To see, or not to see, that is the question.

The British Museum has opened an innovative exhibition, Ancient Lives, New Discoveries, which focuses on eight individuals who lived, died and were mummified in ancient Egypt and Sudan. We are invited to look inside these individuals’ coffins and see the intricate layers of their burials—even to see their internal organs. Yet the mummies themselves—never having been unwrapped—remain completely intact.

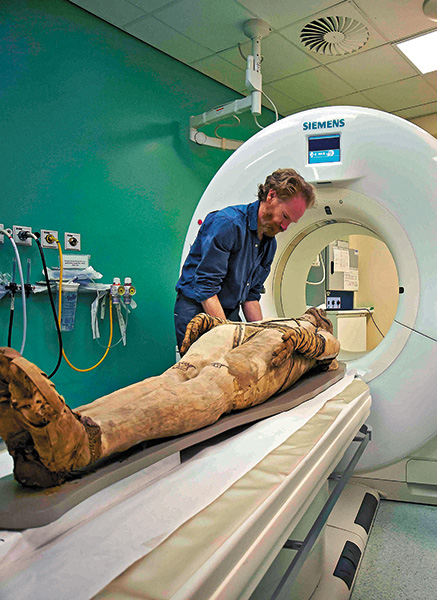

How is this possible? Using innovative technology, the British Museum is able to examine the bodies beneath the wrappings without ever damaging or disturbing the burials themselves.

Using modern technology to noninvasively study ancient mummies is not a new approach for the researchers and scientists of the British Museum. No mummy from their collection has been unwrapped in the past 200 years. In the 1960s, they performed a full x-ray survey of the mummies, which was followed by CT scans in the 1990s. Ancient Lives, New Discoveries is brought to life through a series of 3D visualizations, created from high-resolution data retrieved from new medical CT scans.

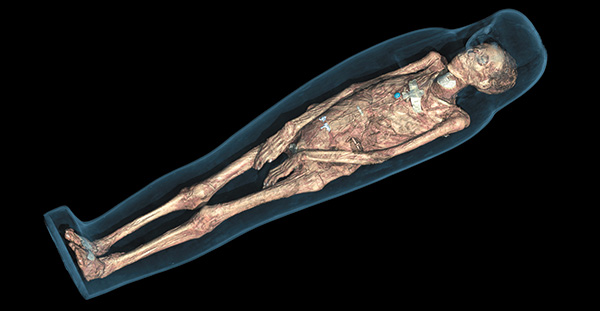

Projected on large screens next to each mummy, the visualizations illuminate details of these individuals’ lives and secrets of their mummification.

Tayesmutengebtiu (abbreviated Tamut), the daughter of a high-ranking priest, lived during the 22nd Dynasty (c. 900 B.C.) and likely served as a priestess in the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak in Thebes. She is called “Lady of the House” and “Chantress of Amun.” She was 5 feet 2 inches. The scans reveal that she suffered from atherosclerosis (plaque in her arteries) and died in her early thirties.

The 3D visualizations allow us to peer inside her decorated coffin and see how her body was preserved, her burial reflecting an elite level of mummification. Beneath the wrappings, amulets were arranged on her body, including a blue scarab on her heart, the winged scarab beetle god Khepri on her feet and metal covers on her toenails. Another visualization shows her skeleton, from which we are able to see that blue artificial eyes were placed in her eye sockets. Spells from the Book of the Dead could activate the amulets on her body and aid Tamut in the afterlife.

Another mummy, an adult male at least 35 years old, lived during the 26th Dynasty (c. 600 B.C.). His mummy was found in the Theban Necropolis. Although we do not know his name, the scans show that he stood at 5 feet 7 inches tall and suffered from painful dental abscesses, tooth decay and subsequent tooth loss. His brain and other internal organs were partially removed during mummification.

Representing more than 4,000 years of history, from the Predynastic period (c. 3500 B.C.) in Egypt to the Medieval period (c. 700 A.D.) in Sudan, the individuals selected for this exhibit show that mummification was not reserved for Pharaoh alone. They come from a variety of social levels—from the priestess Tamut to Tjayasetimu, a young temple singer who was mummified when she was just seven years old, from the unidentified man from the Theban Necropolis to Padiamenet, the chief doorkeeper of the temple of Ra.

But should mummies be on display at all?

Zoe Pilger, an art critic for The Independent, raises this question. While she commends the curators on their respectful treatment of the mummies, acknowledging the thought and care that went into the exhibit, she concludes that these mummies were never intended to be seen, and thus our fascination with them is intrusive:

Although Tamut’s coffin has not been disturbed, the act of exploring her insides with the aid of a CT scan nonetheless feels like trespassing. These bodies were not designed to be seen. There is a tyrannical tendency in Western culture to try to know everything—to decode, demystify, and disenchant even the most sacrosanct of secrets … [T]hese mummies are explored with scientific rigor and respect. Instead of revulsion, we are encouraged to feel a sense of shared humanity; they are dignified through the small detail of daily life—from the wigs they wore to the beer they drank. However, there is a feeling that they do not belong to us and should not be here.1

She raises a good point. While grave goods are common features of many exhibits, it gets a bit more complicated when human remains are put on display—rather than just their handicrafts.

Even though these mummies were not intended to be seen, they were meant to be remembered. Remembering and caring for the dead were central elements of belief in ancient Egypt and the rest of the ancient Near East. Being forgotten by your ancestors had serious consequences in the afterlife.

Some of these individuals (or their family members) went to great lengths to preserve their bodies and prepare themselves for the afterlife—to not be forgotten! Yes, the mummies were never meant to be removed from their original burials, but for various reasons they were (archaeology, looting in ancient and modern times, etc.).

This exhibit takes individuals who were forgotten by most of humanity and makes them known once more, and they do it in such a way that is nonintrusive, thereby preserving them for future generations. Through the exhibit, we get a glimpse of these individuals’ lives; we remember.

The exhibit runs through November 30 and is accompanied by the publication Ancient Lives, New Discoveries: Eight Mummies, Eight Stories by John H. Taylor and Daniel Antoine (London: British Museum Press, 2014).

To see, or not to see? We say, go see!

But what do you, our readers, have to say? As always, we are curious to hear your response!—M.S.