Superheroes and the Bible

052

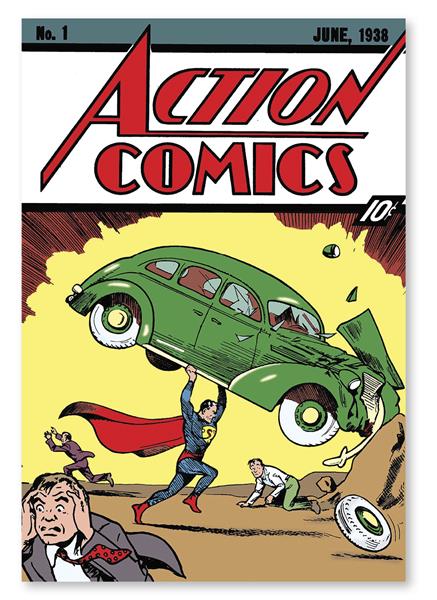

In 1938 a new all-american hero burst onto the scene armed with hope after the Great Depression and ready to take action when the U.S. entered World War II. The cover of Action Comics #1 depicted the “Man of Steel” wielding a car over his head, while people ran in terror. Superman came to the world to help the oppressed and needy. He was a “superhero,” the first of his kind. By World War II, 70 million Americans were reading his comics. As a response to public interest, the publishers readily created cartoons, radio shows, and eventually television programs. American culture was quickly saturated in Superman media.

What does Superman have to do with the Bible? Superman’s impact on global culture is so immense that it is almost impossible to read any hero without intertextually engaging with him. Superman is the urtext of the superhero genre. Every hero that comes after him, in a sense, is a response to his creation. Since we live in a post-Superman world, we as readers cannot retroactively read heroes as if he never existed. As a result, a circular intertext is created where Superman’s qualities (loosely based on biblical figures) is read back into the biblical text.1

This is evident in several ways. First, it is blatantly seen in how people make meaning of the Samson story. If we understand the Book of Judges within the narrative of the Deuteronomistic History or even reflecting the theology presented in the credo found throughout the narrative, the time of Judges descends into chaos, with the last major judge being Samson. However, outside of feminist scholarship, Samson is rarely read as a character that needs critique, despite his obvious, numerous flaws. This may be based partly on viewing Samson as a failed messiah or even a precursor to Jesus. When you read many commentaries devoted to Judges, Samson is 053 described as a military figure, a heroic savior, and even a superman.

Another way this is evident is through the scholarship regarding Superman’s religious background. Superman’s religion has been overly debated, with many scholars claiming parallels to—if not an outright—Jewish heritage. Reading Superman as Jewish often includes portrayals of him as a golem (an anthropomorphic being animated magically from inanimate matter), who is awakened by the “S” shield upon his chest. There are elements of the Moses narrative built into Superman’s origin. He is placed in a vessel (Superman: space ship; Moses: reed basket) as a child riskily sent away to a far-off land (Superman: planet; Moses: down the Nile) to live with a foreign people (Superman: alien humans; Moses: Egyptians) only to realize his true heritage and become a savior among them. There are also Superman parallels with Samson, the Hebrew Bible’s own strong man who has one true weakness or, dare I say, one true kryptonite?

The original creators of Superman, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were first-generation Americans whose parents were Jewish immigrants. There are too many obvious parallels to be coincidence. Other seemingly Jewish details within the Superman story, such as his Hebrew-sounding Kryptonian name Kal-El, even prompted Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels to denounce Superman and his creator publicly as Jewish in 1940.

On the other hand, what about a Christian Superman? This interpretation is largely due to his savior aspects, especially as portrayed in films. Richard Donner’s film Superman (1970) saw a heavenly father (Superman’s father, Jor-El) played by Marlon Brando speaking a Trinitarian monologue to a baby Kal-El that sounded so much like Jesus that Donner received death threats. Every Superman movie since has reinforced this imagery, including recent adaptations by Zack Snyder, Man of Steel (2013), and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016). Man of Steel depicted two fathers with Kevin Costner as the earthly father and Russell Crowe as the heavenly father. In the film, Superman is a god among humans, but his earthly parents teach him empathy and morality.

In Batman v Superman, Superman dies at the hands of the apocalyptic representation of evil named Doomsday. His broken body is lowered down to the ground, cradled by Lois Lane and flanked by Batman and Wonder Woman; two crosses are seen in the distance paralleling a super-Pieta—the famed subject of Christian sculpture depicting Mary holding a crucified Jesus. Of course, in the comic Death of Superman, Superman dies and eventually returns from the grave.

By arguing that Superman’s similarities to Moses or Jesus proves his religious leanings, we are projecting certain qualities on these figures. After Man of Steel, several articles were written asking whether Superman was the messiah of the modern age or even the savior that Americans desire. These texts were accompanied by theological interpretations of the movie complete with suggestions on how to apply these heroic principles from behind the pulpit. Some articles included long lists suggesting how to use Superman to read the Gospels.

Finally, the advent of comic book Bibles or graphic Bibles have long been influenced by the superhero genre established by the creation of Superman. Texts, such as the classic Picture Bible that has been reimagined by The Action Bible, highlight muscle-bound Samsons and Joshuas, proclaiming that real superheroes are found in the biblical text.

Superman has changed the way we make meaning from and in the Bible. For more than 80 years, Superman has deeply influenced generations who are reading and interpreting the Bible. Although Superman is not a Marvel superhero seen in the latest film Avengers: Endgame (2019), his influence is engrained throughout, and the millions of viewers will take their definition of a superhero, derived from Superman, and read it into the Bible.

In 938 a new all-american hero burst onto the scene armed with hope after the Great Depression and ready to take action when the U.S. entered World War II. The cover of Action Comics #1 depicted the “Man of Steel” wielding a car over his head, while people ran in terror. Superman came to the world to help the oppressed and needy. He was a “superhero,” the first of his kind. By World War II, 70 million Americans were reading his comics. As a response to public interest, the publishers readily created cartoons, radio shows, and eventually television programs. […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.