint—if there is something like that in Judaism! Qimron has never revealed that the translation of the controversial Dead Sea Scroll known as MMT was primarily the work of John Strugnell, who never got due recognition for his work.

Professor Avalos also cites as BAR’s “competitive nature” Hershel Shanks’s criticism of the National Geographic’s publication of the Gospel of Judas.b On the contrary, he should have congratulated BAR for this critique! The publication of this document by the National Geographic was a scandal. The scholar entrusted with the translation, Marvin Meyer, violated the free-access statement of the scholarly society [the Society of Biblical Literature], of which he is a member. To his detriment, numerous major mistakes in his translation have now been discovered.c 2 This could have been avoided if Marvin Meyer or whoever would be entrusted with its publication had allowed fellow scholars in the field of Coptic studies to discuss this Coptic text before the appearance of the first English translation. What Hershel Shanks wrote, calling attention to the scandal of National Geographic’s publication of this text, was exactly right and has been confirmed by subsequent scholarly investigations.

I shall refrain from setting the record straight on other examples of Professor Avalos’s caricature of BAR. More important is a consideration of the fundamental and important role that BAR has been playing in the concert of Bible and archaeology. There was once another popular journal, Biblical Archaeologist, founded by my former Harvard colleague and prominent archaeologist G. Ernest Wright. In its first years, BAR competed with this journal. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR), under whose auspices it was published, however, decided to change the name of this publication to Near Eastern Archaeologist, since it seemed to the leaders of this society that the name “Biblical” was odious (Professor Avalos evidently agrees with that judgment!). This was done by ASOR after the vast majority of the subscribers rejected such a change of the title. The result was that subscribers interested in the Bible (including me) discontinued their subscription. This makes BAR and Hershel Shanks’s Biblical Archaeology Society the only player in the field. Courageously this magazine alone holds up the torch of a scholarly outlet in this important area, although the very name “Biblical” combined with the world of a scholarly discipline—including archaeology—seems to be deplorable for Professor Avalos as well as the leaders of ASOR, who have largely abandoned their responsibility of a publication with an appeal to the general public in this field of study.

It is exactly here that Professor Avalos’s lack of understanding of the realities of Biblical scholarship is most evident. He apparently is unable to see this reality: The relationship of American religious life, Bible and scholarship is a vital and undeniable factor in our society—especially in the United States—however controversial.

Helmut Koester

Former SBL President

Professor Emeritus

Harvard Divinity School

Cambridge, Massachusetts

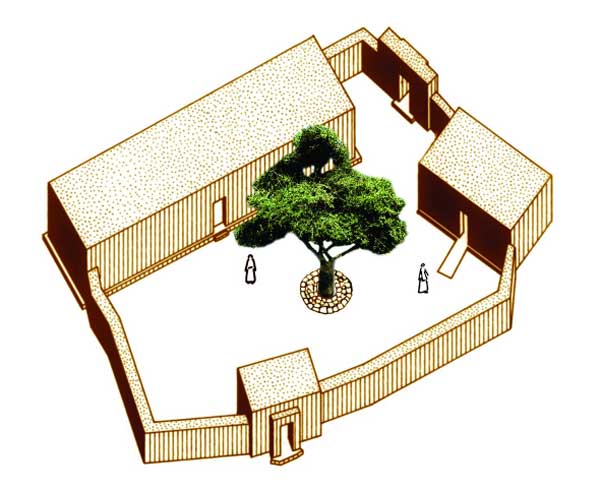

Sacred Tree or Water Installation?

In the caption to the picture of the circular stone installation in the courtyard of the Chalcolithic temple at Ein Gedi (“Ein Gedi’s Archaeological Riches,” BAR 34:03), you state that “One scholar has suggested it was not for water [as the excavation report claims] but to protect a sacred tree.” The anonymous scholar who made that suggestion is me. The proposal was made in “A Sacred Tree in the Chalcolithic Shrine at En Gedi: A Suggestion,” Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 18 (2000), pp. 31–36.

Amihai Mazar

The Institute of Archaeology

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Jerusalem, Israel

Professor Mazar’s article makes a powerful suggestion. Professor David Ussishkin’s excavation report posits the installation’s use for water lustrations, but no drainage channel has ever been found, as pointed out in the BAR article. Nor has any evidence of plaster been found on the inner surface of the round installation, so how could the installation have held a liquid? Moreover, as Mazar points out, the inner part of the installation was lined with seven large, flat stones standing on their narrow sides. They lean toward the center as if constructed around something that is now missing.

Sacred trees were common in the ancient Near East, as they have been in more modern times. In the Bible, sacred trees are frequently condemned as one of the foreign, non-Israelite symbols of worship (see Deuteronomy 12:2, 28:36; 1 Kings 14:23; 2 Kings 17:10; Jeremiah 17:2; Ezekiel 6:13 and 20:28). These sacred trees are often associated with the goddess Asherah. A more modern example is the old oak tree located north of Hebron that is identified in Muslim tradition with Abraham’s oaks at Mamre (see Genesis 18).—Ed.

Scratch ’n’ Sniff

In “Ein Gedi’s Archaeological Riches,” I believe the two inscribed pottery sherds described as “tags” are actually scrapers and fleshers used to work animal hides. The shape is the same as our local “pinch stones,” featuring three positions for the thumb and fingers to hold the sherd to scrape the hides. Labeling the object helps prevent discarding.

Perhaps the perfumes were used for the hides, not the people.

William A. McCarthy

Springfield Center, New York

Synagogue Swastika

The swastika found at Ein Gedi should be investigated further. In American Indian culture, the symbol has special meaning. The crossed members of the symbol point to the four cardinal points of the compass, north, east, south and west. The portions you refer to as arms do not point counter-clockwise; they represent forces moving in a clockwise direction, rotating the crossed members through the four seasons in the direction of the Earth’s rotation.

Conversely, the Nazi swastika is being rotated counter-clockwise as though opposing the symbolism of the Ein Gedi mosaic. Is it possible that it was intended to serve as an anti-Semitic, anti-Christian symbol?

James D. Crownover

Elm Springs, Arkansas

Yitzhak Magen argues that Nebi Samwil is Biblical Mizpah of Benjamin (“Nebi Samwil: Where Samuel Crowned Israel’s First King,” BAR 34:03), and against its identification with Tell en-Nasbeh (south of modern Ramallah, about 8 miles north of Jerusalem).

Attempts to locate a Biblical toponym must deal not only with the textual and archaeological data that supports one’s own position, but they must also refute the material in support of rival candidates. In his article Magen deals with the scanty archaeological materials from Nebi Samwil and the Biblical texts that support his identification, but he largely ignores the data, especially the archaeological data, in support of the Tell en-Nasbeh location.

Both sites have only circumstantial evidence in their favor; no decisive inscription has yet been found to decide the argument. However, when deciding between rival candidates for a Biblical toponym, all the evidence must be used. In the end only the passage from 1 Maccabees 3:46, which locates Mizpah “opposite Jerusalem” can really be said to favor Nebi Samwil. Other evidence is either neutral or favors Tell en-Nasbeh, especially 1 Kings 15 (see my analysis of this passage in the Web article referred to after this letter).

Archaeologically Tell en-Nasbeh has produced Iron I materials, a major set of Iron II fortifications and an entire stratum that belongs to the Babylonian-Persian period. These are non-subjective data that accord well with the Biblical texts, including 1 Kings 15, that mention Mizpah.

If Tell en-Nasbeh is not Biblical Mizpah, what is it? Clearly it was an Iron II site of some importance given its massive fortifications. It was also a major site during the Babylonian and Persian periods. Given its proximity to Jerusalem, it would be odd indeed if it were not mentioned by the Biblical authors.

Because of the destruction wrought on the site by later builders, we will never know if Nebi Samwil could have matched Tell en-Nasbeh’s archaeological qualifications as a candidate for Mizpah. This is an unfortunate circumstance. However, based only on the surviving archaeological material, one would have to conclude that Nebi Samwil was founded only in the eighth century B.C., reached a high point in the Persian period and was abandoned in the middle of the Hellenistic period. With that pedigree, it could be virtually any Benjaminite village. There is no doubt that important late material comes from Nebi Samwil, but in this world of subjective analysis, the bulk of the evidence still favors Tell en-Nasbeh as the most likely candidate for Mizpah.

Jeffery R. Zorn

Adjunct Associate Professor

Department of Near Eastern Studies

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York

Ding-Dong

Aren Maeir’s speculation on the exact nature of the ‘opalim is both imaginative and entertaining (“Did Captured Ark Afflict Philistines with E.D.?” BAR 34:03). However, I would contest his minimalistic identification of the seven “phallic-shaped vessels” with holes as “apparently an ancient cultic mobile.” Though on the right track, he fails to recognize an ancient form of our everyday wind-chimes, which we would now call “ding-dongs.”

Chris McBee

Belgrade, Montana

A Philistine Lesson in Song

Many years ago I was caught by our teacher on the way home from school (at which the lesson on the Philistines and the Ark had been taught) singing, “O dem golden hemorrhoids/ O dem golden hemorrhoids/ Golden hemorrhoids I’s goin’ to get/ Sittin’ on dat Golden Throne.”

I think if Aren M. Maeir’s version were available, we would have been expelled.

Eric Mendelsohn

Toronto, Ontario

Mice Spread the Plague

Your article about the captured Ark and the Philistines’ E.D. is a bit bizarre. Did you read the entire verse of 1 Samuel 6:5? Along with the “emerods” there were also mice placed in the Ark. Therefore, as many of us have been taught, the “emerods” would seem to indicate the mice had been spreading the plague and would account for the tumors.

Irene B. Livingston

Phoenix, Arizona

We just returned from BAS’s “Israel at 60” tour. It was the most remarkable travel event of our lives.

BAS promised a unique trip, and [tour leader] Amnon Wallenstein delivered an incredible experience. Thank you for promising a lot and delivering far more.

As detailed as were BAS’s brochure and tour description, they could not adequately describe what BAS and Amnon gave us. Each day was filled with more “ooohs” and “aaahs” and “wows” than any of us could have imagined in advance.

Amnon led us to put our teeth into the Bible and our hands into the earth; it could not have been a more personal immersion into Biblical archaeology and history. The presentations to our group by two of Israel’s top archaeologists, Kurt Raveh and Hillel Geva, and our entry to active digs were more than we expected. When Amnon was able to add to those formal presentations with some informal comments by Gaby Barkay and Dan Bahat (who just happened to be where Amnon was leading his flock), we could not have been more impressed and excited.

Two weeks with Amnon Wallenstein on the BAS tour provided a lifetime of memories and deeper curiosity about Biblical archaeology.

George and Taaron Makrauer

The Villages, Florida

We received a few letters regarding mistaken information about the quarrying process in a caption on page 40 of the May/June issue. Wood swells when it comes in contact with water (as stated correctly on p. 20 of the same issue).

Regarding “In History” (Strata, BAR 34:03): The kingdom of Lydia was the major power in Asia Minor and Media was the Iranian empire that became the Persian empire. (They were not Greek city-states, as we incorrectly stated.)

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Before eating the Sabbath meal on Friday evening, the wine and then the bread are blessed. Saturday evening, the bread is blessed, the last Sabbath meal eaten, and at the Sabbath’s conclusion, the wine is blessed.