Don’t Disrespect the Dead

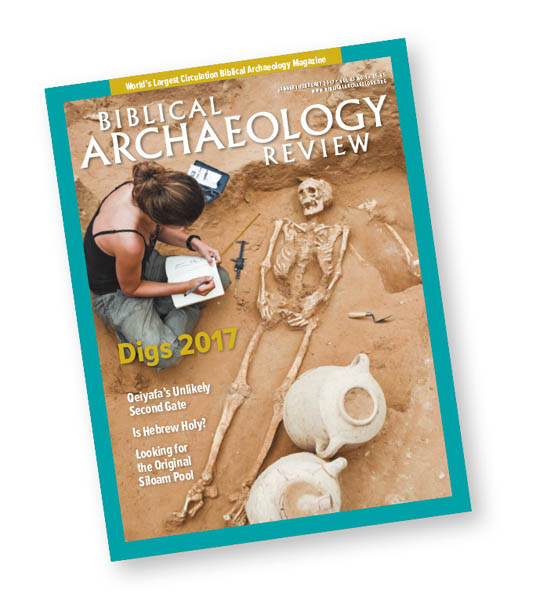

The cover of the January/February 2017 issue confirmed my feelings about your magazine. The skeleton on the cover—head turned, posed with the pottery and tools, looking at the worker taking notes—was contrived and demeaning. Excavating bones or flesh buried for centuries in a far-off land—or digging up my grandfather in Indiana last week—is disrespectful. You should know better.

Indianapolis, Indiana

Bar the Skeletons

I want you to know I enjoy your magazine more than any other I have ever subscribed to. But you might want to consider how many pictures of skeletons you picture. I’m not complaining, but the skeletons of old and unnamed humans are very sad to see.

Vancouver, Washington

True Origins of “Biblical Archaeology”

W.F. Albright did not coin the term “Biblical archaeology,” as stated in the January/February 2017 issue of BAR (“Strata: “Who Did It?”). It existed before he was born! The Society of Biblical Archaeology was created in London in 1870, Samuel Birch having suggested its name. The society published nine volumes of its proceedings from 1878 to 1918 and 40 of its transactions from 1872 to 1893. The Oxford English Dictionary does not list any earlier use.

Emeritus Rankin Professor of Hebrew and Ancient Semitic Languages

The University of Liverpool

Liverpool, England

In the Eye of the Beholder

I thought I might add something to Laurie E. Pearce’s response to Rod Steffes’ letter (see “Queries & Comments,” BAR, January/February 2017) about the persistence of cuneiform writing (Laurie E. Pearce, “How Bad Was the Babylonian Exile?” BAR, September/October 2016).

Regarding the supposed disadvantages of cuneiform writing and writing materials—“cumbersome,” “clumsy,” etc., are often in the eye of the beholder and would not describe how the system works when used by a trained expert. It’s my impression that in the hands of a skilled scribe, writing cuneiform on tablets could be effortless; I think these scribes had it down pat. I also think it’s easy to exaggerate the advantages of an alphabet.

I’ve been working with ancient Egyptian language and texts since I was a kid hanging out in the Brooklyn Museum’s Wilbour Library, and of all the forms of Egyptian, the one that took me longest to master was Coptic—the only one written in an alphabet! Why? Because it lacks the visual and mnemonic clues that the other scripts use—logograms, determinatives, the distinctive sign choices and configurations of a word. I confess that I had to look up a word in Coptic many more times before I remembered it, compared with what we call the “native scripts.”

Also, I taught in China for six years, during which time my two children went to Chinese school, and they have remained fully bilingual and biliterate. They have never found anything cumbersome about reading or writing Chinese. In the historical notes to his “Judge Dee” detective stories, sinologist and diplomat Robert H. van Gulik remarks on how a skilled clerk recording a meeting, court proceedings, etc., in Chinese is doing something very similar to writing in shorthand.

Coeditor, Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities

Adjunct Faculty, Pacifica Graduate Institute

Carpinteria, California

Sistine Chapel Image

While reading BAR as soon as it came (as I always do), I was glad to learn about the reopening of the Santa Maria Antiqua Church in the Roman Forum (Strata: Rome’s OtherSistine Chapel,” BAR, January/February 2017). The accompanying exterior photo, however, depicts the Church of Santa Maria di Loreto, across the Via dei Fori Imperiali from the Roman Forum, and not far from the Piazza Venezia. This 16th-century church faces the Forum of Trajan; in fact, Trajan’s column can be seen in your illustration.

Dennis, Masssachusetts

You are correct.—Ed.

Vita Constantini Citation

David Christian Clausen (Archaeological Views: “Mount Zion’s Upper Room and Tomb of David,” BAR, January/February 2017) says that the anonymous Vita Constantini is roughly dated to the tenth century C.E. Yet in the corresponding footnote you list Eusebius, a fourth-century church historian, as its author. Which is correct—fourth or tenth?

Retired Orthodox Priest

Cortland, Ohio

An editorial error crept into this article in our attempt to give a full citation of the work. David Clausen references the 10th-century Vita Constantini by an anonymous source—NOT the fourth-century work of the same name by Eusebius.—Ed.