Thank you for sharing your thoughts and comments about our Winter 2021 issue. We appreciate your feedback. Here are a few of the letters we received. Find more online at biblicalarchaeology.org/letters.

Timely Content

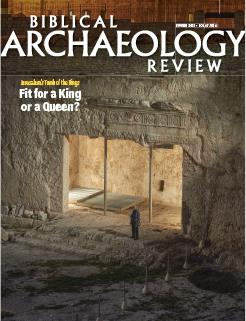

I was reading Herman Melville’s epic poem “Clarel,” which describes a 19th-century journey through the Holy Land, when the Winter 2021 issue of BAR arrived. I was pleasantly surprised to find two places Melville describes featured: the Tomb of the Kings in Jerusalem (Andrew Lawler, “Who Built the Tomb of the Kings?”) and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (“Where Is It?”). Reading the BAR descriptions and seeing the photographs added to my enjoyment of Melville’s challenging poem.

OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA

Shapira Scrolls

In your Winter 2021 issue, the two articles on “The Shapira Scrolls” were fantastic! I enjoyed the way both sides were presented, along with corresponding pictures (exhibits). In a time when people cannot seem to agree on anything, it was refreshing to have a debate presented that allowed for both sides to present their arguments. I found it not only educational but also engaging and fascinating! It allows the readers to think and consider while drawing their own conclusions.

OAK CREEK, WISCONSIN

Thank you for the wonderful debate about the authenticity (or not) of the Shapira Scrolls. Informative, well argued, with no personal attacks. Decades-long familiar BAR authors Ronald Hendel and James Tabor on opposite sides, paired with reputable scholars new to us, Matthieu Richelle and Idan Dershowitz, added to the seriousness of the discussion.

ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA

I really enjoyed the pro/con pieces on the Shapira Scrolls and am challenged to decide which one I find most compelling! The forgery camp seems to base its case on very detailed specifics of paleography, Moses Shapira’s tainted history, and their depiction of the era as one rife with forgeries. The authenticity camp dismisses the paleographic critique by stating that the documents used by the forgery camp to support their claims are patently inaccurate. The literary analysis and the alignment of the scrolls with modern critical theory is fascinating.

My heart wants the authenticity camp to be right, which biases my ability to reach a conclusion, but how exciting would it be if they were authentic?

KENMORE, WASHINGTON

In the argument over the Shapira Scrolls, it seems that “The Case for Forgery” relies only on paleographic analysis. I, for one, am not convinced. It seems the authors think that ancient scribes created their texts with some sort of ancient typewriter, and that all the letters from the scrolls must conform exactly to standard forms. Graphologists will tell you that nobody writes even their signature the same way twice. It may also be the case that a certain scribe liked the way a letter from another script looked and substituted it for the “official” letter. Then there is the matter of the age of the scribe; young and old scribes no doubt wrote their letters differently. And we must not forget that even an experienced scribe could make errors. I grant that paleography is useful for many cases, but when an argument relies solely or mainly on paleographic analysis, no matter how long or well developed the argument, I tend to ignore it. My “vote,” therefore, is for the authenticity of the Shapira Scrolls.

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY

What I find amazing in the antiquities world is how easily experts allow themselves to be fooled by questionable artifacts. I guess the extreme desire to find that one awesome artifact that would change a huge chunk of history is too hard to resist, even when you know the seller (in this case, Moses Shapira) has a long history of selling fraudulent articles. While I actually found the argument for the scrolls’ authenticity compelling, antiquities dealers should be reminded of the fable “The Boy Who Cried Wolf”: Sell enough fakes and even when you have the real thing, you won’t be believed.

STANFIELD, OREGON

In making their case for authenticity, Idan Dershowitz and James Tabor state, in reference to the Book of Deuteronomy, that certain elements have “an odd literary structure, to put it mildly,” and refer to the book’s “disjointed structure.” This structure may be uncommon in written history but is essential to many types of modern fiction, as well as oral literature, such as folktale, myth, and epic, including Homer’s Iliad. Since this architecture suggests that the Bible’s version is based on oral tradition, it weakens Dershowitz and Tabor’s argument for the precedence and extreme antiquity of the “Valediction of Moses,” which has a linear structure more typical of a later literate tradition.

WATERFORD, NEW YORK

Not Lost in Translation

Kudos to Elizabeth Backfish for her excellent article “Not Lost in Translation: Hebrew Wordplay in Greek” (Winter 2021). This was a most interesting and insightful article. It brings to mind many fond memories of an evening class I once took with biblical scholar David Noel Freedman (see Bible Review, December 1993). For three hours, at his house, we would read the Hebrew Bible in the original Hebrew. Freedman pointed out wordplay after wordplay, often evoking much laughter from the group. It seemed to me that if any of us had simply written down all the humor he detected in the Bible, we would have had a bestseller. Backfish’s excellent article continues this tradition of bringing out humor in the Bible.

ST. PETERSBURG, FLORIDA

I appreciated Elizabeth Backfish’s article. However, one sentence is in error: “The Hebrew poet’s choice of ‘esoh for ‘I hate’ is a hapax legomenon, meaning that it occurs only this one time in the entire Hebrew Bible.” First of all, ‘esoh is the infinitive construct of the verb meaning “to do”; second, it is not a hapax legomenon. There is a hapax legomenon in the sentence; it is the next word, setim. The word for “I hate” is the following word, saneti.

PROFESSOR OF HEBREW BIBLE

HOWARD UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF DIVINITY

WASHINGTON, D.C.

ELIZABETH BACKFISH REPLIES:

I am grateful to Dr. Bellis for the correction. The infinitive construct originally identified as the hapax legomenon is actually quite common (occurring about 269 times by my count). The hapax legomenon is the plural noun for transgressors, setim, that follows. The case for wordplay is still strong, since setim is part of the wordplay under consideration, and since many other words in the semantic field of setim are more common (such as khatta’t, ‘aon, and pesha‘ ) and do not contain the “s” sound that makes this example of wordplay so pronounced.

Paul of Arabia

Ben Witherington, in his very interesting article “Paul of Arabia?” (Winter 2021), points out that Paul’s Arabia was the kingdom of the Nabateans, located south and east of the Dead Sea. But a little research shows that Nabatea’s borders extended to and overlapped with Idumea, in the regions of southern Judah and the Negev. In fact, Herod the Great’s father, Antipater, was Idumean, and his mother, Cypros, was Nabatean. I point this out because Paul was born a Roman citizen in the wealthy town of Tarsus, the playground of Antony and Cleopatra, with Antony being Herod’s sponsor at the time. All this begs the question, who were Paul’s highborn and ostensibly wealthy parents? If they and he were indeed Herodian, that might explain why Paul would have spent so much time in Arabia after his conversion.

PEORIA, ARIZONA

BEN WITHERINGTON RESPONDS:

I don’t think there is any reason to connect Paul with the Idumeans or the Herods. Paul’s family in Tarsus were leather workers. It is likely they obtained their Roman citizenship and wealth from service to the empire, namely the making of tents and other leather products for the Roman troops in Cilicia.

In the article “Paul of Arabia?” Ben Witherington describes the “Paul the basket case” scene as occurring after Paul’s time in Arabia, whereas the referenced Acts 9:25, read in context, clearly states this happened shortly after Paul’s conversion, due to his enthusiastically preaching the gospel for which he had been persecuting believers. Yes, I understand that the author of Acts edited events to smooth over the apparent conflict between Paul and the other apostles, hence some disconnects between Acts and Paul’s epistle to the Galatians. However, there is no evidence of that here.

GERMANTOWN, MARYLAND

BEN WITHERINGTON RESPONDS:

In the Acts account of the basket story, Luke does, indeed, compress things and doesn’t know about the trip to Arabia. The basket story, which Paul himself recounts in 2 Corinthians 11:32-33 and for which he is the primary source and Luke a secondary one, refers to King Aretas being after Paul through his agent in Damascus. This surely has to have happened after Paul did or tried to do something in Nabatean Arabia. What is not clear is whether Aretas already had control over Damascus when Paul was lowered in a basket down the wall.