Reviews

056

Byzantium: From Antiquity to the Renaissance

Thomas F. Mathews

(New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998) 176 pp., $18.95

Thomas F. Mathews begins his delightful survey of Byzantium’s history by emphasizing the links between this refined, elaborate civilization and its neighbors, both in time and place.

“Byzantium,” he writes, “constitutes a major piece of the puzzle of European history, and indeed of the history of the entire Mediterranean basin … As heir of the legal systems of Rome it supplied the model for the medieval state; as heir of the learning of Greece it served as elder mentor of Europe. Its military sealed the eastern borders of Europe from the expansion of Islam, while its economy linked Europe with the Near and Far East … [Byzantium’s] ivories and manuscripts circulated freely in the world of Islam, its enamels and silks were treasured in Paris, its icons were well known in Italy and Russia.”

Byzantine art, as Mathews promises to show his readers, “is surprisingly unlike the abstract and rigid stereotype in which it has sometimes been cast. It is personal and, in a sense, deeply subjective.” Indeed, nearly all of the book’s sumptuous images (122 in total) are tied to people: the patrons who commissioned the works, the artists who made them, and the mortals, saints, angels and divinities portrayed in them. Even emperors are humanized and brought down to earth—like Constantine, the eponymous founder of the Imperial City, which is the subject of Mathews’s first chapter. The next chapter, “Icons,” shifts immediately to the intimately personal realm, touching upon the complex mix of beliefs, hopes and doubts that first led the subjects of ancient Rome to embrace Christianity and inspired them to keep the faith thereafter.

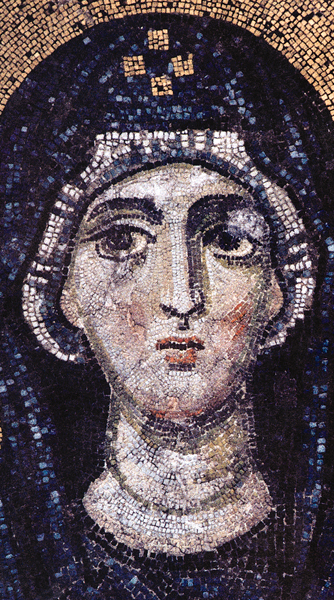

For Byzantine Christians, however, personal predilection often became political. In the early years of the eighth century, a violent debate erupted between the iconoclasts (image-smashers), biblical literalists who took to heart the Ten Commandments’ prohibition against graven images, and the iconodules (image-servants), who regarded sacred paintings as indispensable aids in meditation and prayer. The intensity of the passions aroused by this theological debate can be read negatively in an iconoclast’s hammer blows against a marble relief sculpture of Christ from a monastery in Istanbul, and positively in such iconodule efforts as a succession of haunting, big-eyed 058faces from the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mt. Sinai. (These icons are beneficiaries of the Romano-Egyptian pictorial tradition that produced the famous Fayum portraits, which becomes obvious as soon as Mathews points it out.) Fortunately, the iconodules prevailed. Mathews suggests that in significant measure the icons may have owed their survival to the persistent devotional habits of Byzantine women, from the Empress Theodora, who guaranteed their final rehabilitation in 843 (a manuscript painting shows Theodora’s mother, Theoktiste, instructing Theodora’s five daughters in the proper technique for adoring an icon of Christ), to the humble women who still keep Greek churches alive with flowers, lighted candles and crisp linens.

Mathews is particularly deft at showing how Byzantine art perpetuates the Greco-Roman artistic tradition, constantly transforming it but never, to his mind, forgetting classical art’s fundamental premise: “In contrast to Islam’s fascination with calligraphy and geometry, or China’s concern with the landscape environment of human life, Byzantine art took the human figure, in all its moods and poses, as its almost exclusive vehicle of expression, and in this it constitutes the essential bridge between antiquity and the Renaissance.” From this standpoint, he convincingly narrows the distance between a naked classical 059hero and a high Byzantine official swathed in ceremonial robes, between the Parthenon’s carefully sculpted exploration of well-proportioned anatomy and the depiction of a long-limbed saint in a glittering mosaic on the vault of a Christian church—and, by the same generous overview, between Byzantium and us.

The sheer material opulence of Byzantine art is irresistible, with its cloths of silk and precious metal, its gold and glass mosaics, its gems, the saturated color of its paints, the intricate works in gold, silver and ivory. Mathews’s publisher, Harry Abrams, has long made a specialty of lavish art books, and he has guaranteed that even this affordable paperback provides a splendid feast for the eyes. Happily, Mathews also gives ample treatment to a greater Byzantium that includes such hybrid works as the great cathedrals of Sicily; here, Byzantine artists worked for Norman kings in a setting in which Greek, Latin and Arabic were all spoken, and Latin was included beside Greek on mosaic inscriptions.

A final chapter (its content already hinted at by Mathews’s choice of title) shows cogently that Byzantine art was instrumental in shaping the art of the Italian Renaissance, with which it is frequently set at odds by art historians and critics. Viewing the Sicilian painter Antonello da Messina’s Virgin Annunciate (1473–1474), Mathews writes, “we sense a radically different kind of painting from the icons we have been looking at … Yet the composition to which the painting owes its strength is borrowed from an Italo-Byzantine icon of the thirteenth century—a half-length Mother of God with hands crossed on her breast. It is at this point, then, that the icon genre, which depended so heavily on portraiture in its origins, crosses back over to modern portraiture.”

It is no mean feat to compress a thousand years of human ingenuity into not quite two hundred pages. To do so with such breadth of perspective and evident pleasure is a rarer achievement still. The photograph of an elaborate Byzantine gold-and-ivory binding that is used as the cover for Byzantium encloses a small gem of a book.

060

The Legacy of Mesopotamia

Stephanie Dalley, ed.

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998) 226 pp., $105

Ancient Mesopotamia

Susan Pollock

(Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1999) 259 pp., hardback $49.95, paperback $17.95

Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia

Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat

(Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998) 307 pp., $45

Americans are in love with the past. A visit to your local bookstore will reveal how vast the history section has become, and the number of television channels devoted to history keeps multiplying. As a professional historian, I am not complaining.

There has been a recent proliferation of books on the ancient world directed to the general public, and this trend has also spread to Mesopotamia. The three books reviewed here are aimed at such an audience, yet their execution and success vary enormously.

The sheer price ($105!) of Stephanie Dalley’s The Legacy of Mesopotamia will keep it from the general public. Too bad, since the book is useful in pointing out the great reach of Mesopotamian culture. Dalley and her colleagues argue that Mesopotamian culture, which was predominant in the Near East when cuneiform writing was in use, could not simply have disappeared when that writing system died out. Mesopotamian influences on later European and Near Eastern traditions have been regularly ignored because disciplinary boundaries inhibit many scholars from taking a more catholic view. Interpreters of Hellenistic philosophy, for instance, do not know much of Mesopotamian culture and are unable to discern Mesopotamian influences on Greek thought.

The book presents an enormous wealth of data from literature, art, religion and science. It also examines the various cultures—Judeo-Christian, Greek, Roman, Parthian, Sassanian, early Islamic and Indian—that were inheritors of the Mesopotamian legacy. I sympathize with the authors’ concerns; much of the blame for our underestimating Mesopotamian influence on world culture results from two misconceived ideological notions: that a “Greek miracle” fertilized the roots of European civilization, and that a fundamental break in Near Eastern history occurred with the coming of Islam.

The authors raise some provocative questions. Anthropologists often debate whether certain similar cultural elements originated in one place and then spread by diffusion, or whether they were independently created in different places. Dalley and company clearly side with the diffusionists, yet some of the examples used to illustrate that point seem farfetched. For instance, they suggest that the Mesopotamian concept of a Tablet of Destinies (a divine text in which the destiny of mankind is recorded) lingered on in European literary traditions, where it emerged as the “Book of Fate” (a book recording human fate) referred to in Shakespeare’s Henry IV. This leap of faith stretches credulity. Despite the abundance of data presented, no clear analysis is given of what the major channels of transmission could have been or how particular cultural forms and customs were selected and modified.

Susan Pollock’s Ancient Mesopotamia traces early cultural developments in Mesopotamia (c. 5000–2100 B.C.). Largely focusing on prehistoric archaeological data, Pollack explores such elements as physical surroundings, settlement patterns and burial practices. The chapters are organized topically rather than chronologically. For instance, burial customs taking place in the fifth millennium are compared to those of the fourth and third millennia. Of the three books reviewed here, it the most successful, combining a great deal of anthropological research in a clearly focused whole. Well written and organized, Ancient Mesopotamia deals with important questions about the emergence of the earliest documented human civilization.

Another virtue of Pollack’s book is the author’s refusal to view history through rose-colored glasses. She points out that the great monuments we admire today were built with the back-breaking labor of the poor and subjected. Unfortunately, her editors vetoed the more telling, original title of the book, “Mesopotamia: The Eden that Never Was.”

Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat’s Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia proceeds from a 062geographical and historical survey of Mesopotamia to a selection of topics concerning daily life: writing, science, private and public activities, recreation, and so on. These are the usual subjects of popular reference books; in fact, the author passes on information gleaned from a number of earlier books, often themselves works of synthesis. The writing is unencumbered by jargon, yet oddly schoolmarmish, with one declarative sentence doggedly following another.

This book has the potential for a wide readership. It is likely to find its way into school and public libraries, considering its broader focus and the publisher’s familiarity with the popular market (of the three books under review here, only Daily Life in Mesopotamia is not published by a university press). So it is all the more troubling that the book is marred by numerous factual errors. Since it may introduce many readers to Mesopotamia by misinforming them, its mistakes are not only unfortunate but dangerous.

Authors of popular books on ancient Mesopotamia have a problem: The general reading public lacks the most basic familiarity with the sweep of Mesopotamian civilization. The burden of providing background information can be crushing. It also has the tendency to crowd out lively historical and cultural debates and to reduce the amount of controversial or innovative material. At worst, the result is tedium—a possibility that scares publishing houses and scholars away.

This wasn’t always so. Before World War II, archaeological discoveries in Mesopotamia were often spectacular events. Men like Leonard Woolley (renowned for his discoveries at Ur in the 1920s) could simultaneously present their finds to the scholarly world and the wider public. The challenge to authors and publishers today is to present the rich and exciting civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia in an accessible, yet intelligent, way. This means that scholars should take the work of synthesis more seriously, while realizing how important it is to raise interest in the field. It also means that publishers should be more confident about their readers’ intelligence and less timid about the publication of books that challenge the mind.

If material is lively and interesting, and if it is presented attractively, people will read it. In 1956, Samuel Noah Kramer published From the Tablets of Sumer. Twenty-five “Firsts” in Man’s Recorded History, a translation of 25 pieces of Sumerian literature familiar only to a few specialists. The book was not a commercial success; only 3,000 copies were sold. But then the French scholar Jean Bottéro intervened. He translated the work into French, pepped up its title, History Begins at Sumer, and gave it to a famous French publisher, Arthaud. The book sold 50,000 copies in one year, and the rights to the book were bought by 15 countries. Kramer became the voice of the Sumerians, and his colleagues never thought the less of him.

Byzantium: From Antiquity to the Renaissance

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.